The Versatile Musket

About half of the enlisted men in the permanent party of the expedition were chosen by Captain Meriwether Lewis from among regular Army troops stationed in the general vicinity of St. Louis. Since Lewis originally planned on a smaller group, he had only fifteen rifles specially prepared for the expedition at Harpers Ferry armory in Virginia in 1803. Therefore, these additional enlisted men were expected to bring with them their standard-issue arms—the US. Model 1795 musket and bayonet.

Congress passed a bill in 1794 to establish three or four national armories. The first was in Springfield, Massachusetts, where the first “United States Musket” was produced in 1795. The national armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, produced its first musket in 1800, and continued to turn them out until 1814. The musket illustrated above was made at Harpers Ferry in 1801.

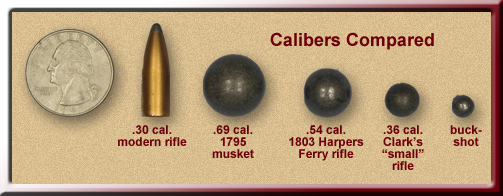

The model 1795 muskets had a .69 caliber, 44-1/2″ barrel, an overall length of 59″ and a weight of about 9-1/2 lbs. When hunting big game such as deer, elk, or buffalo, a .69 caliber round lead ball would be used. Because the barrel was smoothbore—that is, had no rifling grooves to spin the bullet and enhance accuracy—it could be used with birdshot pellets in the same manner as today’s shotgun.

On 10 May 1804, in preparation for their departure from Camp Dubois on the fourteenth, Clark ordered “every man to have 100 Balls for ther Rifles & 2 lb. of Buck Shot for those with mussquets & F[uzees].”

Bayonets are mentioned only twice in the journals. On 6 August 1805, when the party struck camp opposite the mouth of the Big Hole River in southwestern Montana, one of the men left his bayonet behind; Clark and his contingent found it there the following year. Also, both Clark and John Ordway wrote in mid-June of 1806 that two men had made fishing gigs by attaching bayonets to poles.

Army Rifles of 1800

In a letter dated 14 March 1803, Henry Dearborn, Secretary of War, instructed the superintendent of the Harpers Ferry Armory, Joseph Perkins, to “make such arms & Iron work, as requested by Captain Meriwether Lewis.”

Lewis ordered fifteen rifles to be made, and on 8 July he wrote to President Jefferson, “Yesterday I shot my guns and examined the several articles which had been manufactured for me at this place; they appear to be well executed.” In addition to the rifles, he ordered fifteen slings and replacement parts.

Firearm historians are not in agreement over exactly which model Captain Lewis picked up at Harpers Ferry. The candidates are 1) U.S. Model 1803 rifle; 2) 1792-94 contract rifles; or 3) modified 1792-94 contract rifles. All three are shown here, and we will discuss them in turn.

Harpers Ferry Model 1803

This is the rifle that is illustrated in most books about the expedition. Up until the late 1990s there was little disagreement that a prototype or precursor to the standard Model 1803 military rifle was Lewis’s gun, and that it would have looked just like the production-run rifles. The first issue of this rifle had a 33-inch barrel, seven grooves, and one turn in 48 inches. It was nominally a .54 caliber bore shooting a round ball of .525 inch.[1]See Flayderman’s Guide to Antique American Firearms, 8th ed. (Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications, 2001).

Careful inspection of archival records shows, however, that the Model 1803 rifle was still in the development stage after Lewis had picked up his fifteen rifles and was on his way to Pittsburgh to pick up the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’). The first of the Model 1803 rifles was finished in October 1803, and by that time, Lewis was meeting up with Clark at the Falls of the Ohio River.

1792-94 Contract Rifle

As a result of the disastrous defeat of General Arthur St. Claire in November 1791 by Indians in Ohio, the Army decided to raise three additional regiments.

These regiments would include companies of riflemen, and Lewis and Clark would get their first military experience in those rifle companies. In order to arm the rifle companies, the government contracted with several gunmakers in the vicinity of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to produce serviceable rifles. In all, over 3,000 rifles were ordered on the 1792 and 1794 contracts.

