Dividing Forces

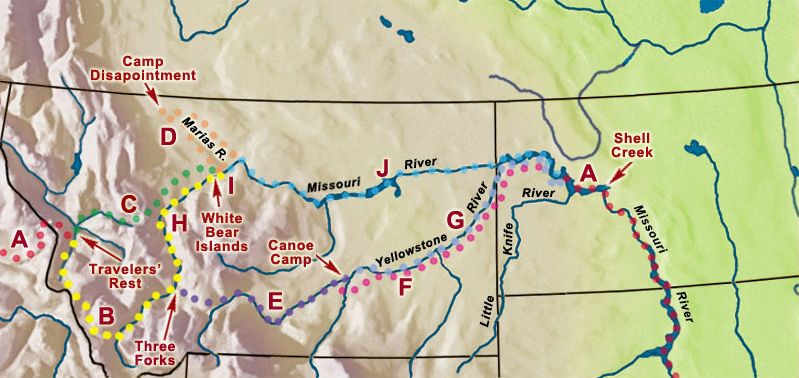

The map and chart below shows the 33 members dividing forces at Travelers’ Rest. They illustrate the complexity of the tactical plan Lewis and Clark conceived at Fort Clatsop and revised en route according to the exigencies of the moment. It attests to the military discipline and “A-Team” spirit the Corps of Discovery had learned from the countless challenges they had already met, solved and survived.

© 2000 VIAs Inc.

Map Key

A—Full company (33), to Travelers’ Rest and from the mouth of the Yellowstone

B—Clark, to Three Forks of the Missouri (23)

C—Lewis, to White Bear Islands (10)

D—Lewis, to Camp Disappointment (4)

J—Lewis to Shell Creek (19)

E—Clark, to Canoe Camp (13)

F—Pryor, to Little Knife River (4)

G—Clark, to Little Knife River (9)

H—Ordway, to White Bear Islands (10)

I—Gass & Ordway to Marias River (16)

On 24 July 1806, the day Clark departed from his “canoe camp” on the Yellowstone, Lewis was waiting out the weather at Camp Disappointment on Cut Bank Creek. They were three hundred miles apart.

Upon leaving Travelers’ Rest on the morning of 3 July 1806, they had expected to rendezvous at the mouth of the Yellowstone about 5 August 1806. Clark was two days early; Lewis was two days late. They finally met again on 12 August 1806, a few miles below the mouth of the Little Knife River, about 142 miles downriver from the Yellowstone.

Lewis’s Explanation

Excitement and relief, plus the unaccustomed pleasure of resting in real beds, indoors at the home of Pierre Chouteau, conspired to make sleep elude the two captains on the night of Tuesday, 23 September 1806, after their arrival in St. Louis. More than likely they made use of their wakefulness to begin drafting letters to their families, friends, and President Jefferson. Nevertheless, they rose early, Clark reported, and “Commencd wrighting,” for they had to get their mail across the Mississippi River and into the postmaster’s hands at Cahokia for dispatch at noon. One of Clark’s first letters was to his brother, George Rogers Clark.[1]More recent research shows the letter was to Clark’s brother Jonathan. See James J. Holmberg, ed. Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark (New Haven: Yale University Press, … Continue reading Knowing that this letter, like most important ones in that day, possibly would be read en route, and certainly would be widely circulated after delivery, Clark allowed Lewis to apply his comparatively more literate writing style to the task.

They summarized the expedition in terms of matters that would be of the most general interest, such as distances, navigability of rivers, and the long portage across the Rockies, and answered a question that was bound to be asked by someone, sometime: “Wouldn’t it have been easier and quicker to use that shortcut on the way west, too?”

In our outward bound voyage we ascended to the foot of the rapids below the great falls of the Missouri where we arived on 14 June 1805. Not haveing met with any of the nativs of the Rocky Mountains we were of course ignorant of the passes by land which existed through those mountains to the Columbia river, and had we even known the rout we were destitute of horses which would have been indispensably necessary to enable us to transport the requisit quantity of amunition and other stores to ensure the success of the remaining part of our voyage down the Columbia; we therefore deturmined to navigate the Missouri as far as it was practicable, or unless we met with some of the nativs from whom we could obtain horses and information of the Country.

