“The commander requires intelligence

in order to effectively execute . . . engagements

and other missions across the full spectrum

of operations. Intelligence assists the commander

in visualizing his battlespace, organizing his forces,

and controlling operations to achieve the desired

tactical objectives or end-state. Intelligence

supports force protection . . . by alerting

the commander to emerging threats

and assisting in securing operations.”

One of the basic responsibilities of any military unit in the field is, and has always been, reconnaissance—the gathering of intelligence. Useful information. Among its numerous achievements, the “Corps of volunteers for North Western Discovery”[1]The title “corps of volunteers for North Western Discovery,” now commonly shortened to “Corps of Discovery,” appeared in the journals for the first time on 26 August 1804, … Continue reading was in many respects the most successful reconnaissance operation in the early history of the U.S. military.

Menaces on the Horizon

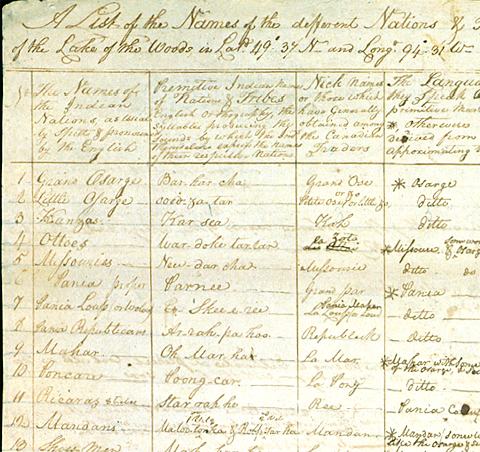

Estimate of Eastern Indians (detail)

To see labels, point to the image.

American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

In Clark’s spreadsheet there are 14 more columns to the right of this detail, and 40 more lines below it. The overall dimensions of the seven sheets of letter paper pasted together are approximately 35″ by 28″.[2]Moulton, Journals, 3:386-450.

In view of its sheer size, the bulk of the territory the Lewis and Clark expedition transected—from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, and from somewhere up north toward Canada, south to wherever the boundary with New Spain was—had been securely under the legal ownership of the United States government during the months since the consummation of the Louisiana Purchase on 30 December 1804. Even the region beyond the Rockies to the Pacific was nominally U.S. property, since Robert Gray had left the name of his ship on its river in 1792, and a few months later Captain George Vancouver had acknowledged that priority. Nevertheless, there were persistent international challenges to the integrity of the newly acquired territory as well as to the de facto U.S. claim to the Oregon territory. Authorities in New Spain, militarily impotent, were gripped with paranoia fueled by letters from none other than an American, General of the Army James Wilkinson, and feared that the American expedition had targeted their legendary gold and silver mines, as well as Santa Fe, their northern trading post with Indians. In response, between the summer of 1804 and the winter of 1806, Governor Fernando de Chacón of New Mexico dispatched a total of four military detachments of soldiers into American territory to either drive the explorers back down the Missouri, or else imprison them. Fortunately, none of those missions was successful.

The overriding threat, however, loomed along the northern boundary of Louisiana, although no one knew precisely where that was. It came to a head in 1802 with the publication of Alexander Mackenzie‘s Voyages from Montreal, in which the Scotsman recounted his crossing of North America from the St. Lawrence River to Bella Coola Bay on the Pacific Coast, leading a party of only nine men. Voyages concluded with a challenge to his own country, Great Britain, to be more aggressive about developing a transcontinental trade route. By that means, he maintained, “the entire command of the fur trade of North America might be obtained, from latitude 48. North to the pole, except that portion of it which the Russians have in the Pacific.” Moreover, Mackenzie declared:

to this may be added the fishing in both seas, and the markets of the four quarters of the globe. Such would be the field for commercial enterprise, and incalculable would be the produce of it, when supported by the operations of that credit and capital which Great Britain so pre-eminently possesses. Then would this country begin to be remunerated for the expenses it has sustained in discovering and surveying the coast of the Pacific Ocean, which is at present left to American adventurers, who without regularity or capital, or the desire of conciliating future confidence, look altogether to the interest of the moment. They, therefore, collect all the skins they can procure, and in any manner that suits them, and having exchanged them at Canton for the produce of China, return to their own country. Such adventurers . . . would instantly disappear from before a well-regulated trade.[3]Alexander Mackenzie, Voyages from Montreal: On the River St. Laurence [sic], Through the Continent of North America to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans, in the Years 1789 and 1793; With a Preliminary … Continue reading

Smarting from the affront, President Jefferson snatched up the gauntlet, and after some feverish deliberation, on 18 January 1803, took up the matter with Congress. Duly emphasizing commercial objectives that the legislators were prepared to deal with—”The interests of commerce place the principal object within the constitutional powers and care of Congress”—he proposed that “an intelligent officer with ten or twelve chosen men, might explore the whole line, even to the Western ocean.” By the 20th of June his orders were ready for Captain Lewis’s command.

