The Missouri River[1]Nicknamed Big Muddy, the Missouri River here should not be confused with Big Muddy Creek, which enters the Missouri River a few miles upstream from Culbertson, Montana. That’s the stream … Continue reading still contributes its tint, and something of its personality, to the Mississippi a few miles north of St. Louis. It curves around the point called Columbia Bottom with a flourish, nuzzles past two faintly discernible wing dams, embraces a small island with a seasonal slough, and yields itself to the Mississippi. Diesel-powered towboats drive long strings of barges back and forth between Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and some begin up the Missouri as far as Sioux City, Iowa. Cargoes include petroleum and related products, coal and coke, iron and steel, chemicals, grain, sand and gravel, and sulfur.

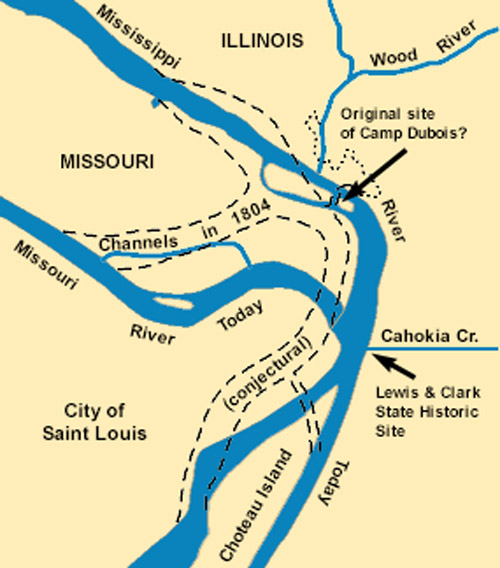

Dimly visible near the corner at lower right, almost opposite the debouchment of the Missouri, is the mouth of the Cahokia Creek Diversion Channel, where an interpretive center is under construction (beginning in the summer of 2001) at the Lewis and Clark State Historic Site.

Wood River, which lent its name to the Corps of Discovery’s cantonment of the winter of 1803-1804, is out of sight, somewhere at upper right.

Changes in Location

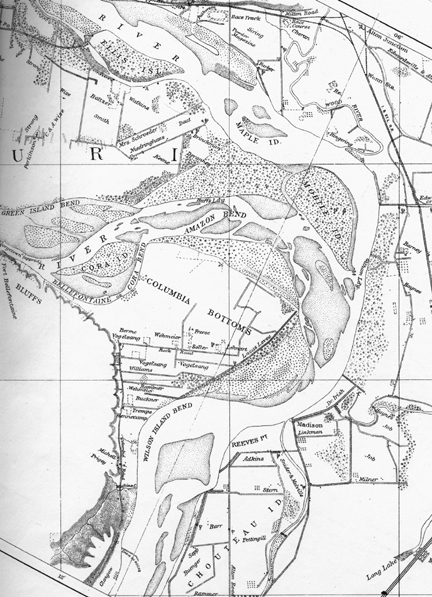

The Missouri River Commission (MRC) was established by Congress in about 1884 to direct a methodical development of control measures to assure a clear, hazard-free channel, with a consistent minimum depth, to facilitate the increasing river commerce. By that time, however, several transcontinental railroads had taken over the shipment of goods and people across the West, and in 1902 the MRC was abolished, leaving a legacy of eighty-three beautifully crafted maps of the Missouri from the Mississippi to the Three Forks, drawn from surveys made as early as 1879, and published in 1892. They now serve as important documents in the historiography of westward expansion, as well as for the study of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Gary Moulton has cited them frequently in his 13-volume edition of the Journals (see link at the bottom of this and all other pages in Discovering Lewis & Clark®).[2]The grid for the MRC maps measures 3.5 miles by 2.6 miles.