A Growing Divide

Here is the way this all came about.

Back in the fall of 1803 Lewis had written to his commander-in-chief that he might send Clark up the Mississippi a ways, and himself would do some exploring up the Kansas River toward Santa Fe. Jefferson fired back a stern reprimand: “The object of your mission is single, the direct water communication from sea to sea formed by the bed of the Missouri & perhaps the Oregon [Columbia]. By having Mr. Clarke with you we consider the expedition double manned, & therefore the less liable to failure, for which reason neither of you should be exposed to risques by going off of your line.”[2]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, 1783-1854 (2nd ed., 2 vols., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:234.

Lewis prudently let the matter drop. The following April, before leaving Fort Mandan, he wrote to the President again: “On our return we shal probably pass down the yellow stone river, which from Indian information, waters one of the fairest portions of this continent.”[3]Ibid., 1:137. Sheheke (Big White), a chief of the Mandans, had provided Clark with abundant details about the river and the land it “watered.” Obviously it would be a mistake not to explore it. Lewis gave no hint that he and Clark were thinking of splitting the Corps into two detachments, either because they had not yet envisioned it themselves, or because they had decided to keep their options open. But by the time the Corps arrived at the Marias River on 1 June 1805, division was definitely in the plan. They cached some supplies and hid one of the two pirogues there, and left more supplies and the other pirogue at the Falls of the Missouri. They would have to split up on the return trip.

The captains gradually grew accustomed to the idea. From Fort Mandan westward the exigencies of the explorative process more and more required them to separate now and then, and leapfrog up the river, one on land, the other with the flotilla.[4]Arlen J. Large, “The Leapfrogging Captains,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 8, No. 3 (July 1982), 4-5. Lewis forged ahead as they approached the mouth of the Yellowstone. He and Clark explored the Missouri and Marias Rivers separately for several days. They collaborated at a distance during the long portage around the Falls. One or the other reconnoitered ahead of the main party as they proceeded up Jefferson’s River, and also when they arrived at the mouth of the Columbia. Circumstances were priming them for the month-long separation they had in mind for their return.

At Fort Mandan during the winter of 1804-05 Clark drew a new map of the Northwest that reflected what he had learned about the Rocky Mountains since the beginning of the expedition.[5]Discussed in Moulton, 1:9, and Map 32b. When the Corps left their winter quarters on 7 April 1805 and proceeded up the Missouri, Clark knew there was a mainline Indian road that crossed the Rockies and terminated in the territory of the “Flat head” Indians—those he later learned to call the “Pierced Nose” or Chopunnish Indians. (That terminus as illustrated on King’s map conflicts with the captains’ later understanding that war parties from the Plains did not enter the mountains west of Travelers’ Rest.) He and Lewis chose not to question their local informants for any more details at the time. Their primary objective was to find a water route through the Northwest, and to do that they would have to trace the Missouri River to a source that would be nearest to a source of the Columbia. However, the idea of exploring the alternative land route may have taken root in their minds before they left Fort Mandan.

Splitting Ways

With their arrival at Travelers’ Rest on 9 September 1805, the geographical interface of the Rockies with the rivers that “watered” them became clearer. Toby immediately pointed out to Lewis that:

not very distant from where we then were [“Clark’s River,” the Bitterroot today] formed a junction with a stream nearly as large as itself which took it’s rise in the mountains near the Missouri to the East of us and passed through an extensive valley generally open prarie which forms an excellent pass to the Missouri. the point of the Missouri where this Indian pass intersects it, is about 30 miles above the gates of the rocky mountain, or the place where the valley of the Missouri first widens into an extensive plain after entering the rockey mountains.