Regulating Indian Trade

Simply put, the keys to American hegemony throughout greater Louisiana were in the hands of the Indian nations. Whichever empire—Spain, Great Britain, or the United States—could interface with the Indian nations through carefully regulated trade would control the territory. Jefferson had a simple two-part plan. The first step, he explained to Congress, would be “to encourage them to abandon hunting.” That, he assumed, would relieve them of dependence upon “the extensive forests necessary in the hunting life,” which would then obviously become useless to the Indians, who would “see the advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms, & of increasing their domestic comforts.” Second, “to multiply trading houses among them, & place within their reach those things which will contribute more to their domestic comfort than the possession of extensive, but uncultivated wilds. “Experience & reflection will develope to them the wisdom of exchanging what they can spare & we want, for what we can spare and they want.”

It was a timely topic. The Act for Establishing Trading Houses with the Indian Tribes, first passed in 1796, was up for renewal again during the 1803 session. Congress approved it, with additions, two months later. Each trading house was to be operated by a bonded agent of the U.S. government, who was authorized to purchase only skins and furs, pay for them with designated trade goods, and in turn to sell them at a minimum of six public auctions per year. The proceeds, of course, were to accrue to the government. Meanwhile, traders and factors from the North West Fur Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company continued to ply the lower and middle Missouri, the Red River of the North, and the upper Mississippi, while New Spain’s contracted traders tried to keep their grip on Indian trade to the south.

Questions to Answer

Questions. The entire saga of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was inspired by questions. Jefferson’s questions, Caspar Wistar‘s questions; Benjamin Rush‘s, Dearborn’s, and others, all leading lights in the President’s intellectual circle, all thinking along the same lines. The result became the large, powerful spring in a windup, perpetual-motion machine. Rush, for instance, gave Lewis a list of twenty-one questions to direct toward Indian informants concerning “Physical history and medicine,” “Morals,” and “Religion.” (See Questions for Indians.) Andrew Ellicott, Robert Patterson, and Albert Gallatin contributed their questions and recommendations. The two men selected to share command of the undertaking possessed commensurate, interlocking capacities. They inquired into all quarters of the geographical and natural world, and pried into the region’s human communities, as far as the diligent pursuit of their journey admitted. Their conclusions weren’t always right, in hindsight, but the information was conscientiously sought. (Think of Lewis’s ultimate reaction to the puzzling Unaccountable ‘Artillery’ of the Rockies: “I have no doubt but if I had leasure I could find from whence it issued.”)

The enterprise had two overriding objectives. The first was to find, follow, and map “with great pains and accuracy,” “the most direct and practicable [elsewhere, ‘convenient’] water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.” The second was tied to the final clause of the first. “The commerce which may be carried on with the people inhabiting the line you will pursue, renders a knolege of those people important. You will therefore endeavor to make yourself acquainted, as far as diligent pursuit of your journey shall admit, with the names of the nations & their numbers.”[4]Jackson, Letters, 1:62

Sometime in 1804, Clark assembled a list of “Inquiries relitive to the Indians of Louisiana,” based on Jefferson’s list of indicators plus Benjamin Rush’s ethnomedical interests, with others offered by Caspar Wistar and Benjamin Smith Barton.[5]Ibid., 1:161n. The list ranged from “Physical History and Medicine” to “Relative to Morrals,” religion, “Traditions or National History,” “Agriculture and Domestic economy,” “Fishing & Hunting,” amusements, “Clothing Dress & Orniments,” and “Customs & Manners Generally.”[6]Ibid., 1:157-61. Of course, the explorers and their men observed Indian people constantly and intently, often writing meticulously detailed descriptions in their daily diaries, but the Estimate of Eastern Indians had a different slant.