Archival records show that over 300 of these rifles were at the Harpers Ferry Armory at the time Meriwether Lewis was ordering his supplies. Some historians argue that Lewis would have picked out fifteen of the best examples of these rifles—why fabricate something new when there were over 300 rifles to choose from? Both he and Clark would have been familiar with these rifles from their service on the frontier under General Anthony Wayne.

The 1792-94 contract rifles were full-stocked rifles with a 42″ octagon barrel of .49 caliber. They had brass furniture and a brass patchbox. Lewis had swivels installed and ordered fifteen slings.

1792-94 Contract Short Rifle

Other historians agree that Lewis would have taken fifteen of the contract rifles but believe that Lewis ordered modifications. Lewis knew that much time was going to be spent in canoes, and that the hunters would be shooting buffalo, elk, bears and other large game.

So, for the convenience of handling the rifles in close quarters, he would have had the 42″ barrels shortened by six or eight inches and had the bore enlarged from .49 caliber to .54 caliber. Lewis does mention “short” rifles several places in the Journals.

If Lewis had ordered the full stocks to be cut back to half stocks, the forward portion of the barrel turned round to reduce weight, and a metal rib installed under the barrel to protect the ramrod, the result would have been a prototype of the U.S. Model 1803 rifle which appeared soon after Lewis left the Armory.

No one knows for certain if Lewis 1) designed a rifle to be newly constructed in the form which later became the U.S. Model 1803 rifle; 2) took 15 standard 1792–1794 contract rifles; or 3) selected 15 contract rifles and had them shortened and modified to suit his needs for the expedition.

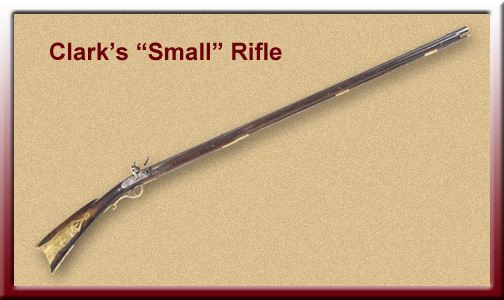

Clark’s Small Rifle

William Clark carried his personal hunting rifle on the expedition. It would have been a style known today as a “Kentucky Rifle.” He frequently referred to it in his journal as his “small rifle.” This has caused some confusion because in the collection of the Missouri Historical Society there is a rifle the provenance of which connects it with the Clark family. It was made by a man named John Small, of Vincennes, on the Wabash River. Was this the firelock Clark called his “small rifle”?

John Small, who had settled in Vincennes about 1780, had served with William Clark‘s older brother, the famous George Rogers Clark, which established his connection with the Clark family. In addition to being a gunsmith, Small was the first sheriff of Vincennes. He served in the first Indiana Territory Legislature, and was a Colonel in the Indiana Militia. He died in 1823.

Compared with the minutely detailed descriptions the captains often wrote concerning their discoveries of places, people, flora, and fauna, specifics about the survival tools they used every day were rarely mentioned, and even then are found in an incidental context. For example, in his journal entry for 10 December 1805, Clark described a little comic scenario that unfolded on the Necanicum River near today’s Seaside, Oregon.

one of the Indians [Clatsops] pointed to a flock of Brant [a kind of goose] Sitting in the creek at Short distance below and requested me to Shute one, I walked down with my Small rifle and killed two at about 40 yds distance, on my return to the houses two Small ducks Set at about 30 Steps from me the Indians pointed at the ducks they were near together, I Shot at the ducks and accidently Shot the head of one off, this Duck . . . was Carried to the house and every man Came around examined the Duck looked at the gun the Size of the ball which was 100 to the pound and Said in their own language, Clouch Musket, wake, com ma-tax Musket which is, a good Musket do not under Stand this kind of Musket &c.

The caliber of a ball at 1/100th of a pound is about .36, or 36 hundredths of an inch in diameter—the size of a pea. Most of the other rifles the Corps carried, including the 15 Lewis had requisitioned from the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, ranged from .47 to .54 caliber, and the 1795 muskets some of the men carried would have been .69 caliber. By comparison, Clark’s “Small rifle” was unquestionably a small rifle.

Another experience recounted in the journals emphasizes that Clark’s favorite rifle had too small a bore to make it reliable for big game shooting. On 8 August 1804 (from the diary of John Ordway): “the Capt. [Clark] Shot Several times at one [elk] but his rifle carried a Small Ball, took 2 men went to hunt it and he did not Git it.” Again, on 24 August 1804, Clark mentioned that in addition to killing two bull elk that evening he wounded two others, but could not track them by blood drops because “my ball was So [too] Small to bleed them well.”