Furthermore, Toby said that the distance from where they were to the Missouri could be covered in four days’ travel. That “excellent pass” undoubtedly paralleled Interstate 90 for 70 miles eastward to the Little Blackfoot River, thence 55 miles over the Continental Divide and past today’s Helena, Montana, to the Missouri River somewhere below the famous Gates of the Mountains, a total of 145 miles. Adding 100 miles overland (120 by river) from there to White Bear Islands would have made the total distance of 240 miles.

Toward the end of May 1806, Clark sketched a map from information provided by “Sundery Indians of the Chopunnish Nation together.”[6]Moulton, 7:316. It featured the main trunk trail from the Clearwater River over K’useyneiskit (the “buffalo road”) to Travelers’ Rest, thence up the Cokahlah rishkit (Big Blackfoot) River, reaching the Missouri between Dearborn’s River and Medicine (Sun) River.

Roads to the Missouri

At Long Camp on 4 June 1806, Lewis invited chiefs Broken Arm, Cut Nose, and Hohots Ilppilp to accompany the Corps to the Missouri. The three Nez Perce politely declined. Furthermore, wrote Lewis, “they gave us no positive answer to a request which we made, that two or three of their young men should accompany me to the falls of the Missouri and there wait my return from the upper part of Maria’s river where it was probable I should meet with some of the bands of the Minnetares from Fort de Prarie; that in such case I should indeavor to bring about a good understanding between those indians and themselves.” Obviously, by then the captains had thought the whole plan through. At Travelers’ Rest they would divide the Corps not only into two detachments, but would later dispatch details as small as three or four men.

Leading the larger detachment, Clark would return to Fortunate Camp, dig up the supplies and materials they had cached there, and proceed to the Three Forks. From Fortunate Camp, Sergeant Ordway and nine men would paddle the six canoes down to White Bear Islands to begin the portage, while Clark took the remainder of his unit up the Gallatin River and over the Bridger Mountains to the Big Bend of the Yellowstone River. There, according to the plan, he would carve dugout canoes to carry most of the rest, including Charbonneau, Sacagawea, and Jean Baptiste—by now nicknamed Pomp—down to the Missouri where they expected to meet Lewis and his detachment about the first of August. While the canoes were being readied, Sergeant Pryor and two other men would begin driving the 50-horse remuda on ahead to the Knife River Villages, leave some of the mounts there and take the rest northward to Fort Assiniboine as payment to trader Hugh Heney for negotiating with the Lakota Sioux for a tribal envoy or two to accompany the captains back to Washington City. Clark’s assignment was an ambitious and dangerous scheme to undertake without Indian guides to pilot them through the unfamiliar territory. His best hope would be to meet some Crow Indians, whom he expected would be friendly and helpful. Charbonneau could serve as his interpreter.

Lewis and his dog, with nine men and 17 horses, plus five Indian guides to accompany them as far as the Falls of the Missouri, would then take five of his men on an even more important and hazardous mission. He and six volunteers would explore “Maria’s” River to find out whether any of its sources began as far north as Latitude 49 degrees, 37 minutes. If they found one, that would serve to draw the line between the U.S. and Canada from the Great Lakes to the Rockies that had been fixed in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which would make it easier for American authorities to exclude British traders from the profitable markets on the Middle Missouri.

It all was destined not to turn out that way, but that was the plan. So far, the overriding outcome of the expedition had been the discovery that 300 years’ worth of speculation and exploration had come down to one simple reality: There never was a riverine Northwest Passage across the continent after all. This intricate and dangerous plan that the two captains had cooked up between them was their “consurted” effort to achieve such salutary results from their journey that the American people would forget the old fantasy.

Notes

| ↑1 | More recent research shows the letter was to Clark’s brother Jonathan. See James J. Holmberg, ed. Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 106–07.—ed. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, 1783-1854 (2nd ed., 2 vols., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:234. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., 1:137. |

| ↑4 | Arlen J. Large, “The Leapfrogging Captains,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 8, No. 3 (July 1982), 4-5. |

| ↑5 | Discussed in Moulton, 1:9, and Map 32b. |

| ↑6 | Moulton, 7:316. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.