Estimate of the Eastern Indians

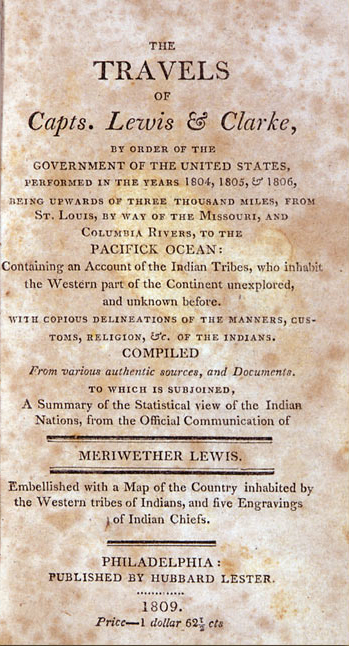

Title page of the first of the apocrypha—referring to “writings of questionable authorship or authenticity”—purporting to be accounts of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The appearance of nine such publications, almost identical to one another, within thirty years beginning in 1809, attests to their popularity, and to the public’s indifference to authenticity.

The bountiful store of intelligence Lewis and Clark accumulated held far-reaching implications for the future of the new nation, both scientifically and politically. Many of its details, however, such as the natural history discoveries, didn’t fully come to light until a century later, when the original journals were edited and published by Reuben Gold Thwaites.[7]Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition 1804-1806, in Seven Volumes and an Atlas (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1905). The completion of an accurate map of their route based on coordinates derived from the explorers’ celestial observations, which was another of Jefferson’s primary objectives, was not realized during his lifetime.[8]In 1816, at age 73, Jefferson was still trying to find someone who could work out the data for longitudes that Lewis had accumulated from the more than 100 points of observation he recorded along the … Continue reading

However, the expedition did have one major outcome that was made available to the public well before the expedition was over. That was the “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,”[9]Moulton, Journals, 3:386-450. The reference to “Eastern Indians” sounds confusing today. Clark meant the eastern part of Louisiana Territory. His own description of the chart read: … Continue reading which Lewis and Clark compiled during the winter of 1804-05 and sent back on the barge that left Fort Mandan for St. Louis on 7 April 1805. Retitled “A Statistical View of the Indian Nations Inhabiting the Territory of Louisiana and the Countries Adjacent to its Northern and Western Boundaries,” it officially became a public document on 19 February 1806, when Jefferson made it part of his annual Report to Congress, seven months before the Corps got back. At the request of Congress, a thousand copies were printed the following month. Within another few months it was reprinted numerous times in whole or in part, in the popular press. It was reprinted from the government document published in Natchez, Mississippi, in March 1806, as the first part of Discoveries Made in Exploring the Missouri, Red River and Washita by Captains Lewis and Clark, Doctor Sibley, and William Dunbar, and Compiled by Thomas Jefferson.[10]Erickson, Jeremy Skinner and Paul Merchant, eds., Jefferson’s Western Explorations (Spokane, Washington: Arthur H. Clark, 2004). Excerpted from Dunbar’s journal are 32 “Historical … Continue reading Between 1809 and 1840 the narrative paragraphs about each of the tribes, based on War Department guidelines, also appeared in seven separate books known now as “apocrypha” or “clandestine” journals, which otherwise were somewhat of the quality of today’s supermarket tabloids.[11]The Travels of Capts. Lewis & Clarke, by Order of the Government of the United States, Performed in the Years 1804, 1805, & 1806, . . . (Philadelphia: Hubbard Lester, 1809), 154-178. The … Continue reading

The captains sent two maps along with their draft of the Estimate. One consisted of 29 manuscript pages charting in detail the course of the Missouri River as far as the Knife River villages. The other was “A Map of part of the Continent of North America, . . . Compiled from the Authorities of the best informed travellers by M: Lewis. . . . The Country West of Fort Mandan . . . laid down principally from Indian information.” In early July 1805, Jefferson forwarded both maps to Nicholas King for copying and publication, intending to distribute them to Congress along with the “Statistical View of the Indian Nations.” For some reason, never explained and still unknown, they were not published, and therefore were not circulated. Three manuscript copies of Clark’s larger map do still exist, however. They include the locations of many of the Indian tribes the captains listed east of Fort Mandan, and several to the west of it.

The second one was Clark’s 1814 map of the “Track Across the Western Portion of North America from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean.” It materialized eight years after the expedition as a feature of Nicholas Biddle‘s paraphrase of the captains’ journals, thereafter serving until the middle of the 19th century as the authoritative chart of the entire region, and the baseline for subsequent maps. It also showed the locations of many Indian tribes and bands from the Mississippi to the Pacific Coast.

Most valuable of all would have been the fourteen or more Indian vocabularies that Lewis painstakingly collected. Jefferson had provided him with forms listing 315 English words for which he was to seek Indian equivalents. Each list would have been extremely useful to government agents, fur traders, and future scientists, had they not all been destroyed accidentally in 1809 by “an irreparable misfortune.”[12]Jackson, Letters, 2:465; Ronda, Lewis and Clark Among the Indians, Bicentennial edition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 126.

