Fusil, Fuzee, Fusee

Captains Lewis and Clark frequently referred to the “fusils” “fusees,” or “fuzees” in the hands of Indians.[1]Noah Webster, in his Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806), Americanized the noun into the phonetically literal form, fusee. Near Fort Pierre, South Dakota, on 26 September 1804, Clark noted that some of the Indians were “badly armed with fuseis.” The word evolved from a Latin vernacular word, focus, meaning “fire.” By the 17th century it came to denote a light musket or firelock.[2]The word firelock at first (in the 17th century) denoted the mechanism by which sparks were produced by flint struck by a piece of steel, in order to ignite some priming powder in the pan of a gun. … Continue reading

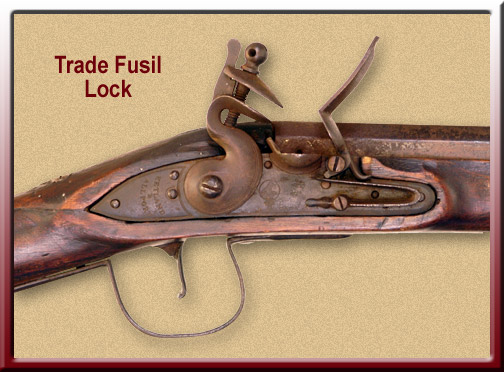

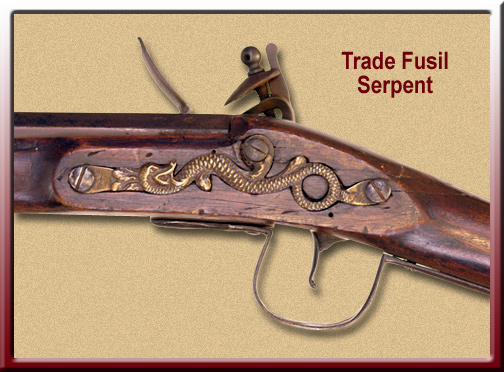

From the seventeenth century on, French fur traders and later the British supplied their Indian clients with smoothbore muskets both as gifts and in trade for pelts. By the late 1700s the style of these guns had standardized into a form the Indians came to prefer. Those flintlock muskets, which were universally called by their French name “fusils,” generally were lighter and more slender than contemporary military muskets, were of .60 caliber (24 gauge).[3]Gauge is a standard of measurement applied to shotgun barrels. It represents the number of lead balls exactly the same diameter as the inside of the barrel that will add up to one pound in weight. They had an oversize trigger guard, a flat brass butt plate attached with nails, and a side plate of a coiled sea serpent. It was long thought that the extra-large trigger guard was made to accommodate a gloved hand. But recent inspection of original documents from the Hudson’s Bay Company reveals a request sent to gunmakers in England in 1740 stating the Indians demanded large trigger guards because they liked to use the first two fingers of the hand to pull the trigger. Apparently that grip was more stable when firing from horseback than just the index finger.

On 15 January 1806, Captain Lewis commented on the armament of Chinookan Peoples, incidentally revealing the quality of their arms, and their tendency to abuse them (cp. “Thunder Gun“).

their guns are usually of an inferior quality being oald refuse American & brittish Musquits which have been repared for this trade. they are invariably in bad order; they apear not to have been long enouh accustomed to fire arms to understand the management of them. They have no rifles, . . . obtain their ammunition from the traders; when they happen to have no ball or shot, they substitute gravel or peices of potmettal, and are insensible of the damage done thereby to their guns.

Even though the Hudson’s Bay Company and other traders passed tens of thousands of trade fusils to the Indians, the guns are quite scarce today. In the hands of the Indians, the guns suffered extensive use and abuse. When they were beyond repair, they were broken down for scrap. The buttplates were typically used as hide scrapers, and the barrels were flattened at the muzzle to serve as digging implements

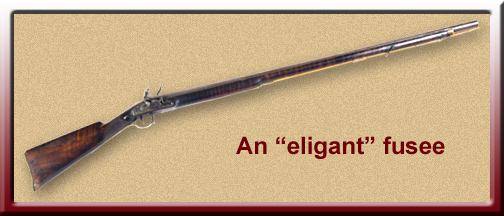

Charbonneau’s “eligant fusee”

Captain Clark, Sacagawea, Pomp and Toussaint Charbonneau were almost swept away in a ravine that drained into the Missouri just above the highest of the Great Falls of the Missouri, by a flash flood on 29 June 1805. Clark reported that, along with other items, they lost Charbonneau’s “eligant fusee.” A month later, on 30 August 1805, Clark gives his own fusee—likewise “eligant,” no doubt—to one of the men so that the latter can trade his musket for a horse.

A fusil could be a simple lightweight firelock intended for the Indian trade, or it could be very well constructed, have fine-figured wood, engraving on the metal parts, enrichment with silver inlays, excellent sights, and the newest refinements on the flintlock mechanism—or anything in between. Apparently, Charbonneau’s elegant fusil was considerably superior to the common trade fusil. We can imagine the excitable French-Canadian’s distress over the loss of so fine a piece of design and craftsmanship.

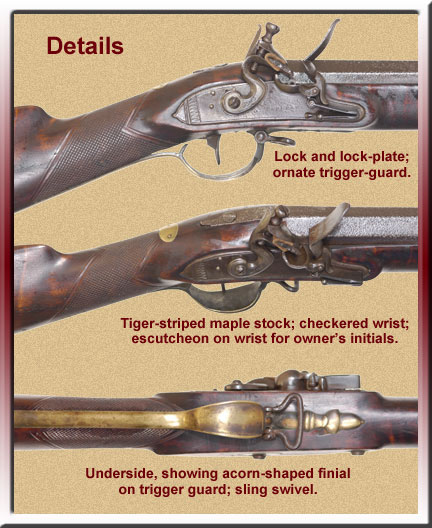

The specimen illustrated here has a full stock of tiger-striped maple with brass fittings called “furniture.” The trigger guard has an acorn-shaped finial. The wrist has fine checkering and a silver escutcheon on top. The barrel is 40″ long, .67 caliber, and half octagon, half round in profile. As with all fusils, the bore is smooth for the sake of versatility. It could be loaded with a solid ball to be used on large game, buckshot for medium-sized game, and bird shot for waterfowl and smaller birds.

Details

Photo by Michael Carrick

Features:

- Ornate trigger plate

- Stock made from tiger-striped maple

- Checkered carving on stock wrist

- Escutcheon on wrist for owner’s initials

- Acorn-shaped finial on trigger guard

Notes

| ↑1 | Noah Webster, in his Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806), Americanized the noun into the phonetically literal form, fusee. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The word firelock at first (in the 17th century) denoted the mechanism by which sparks were produced by flint struck by a piece of steel, in order to ignite some priming powder in the pan of a gun. That mechanism soon came to be called a flint-lock, and that term soon came to denote the weapon as a whole. |

| ↑3 | Gauge is a standard of measurement applied to shotgun barrels. It represents the number of lead balls exactly the same diameter as the inside of the barrel that will add up to one pound in weight. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.