© 2000 Jim Wark, Airphoto.

On 2 November 1804 below the Knife River Villages, work begins on the expedition’s winter fortification. The men’s quarters, storage rooms, and the 16-foot pickets, are designed for defense against hostile Indians, especially the Sioux, who would be quite troublesome, although they never attacked the fort directly. “This place we have named Fort Mandan,” Lewis recorded, “in honour of our Neighbours”—their kind and congenial Mandan Indians. Here they celebrate their second Christmas and New Year’s Day.

On 28 February 1805, sixteen enlisted men are assigned to hew six canoes from cottonwood logs, and they finish them in 22 days. Meanwhile, the rest of the men make rope, leather clothing and moccasins, cured meat, and battle axes to trade for corn. Lewis prepares botanical, zoological, and mineralogical specimens for shipping back to President Jefferson. Clark works on his Fort Mandan maps.

“All the party in high Spirits,” Clark wrote approvingly, “but fiew nights pass without a Dance they are helth. except the—vn. [venereal]—which is common with the Indians and have been communicated to many of our party at this place— those favores bieng easy acquired. all Tranquile.”

By the time they are ready to leave Fort Mandan, they add some key members to the permanent party: Toussaint Charbonneau, his wife and infant son—Sacagawea and Jean Baptiste, and French trader Jean-Baptiste Lepage. Each would play critical roles in the expedition’s journey to the Pacific Ocean.

The Cheyennes

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Many, including the expedition members, misheard the people’s name as ‘chien’—French for ‘dog’. Their name actually comes from the Sioux exonym shahíyena, perhaps meaning ‘people of alien speech’. The captains thought that they might make good trading partners.

The Arikaras

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Spelled variously in the expedition journals, Clark sometimes called the Arikara people Pawnee due to their similar linguistic origins—both were Caddoan-speaking people. Weakened by smallpox and Sioux attacks, they would have significant impact on American fur trade interests on the Upper Missouri and affect the lives of several expedition members.

Joseph Gravelines

by Clay S. Jenkinson

The Arikara-resident trader and interpreter Gravelines proved to be so reliable and so good at the immediate tasks put to him that long after the Lewis and Clark Expedition he was employed by the United States government to represent its interests among the Arikara.

The Assiniboines

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Assiniboines were nomadic hunter-gatherers roaming primarily along the rivers in Saskatchewan and western Manitoba. They often dropped south into present-day Montana and North Dakota, especially in their role as middle-men between the English trading companies and the Hidatsas to the south.

The Mandans

by Kristopher K. Townsend

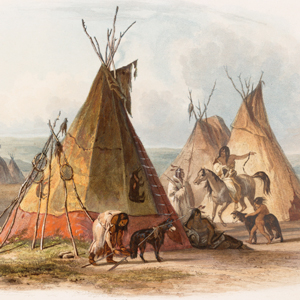

After the 1781 smallpox epidemic, the Mandan had moved into to a more defensible position in two villages immediately south of the Hidatsa at the Knife River. The Mandan-Hidatsa alliance had developed many years prior, and the two tribes previously shared their large hunting territory to the west.

The Hidatsas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Prior to the expedition, the Hidatsa had settled in three villages just north of two Mandan villages in a complex now called the Knife River Villages. There, they practiced horticulture and hunting in the manner of the Plains Village tradition.

The Lakotas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Presently known as the Lakota people, Lewis and Clark most often called them the Tetons. There were three main groups: Oglala, Brule, and Saone. The bands typically lived separately, hunted freely within each other’s territory, and came together for community events.

The Iowas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Iowa culture blended lifeways and customs of their neighbors: Horticulture and a well-defined, patrilineal class system was learned from the Sioux, a clan system was adapted from Algonquian-speaking neighbors, and like the Plains culture, they practiced the summer village method of hunting the American bison.

The Yankton Sioux

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Yankton along with the Yanktonai make up the Western Dakota division of the Dakota People. Although the Yankton and Yanktonai sometimes considered themselves to be one people, their separate locations resulted in a unique history for each.

Sacagawea

Articles and journal entries

Speaking Hidatsa and Shoshone, she was an interpreter beyond value yet never on the payroll. Still, Sacagawea remains the third most famous member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The Knife River Villages

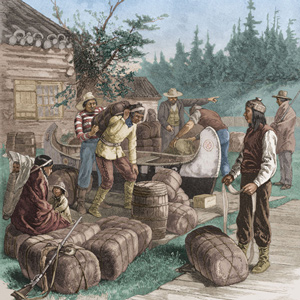

Marketplace

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Reaching the mouth of the Knife River on 27 October 1804, the expedition arrived in the midst of a major agricultural center and marketplace for a huge mid-continental region. The five permanent earth lodge communities there offered a panorama of contemporary Indian life.

Synopsis Part 2

Fort Mandan to the Marias River

by Harry W. Fritz

Near the mouth of the Knife, in late October 1804, the expedition settled down for the winter. After the river ice broke up, the keelboat left for St. Louis and six new dugout canoes headed the opposite direction, up the Missouri river.

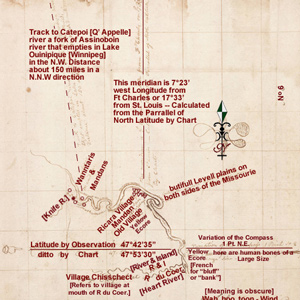

The Fort Mandan Observations

22 December 1804–3 April 1805

by Robert N. Bergantino

In January 1798, Thompson took celestial observations at the villages and determined them to be at a latitude of 47°17’22″N and a longitude of 101°14’24″W. Why then did Lewis and Clark think it necessary to take twenty-six observations?

Fort Mandan by Air

"most perfect harmony"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis attested that his men were “in excellent health and sperits, zealously attached to the enterprise, and anxious to proceed; not a whisper of murmur or discontent to be heard among them, but all act in unison, and with the most perfect harmony.”

The Northern Lights

Aurora borealis

by Barbara Fifer

“Late at night we were awaked by the sergeant on guard to see the beautiful phenomenon called the northern light….” What did Meriwether Lewis and William Clark understand about the aurora borealis? Scientific theories of their time may sound a bit fanciful today.

Clark’s Fort Mandan Maps

by Joseph A. Mussulman

While wintering over at Fort Mandan, Clark made a series of maps based on Indian information and previous traders such as John Evans and François Larocque.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.