Intelligence Gathering

At Fort Clatsop during the winter of 1804–05, in compliance with the President’s orders, the captains developed a “List of the Names of the different Nations & Tribes of Indians Inhabiting the Countrey on the Missourie and its Waters.” It was a prodigious task, involving the reiteration of 19 questions to Indian informants and Euro-American traders concerning some 72 tribes known or believed to reside within the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase, including 19 southern tribes, that were characterized by from 4 to 7 points. While they discussed many of the tribes and bands in fuller detail elsewhere in the journals, a few were mentioned only in this chart, which is commonly referred to as the “Estimate of the Eastern Indians”—meaning east of the Rocky Mountains.

The captains carried out their research through a two-way chain of interpreters—English-to-French-to-Indian language, or perhaps English-to-Drouillard’s-signing-to-Indian language. Sometimes the linguistic chain would have to be extended to five links each way. Other communication problems complicated the process. Some of these were obvious, such as the differences between Indian and Euro-American conventions for defining time and distance. Others were more likely obscure, such as personal, political, or cultural prejudices based on long-established friendships or enmities, which could have stimulated boastful pride in relating friendly associations, or delight in sharing gossip. On the other hand, the seeming impertinence of the interrogators’ queries might have aroused suspicion of their motives, or disgust over their impertinence. In most instances there was no way to cross-check the answers they believed they heard. (For a modern example: in some parts of the West, it is still considered bad manners to ask a farmer or rancher how many acres are in his spread.) They met only a few of the tabulated tribes face-to-face, so most of the information had to come second- or third-hand from willing, congenial traders, or from trustworthy Indian authorities.[13]James Ronda, Lewis & Clark Among the Indians, 1984; Bicentennial edition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 114-15. At Fort Mandan, the captains were suspicious of the real motives … Continue reading

The young United States had institutionalized the collection of intelligence with the Second Continental Congress’s creation of the Committee of Secret Correspondence for the purpose, as George Washington expressed it, of obtaining “Intelligence of the Enemy’s situation & numbers.”[14]Intelligence in the War of Independence, http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/warindep/frames.html. Accessed 28 December 2006. However, although Lewis and Clark fully expected to encounter armed resistance en route up the lower Missouri, if not all along their route, they were determined to triumph by reasonable diplomacy, demonstrations of the power of civilized technology, and the promise of free trade, but not by threats of punitive retaliation. There would be no need of secrecy, no call for clandestine operations. Those ciphers (See Jefferson-Lewis Cryptology.) Jefferson had prepared for Lewis had been intended to keep sensitive details from the administration’s more powerful enemies among the Federalists. After the consummation of the Louisiana Purchase, justifications for the expedition were no longer important—although Lewis continued to worry about it, perhaps until the very end of the journey—and secrecy was unnecessary.

The result was, as James Ronda has described it, “a kind of statistical geography,” which proved to be “a limited but practical document for government agents and fur traders.”[15]Ronda, LCAI 126. James Ronda, “Lewis & Clark and Enlightenment Ethnography,” in William F Willingham and Leonoor Swets Ingraham, eds., Enlightenment Science in the Pacific Northwest: … Continue reading To any other nation, at any other time, it would have qualified as “intelligence”—useful information.

Demographics

First on the list was the tribe’s name, “as usally Spelt and pronounc’d” in English, and second, their own name for themselves. These were written with great care, and as much precision as their informant’s diction plus their own aural acuity would allow. As Nicholas Biddle noted during one of his conversations with Clark in 1810, “In taking vocabularies great object was to make every letter sound.”[16]During his consultations with William Clark in the spring of 1810, in preparation for writing his paraphrase of the two captains’ journals. Jackson, Letters, 1:62. No doubt it took considerable practice to get the process refined. Reading now those many hyphenated Indian names in the journals, one can imagine the interviewer repeating a name over and over, slower and slower, rehearsing sounds for which no conventional English symbols exist, and making on-the-fly compromises.[17]Abbreviated examples of the treatments of just one vowel were provided in the printed document, essentially as follows:– over a, denotes that a sounds as in caught, taught, &c.â … Continue reading We can see him searching both the interviewee’s and the interpreter’s expressions at every step as he speaks and writes, until he recognizes approval. One can hear him finally reading back the name—fluently, without the hyphens—to the smiles and nods of all concerned. One can imagine that Clark was probably the better of the two captains at this, accustomed as he was to listening to sounds of words to divine their spelling.