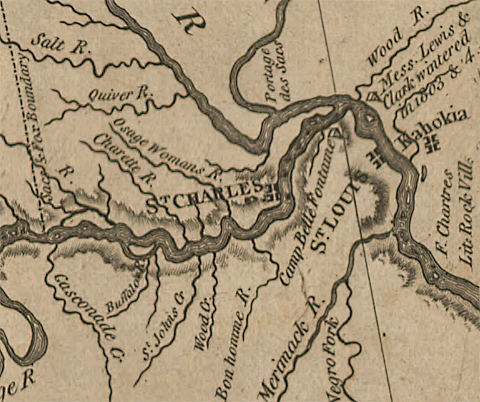

It is difficult to determine exactly how much, and how often, the confluence of the Missouri and the Mississippi Rivers changed during the nine decades since the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s departure from Camp Dubois. William Clark‘s 1814 map (below), which accompanied Nicholas Biddle‘s paraphrase of the two captains’ journals. Clark’s map was published at a smaller scale than the MRC maps, and was necessarily more generalized. However, a comparison of the two suggests that by the end of the 19th century the mouth of the Missouri had moved approximately 2½ miles south of its 1803—1804 location. The unnamed island on which Clark and the Corps of Discovery camped on the night of 14 May 1804, is impossible to identify in the MRC map, but Cora Island is still in existence. The settlement that had grown up in the southern part of Columbia Bottoms by 1890 is now a northern suburb of St. Louis called Spanish Lake.

Camp Belle Fontaine

Camp Belle Fontaine, the first U.S. fort west of the Mississippi was built in 1805 by General James Wilkinson, the first governor of Upper Louisiana Territory. It was established on the site of an old Spanish cantonment called Fort Bellefontaine, from the nearby spring (fontaine) of pure (belle) water. A “factory”—that is, a trading post—was built there too, to serve the Sac and Fox tribes (note the boundary line at left). The Corps of Discovery stopped at the camp on 22 September 1806, the day before the expedition ended at St. Louis. Captain Clark reported that they were “honored with a Salute of Guns and a harty welcome.”

Private George Shannon was hospitalized at Camp Belle Fontaine in the fall of 1807 after being wounded during a battle with the Arikaras while escorting Chief Sheheke back to his Mandan village. The trading post was closed in 1808, and part of its inventory was transferred to Fort Osage, some 100 miles farther up the Missouri. After the Missouri River flooded the Columbia Bottoms in the spring of 1810, the camp was rebuilt on the bluff to the southwest, consisting of thirty log buildings plus blockhouses and palisades. It was the departure point for Zebulon Pike‘s expeditions up the Mississippi in 1805 and to the southwest in 1806, and for Stephen Long’s expedition to the Rocky Mountains in 1819. It was abandoned in 1826, when the military quarters were moved to Jefferson Barracks, south of St. Louis.[3]Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804—1806, 8 vols. (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1905), 5:392n. St. Louis County Government, “Fort Belle … Continue reading

The site is now Fort Belle Fontaine Park, under the administration of the government of St. Louis County.

Winter Camp at Wood River (Camp Dubois) is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The site, near Hartford, Illinois, is managed as Lewis and Clark State Historic Site and is open to the public.

Fort Belle Fontaine is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. Located about twenty miles north of St. Louis on the Missouri River, this historic site is now a a St. Louis County Park with several buildings and a stone staircase from its current location on a bluff down to the original location on the river.

Notes

| ↑1 | Nicknamed Big Muddy, the Missouri River here should not be confused with Big Muddy Creek, which enters the Missouri River a few miles upstream from Culbertson, Montana. That’s the stream “of a yellowish Colour” which, on 29 April 1805, Clark named “Martha’s.” or “Marthey’s river in honor to the Selebrated M.F”—though nothing else is known about her. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The grid for the MRC maps measures 3.5 miles by 2.6 miles. |

| ↑3 | Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804—1806, 8 vols. (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1905), 5:392n. St. Louis County Government, “Fort Belle Fontaine Park,” http://www.stlouisco.com/ParksandRecreation/ParkPages/FortBelleFontaine. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.