Still, we can’t be certain. Was his “small rifle” so-called just because of its relatively small bore? Or because it was made by John Small? Or both?

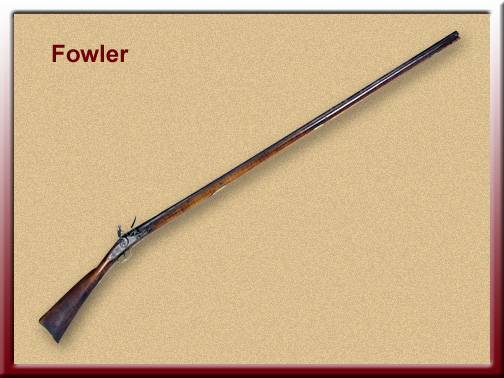

Fowling Piece

In the 1800’s, a “fowler” was a smoothbore gun that today we would call a shotgun. These fowling pieces were intended for birding and wildfowl shooting. Generally, they were long slender guns. The specimen illustrated is over five feet long and has a 50 inch barrel of about 20 gauge.

The average shotgun today has a 28″ or 30″ barrel. Long barrels were considered necessary to give the indifferent black powder of the day more time to burn to full strength and hence, it was thought, shoot farther and harder.

Clark and Lewis made note of more than 130 species of birds during the course of the expedition. Most of these were shot, examined, measured and described.

Lewis did not mention his “fowler” in the journals. Not until 1807 do we learn that he had a specific bird-shooting gun, when he documented the financial records of the expedition and asked for reimbursement for “one Uniform Laced Coat, one silver Epaulet, one Dirk & belt, one hanger & belt, one pistol & one fowling piece, all private property, given in exchange for Canoe, Horses &c. for public service during the expedition.”[2]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters and Documents of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1783-1837, 2nd ed., 2 vols (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:428.

Gunsmithing on the Trail

Gun barrels of that era were made of softer metal than today’s, and Clark’s “small rifle” also suffered from that common fault, as we learn from the following account. On 7 April 1806, as the Corps prepared to ascend the Cascades of the Columbia and anticipated close encounters with the Indians from there on, the captains ordered the men to “exercise themselves in shooting and regulating their guns. Found several of them that had their sights moved by accident, and others that wanted some little alterations all which were completely rectified in the course of the day except my Small Rifle which I found wanted cutting out.” That is, the rifling ridges in the bore of his gun had worn down from continued use and were no longer imparting the spin to the bullet that ensured accuracy. The grooves in the bore needed to be cut deeper.

On the following day Clark reported with a mixture of satisfaction and pride that “John Shields cut out my small rifle and brought her to shoot very well. The party owes much to the ingenuity of this man, by whom their guns are repaired when they get out of order, which is very often.”

Firing a Flintlock

Firing a Flintlock

Demonstration by Scott Eckberg, courtesy U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service

See also How Flintlocks Work.

The Corps of Discovery carried several types of handheld weapons for hunting and self-defense. Among them were fifteen “short” rifles like this one, which Lewis procured in 1803 from the new U.S. arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, on the Potomac River near Washington, D.C. Possibly they were prototypes of the first official U.S. Army rifle, of which Secretary of War Henry Dearborn ordered 4,000 in 1804.

The Model 1803 fired a .53 caliber ball from a .54 caliber barrel with an effective range of up to 200 yards, with 25% greater killing power than the famed Kentucky (or Pennsylvania) “long” rifle, which fired a .44 caliber ball from a .45 caliber barrel. Clearly, the Model 1803 Harpers Ferry was the preferred weapon for dealing with big game such as grizzlies and bison.

None of the weapons the Corps of Discovery carried is known to exist today. All of them, as well as powder, lead, powder horns, shot pouches, kettles, axes, and other public property were sold at a public auction in St. Louis shortly after the expedition’s end in September 1806, for a total of $408.62.

—Joseph Mussulman with David E. Nelson, technical advisor

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to Muskets and Rifles:

- Harpers Ferry National Historic Park

- Harpers Ferry to Brownsville (Inspiration Trip)