Third, the nicknames by which contemporary Canadian traders knew them; fourth, the language family or dialect they spoke. In practical terms, these four questions were census elements of the overall demographic objective of the Estimate. From a strictly scientific perspective, however, interest in Indian languages, specifically comparative linguistics, on the part of Jefferson, Benjamin Smith Barton, and others among their circle both in the U.S. and in Europe was part of the ongoing debate between deists and strict Biblical Christians concerning the ages of the human races.[18]John C. Greene, American Science in the Age of Jefferson (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1984), 376-408. Jefferson had already hypothesized that the American aborigines might be the oldest on earth, “perhaps not less than many people give to the age of the earth.”[19]Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 19 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950-[1997]), 10:240.

More demographics followed: The number of villages comprising each nation, plus the number of tents or lodges in each, with the total number of “souls” per tribe, which came to approximately 65,000, not including ten nations for whom no numbers were given, other than an occasional “verry noumerous.” The “Darcotar or Sioux nation” was shown to consist of twelve major bands.

Military Strength

From the standpoint of military intelligence, however, the critical question was “G,” the “Number of Warriours” in each tribe or nation. That total, to which the numerous tribes of the Sioux nation contributed the largest number, came to 17,660, not including the fighting forces of the eleven tribes—some of them marked “very noumerous”—for which the captains were unable to obtain specific estimates. In contrast, owing to Jefferson’s conservative economics of national defense, all the U.S. could field in 1802 was a standing army of about 3,300 men, already widely deployed among a number of isolated outposts (See Lewis’s Report on Army Officers.) such as those along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. That disparity confirmed the wisdom of Jefferson’s insistence on peaceful means to earn the loyalties of the Western nations.

In the spring of 1810 he told Nicholas Biddle “Calculate one warrior in the rovers of the plains [for every] four women & children. On both sides of Rock Mountains & in the mountains—below Columbia falls not so numerous say 3-1/2.”[20]Jackson, Letters, 2:503.

Commercial Potential

Commercial parameters were taken up next. “The names of the Christian Nations or the Companies with whome they Maintain their Commerce and Traffick” was followed by “The places at which the Traffick is usially Carried on.” The northern tribes, such as the Mandans, Hidatsas, Blackfeet, and Assiniboines dealt with the British through the North West and Hudson’s Bay companies; those to the south of the Missouri River, including the Pawnees, Crows, and Shoshones, dealt with traders licensed by the government of New Spain. The places of business were varied in situation and character. Many were said to trade at their respective villages; some traveled to Indian hubs at the confluences of rivers such as the mouth of the Knife at the Missouri; others traded at moving venues such as hunting camps; a few were centered on established American trading posts at St. Louis, or British houses on the St. Peters (Minnesota) River, the Qu’apelle, or the Assiniboine River in Canada, and at other rendezvous points at the mouths or forks of certain rivers. The Shoshones were reported to have traveled to “New Mexico” to carry on trade with Spanish merchants.

The next two questions followed logically upon the previous two: “k. The estimated Amount of Merchindize in Dollars at the St. Louis . . . prices for their Anual Consumption,” and “l. The estimated amount of their returns, in Dollars, at the St. Louis . . . prices.” Here the captains’ experiences in dealings with tribes east of the Mississippi must have served them well. Beyond that, their discussions with Canadian traders at Fort Mandan must have been particularly informative. No doubt it was Lewis who wrote the following explanation of their calculations:

The sums stated under . . . “L” are the amounts of merchandise annual furnished the several nations of Indians, including all incidental expenses of transportation, &c. incurred by the merchants which generally averages about one third of the whole amount. The merchandize is estimated at an advance of 125 per cent. on the sterling cost.[21]Sterling here refers to the value of the dollar as established by the Mint Act of 1792, based on specific weights and purities of silver and gold. In practice, monetary exchange values during the … Continue reading It appears to me that the amount of merchandise which the Indians have been in the habit of receiving annually, is the best standard by which to regulate the quantities necessary for them in the first instance; they will always consume as much merchandize as they can pay for, and those with whom a regular trade has been carried on have generally received that quantity.

The amount of their returns stated under and opposite “M” are estimated by the peltry standard of St. Louis, which is 40 cents per pound for deer skins.

According to this formula, for example, the captains estimated that the Grand Osage Indians would annually consume $15,000 worth of merchandise, and would provide $20,000 worth of peltries and hides. The standard of value the captains cited, $0.40 per pound of deer skins, would have been roughly equal to $6.64 in 2004, according to the Consumer Price Index.[22]Samuel H. Williamson, “What is its Relative Value?” Economic History Services, 14 December 2005, http://eh.net/hmit/compare/ Accessed 18 February 2006. Lewis added a remark indicating that this category of their reconnaissance was conditional: “These establishments are not mentioned as being thought important at present in a governmental point of view.”

Clark’s Planned Forts

During the winter of 1804-05 Clark acquired enough information about the Indian population as well as the geography of the lower Missouri and upper Mississippi River basins to project a series of 12 trading establishments to serve those two regions. It was the logical extension of the answers to question “O” in the Estimate. Clark listed “The Number of Officers & Men for to protect the Indian trade and Keep the Savages in peace with the U.S. and each other,” even though he had not yet seen most of the locations. One at the mouth of the “Rochejone” (Yellowstone River) would be manned by a company of 63 men: 1 Indian agent, 1 captain, 1 lieutenant, 1 ensign, 1 sergeant major, 4 interpreters, 3 sergeants, 3 corporals, 3 musicians (drummers and fifers) and 45 privates. A “fort” at the Great Falls of the Missouri would require only 38 men: 1 lieutenant, 1 sergeant major, 2 interpreters, 2 sergeants, 1 corporal, 1 musician (drummer) and 30 privates.[23]Moulton, Journals, 3:479-80. Fifteen tribes, Clark calculated, would be served at the mouth of the Yellowstone; four would trade at the Falls.

By the third of August, however, Clark had changed his mind on one point, abandoning the idea of positioning one trading center at the Falls of the Missouri in favor of the mouth of Clark’s Fork of the Yellowstone. To an establishment there, he was convinced:

the Shoshones both within and West of the Rocky Mountains would willingly resort for the purposes of trade as they would in a great measure be reli[e]ved from the fear of being attacked by their enimies the blackfoot Indians and Minnetares of fort de Prarie [Atsinas], which would most probably happen were they to visit any establishment which could be conveniently formed on the Missouri. I have no doubt but the same regard to personal safety would also induce many numerous nations inhabiting the Columbia and Lewis’s river West of the mountains to visit this establishment in preference to that at the entrance of Maria’s river, particularly during the first years of those Western establishments. the Crow Indians, Paunch Indians Castahanah’s and others East of the mountains and south of this place would also visit this establishment; it may therefore be looked to as one of the most important establishments of the western fur trade. at the entrance of Clark’s fork there is a sufficiency of timber to support an establishment, an advantage that no position possesses from thence to the Rocky Mountains.

Within but a few years that proposal also proved to have been a serious error in judgment. Manuel Lisa, of the St. Louis Fur Company, and one of the first St. Louis entrepreneurs to benefit from the jawbone journals repeated by the men of the Corps, particularly the stories of the abundance of beaver on the Yellowstone River. In 1807 Lisa built a short-lived trading post at the mouth of the Big Horn, Fort Raymond, and moved his traplines to the Three Forks of the Missouri in 1809, but was driven out by the Blackfeet within a few months. The highlight of all the futile early efforts to take beaver from the middle Yellowstone and the Three Forks was John Colter‘s historic 250-mile dash for his life from Blackfeet warriors. Clark himself saw to the building of the first trading post on his own list, Fort Osage near present-day Sibley, Missouri, in 1808; marginally successful in the long run, it was in operation only until 1827.

Commodities

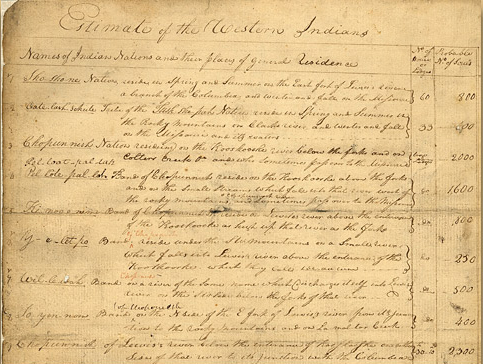

Estimate of Western Indians

Image courtesy of the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, and Valerie-Anne Lutz, Assistant Manuscripts Librarian and Registrar.

At Fort Clatsop during the winter of 1806, the captains compiled an “Estimate of the Western Indians” occupying the region between the Rockies and the Pacific Coast. It listed only the names of 83 tribes and bands, along with their places of residence at that time, the numbers of houses or lodges and the probable number of “souls” in each. The absence of Indian informants as intelligent and forthcoming as Sheheke and Posecopsahe (Black Cat), or traders as widely experienced as Hugh Heney, James Mackay, or Pierre Chouteau, who were available to them at Kaskaskia, St. Louis and Fort Mandan, undoubtedly discouraged the captains from trying to construct as elaborate a table as they had produced for their Estimate of Eastern Indians.

Biddle included a narrative version of only the Western estimate in his 1814 paraphrase of the captains’ journals, perhaps because the Eastern one had already been widely circulated. Clark’s final map (1814), showed the areas occupied by 30 of the tribes and bands from the Western estimate.

Items “N” and “O” on the list of queries covered the kinds of “peltries & Robes” which the tribes had supplied to traders, and the “defferant kinds of Pelteres, Furs, Robes Meat Greece & Horses” which each could supply. The next question, “P,” asked for “The place at which it would be mutually advantageous to form the principal establishment in order to Supply the Several nations with Merchindize.” Questions “Q” and “R” addressed intertribal issues: “The Names of the Nations with whome they are at War,” and “The names of the Nations with whome they maintain a friendly alliance, or with whome they may be united by intercourse or marriage.” The last item, “S,” consisted of the captains’ responses to questions that had been addressed to Secretary of War Dearborn in the original manuscript. Each was a narrative summary, probably written by Lewis, of the tribe’s status in terms of up to nine points. Each began with a capsule characterization of the tribe, from the most admirable (the Mandans: “the most friendly, well disposed Indians inhabiting the Missouri. . . . brave, humane and hospitable.”) to the least (the Sioux: “These are the vilest miscreants of the savage race, and must ever remain the pirates of the Missouri, until such measures are pursued, by our government, as will make them feel a dependence on its will for their supply of merchandise.”)

Jefferson submitted the “Estimate of Eastern Indians” to Congress with his annual report on February 19, 1806, summarizing it in his address as “a statistical view, procured & forwarded by [Lewis], of the Indian nations inhabiting the territory of Louisiana & the countries adjacent to it’s Northern & Western borders of their commerce, & of other interesting circumstances respecting them.”[24]Jackson, Letters, 2:298-300.

In addition to the “Estimate of Eastern Indians,” the 1806 Message from the President opened with the President’s Message, followed by Jefferson’s “Extract of a letter from Captain Meriwether Lewis to the President of the United States, dated Fort Mandan, April 17th, 1805.” Then came the “Estimate of Eastern Indians.” The rest of the report consisted of documents representing two other expeditions that Jefferson had instigated, of portions of the Louisiana Purchase. One was the three-month-long exploration of the Oushita River by William Dunbar and George Hunter that began on 16 October 1804, and concluded with their return to Natchez, Mississippi, on 26 January 1805. The other consisted of reports from Dr. John Sibley, whom Jefferson had appointed as Indian Agent in the Southern Red River country. (See also on this site The Freeman-Custis Expedition.)

Without accompanying maps to lend geographical relevance to their contents, the Estimates of Eastern and Western Indians qualified as purely “literary” documents. As such, they at least satisfied the public’s thirst for news of the expedition. At most, they provided serious and attentive Americans with ostensibly useful information that was impressive in its scope, serious in its method and purpose, and fascinating in its details about the human textures and dimensions of the land beyond the Mississippi.

The author gratefully recognizes contributions to this article by Brigadier General Hal Stearns, Montana National Guard.

Notes

| ↑1 | The title “corps of volunteers for North Western Discovery,” now commonly shortened to “Corps of Discovery,” appeared in the journals for the first time on 26 August 1804, when Lewis recorded Patrick Gass‘s selection to replace the late Sgt. Charles Floyd. “North Western” referred then to the entire quarter of the continent northwest of St. Louis, or, as sometimes described, “the interior parts of North America” watered by the Missouri River. It did not include the region west of the Rockies and north of California that now comprises the states of Washington and Oregon, which is now commonly called “the Northwest.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Moulton, Journals, 3:386-450. |

| ↑3 | Alexander Mackenzie, Voyages from Montreal: On the River St. Laurence [sic], Through the Continent of North America to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans, in the Years 1789 and 1793; With a Preliminary Account of the Rise, Progress, and Present State of the Fur Trade of That Country (London: T. Cadell, 1801), 411. |

| ↑4 | Jackson, Letters, 1:62 |

| ↑5 | Ibid., 1:161n. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., 1:157-61. |

| ↑7 | Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition 1804-1806, in Seven Volumes and an Atlas (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1905). |

| ↑8 | In 1816, at age 73, Jefferson was still trying to find someone who could work out the data for longitudes that Lewis had accumulated from the more than 100 points of observation he recorded along the route, which would be used to draft an accurate map of the expedition’s journey. From those astronomical observations alone, he wrote to his friend José Corrèa da Serra in 1816, “can be obtained the correct geography of the country, which was the main object of the expedition.” Jackson, Letters, 2:618. In fact, ever since the mid-1970s, Professor Robert N. Bergantino, of the Montana School of Mines and Geology in Butte, has been studying Lewis’s data and solving the equations according to procedures Robert Patterson laid out in a manual for Lewis in 1803. Dr. Bergantino’s discoveries are at last coming to light on this website. See Celestial Observations. |

| ↑9 | Moulton, Journals, 3:386-450. The reference to “Eastern Indians” sounds confusing today. Clark meant the eastern part of Louisiana Territory. His own description of the chart read: “A List of the Names of the different Nations & Tribes of Indians Inhabiting the Countrey on the Missourie and its Waters, and West of the Mississipi (above the Missouri),” etc. Ibid., 388. |

| ↑10 | Erickson, Jeremy Skinner and Paul Merchant, eds., Jefferson’s Western Explorations (Spokane, Washington: Arthur H. Clark, 2004). Excerpted from Dunbar’s journal are 32 “Historical Sketches of the Several Indian Tribes in Louisiana, South of the Arkansa River, and Between the Mississippi and River Grand.” Ibid., 159-178. |

| ↑11 | The Travels of Capts. Lewis & Clarke, by Order of the Government of the United States, Performed in the Years 1804, 1805, & 1806, . . . (Philadelphia: Hubbard Lester, 1809), 154-178. The one cited here, attributed to the pseudonymous “Hubbard Lester,” was published in Philadelphia in 1809; another was issued in London the same year. Subsequent knock-offs of the “original” fake came out in 1811 (two in German), 1812 (one in German, two in English), 1813, and 1840. Each consisted partly of genuine reprints of public documents from and to President Jefferson, including reports from Lewis and Clark, Sibley, and Dunbar, pertaining to various unrelated subjects, plus plagiarisms—mostly unattributed—from other explorations such as those of Jonathan Carver (1778) and Alexander Mackenzie (1792), and shamelessly fictitious filler. Several of the books were illustrated with five execrable engravings, including a bare-breasted “Sioux Queen.” Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976), 33-39. Stephen Dow Beckham, et al., The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Bibliography and Essays (Portland, Oregon: Lewis and Clark College, 2003), 121-143. |

| ↑12 | Jackson, Letters, 2:465; Ronda, Lewis and Clark Among the Indians, Bicentennial edition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 126. |

| ↑13 | James Ronda, Lewis & Clark Among the Indians, 1984; Bicentennial edition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 114-15. At Fort Mandan, the captains were suspicious of the real motives of François-Antoine Larocque, of the British North West Company, who wanted to join the American expedition. See Larocque at Fort Mandan. |

| ↑14 | Intelligence in the War of Independence, http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/warindep/frames.html. Accessed 28 December 2006. |

| ↑15 | Ronda, LCAI 126. James Ronda, “Lewis & Clark and Enlightenment Ethnography,” in William F Willingham and Leonoor Swets Ingraham, eds., Enlightenment Science in the Pacific Northwest: The Lewis and Clark Expedition (Portland, Oregon: Lewis and Clark College, 1984), 5-17. |

| ↑16 | During his consultations with William Clark in the spring of 1810, in preparation for writing his paraphrase of the two captains’ journals. Jackson, Letters, 1:62. |

| ↑17 | Abbreviated examples of the treatments of just one vowel were provided in the printed document, essentially as follows: – over a, denotes that a sounds as in caught, taught, &c. â denotes that it sounds as in dart, part, &c. a, without notation has its primitive sound as in ray, hay, &c. except only when it is followed by r or w, in which case it sounds as â. , set underneath denotes a small pause, the word being divided by it into two parts. These diacritical marks were used infrequently in the Estimate; they appear more often in the captains’ daily journals. |

| ↑18 | John C. Greene, American Science in the Age of Jefferson (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1984), 376-408. |

| ↑19 | Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 19 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950-[1997]), 10:240. |

| ↑20 | Jackson, Letters, 2:503. |

| ↑21 | Sterling here refers to the value of the dollar as established by the Mint Act of 1792, based on specific weights and purities of silver and gold. In practice, monetary exchange values during the early 19th century still varied somewhat from one region or market area to another. Thus the wisdom of specifying “on the sterling cost.” |

| ↑22 | Samuel H. Williamson, “What is its Relative Value?” Economic History Services, 14 December 2005, http://eh.net/hmit/compare/ Accessed 18 February 2006. |

| ↑23 | Moulton, Journals, 3:479-80. |

| ↑24 | Jackson, Letters, 2:298-300. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.