Originally published in We Proceeded On, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation[1]Joseph D. Jeffrey, “Meriwether Lewis at Harpers Ferry”, We Proceeded On, May 2016, Volume 42, No. 2. The original article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol42no2.pdf#page=8.

Then and Now

Harpers Ferry from Maryland Heights. The Point is at the junction of the Potomac, entering from right, and Shenandoah Rivers.

The early days of March 1803 marked the end of the two-year planning phase for Thomas Jefferson‘s western expedition of exploration. The planning activity had been carried out largely in the sanctity of President Jefferson’s office.[2]William Seale, The President’s House, 2 vols. (Washington: White House Historical Association and National Geographic Society, 1986), 1:95. Those days also began a four-month period during which Meriwether Lewis, as the first and yet sole member of the Corps of Discovery, constantly traversed the roads connecting Washington, Harpers Ferry, Lancaster, and Philadelphia assembling his supplies and taking cram courses that would qualify him to be the expedition’s resident scientist. Curiously though, the progress of events at Harpers Ferry set the pace and dictated the timing of Lewis’s travels during that period. It was on the Harpers Ferry Armory and Arsenal that Lewis relied for guns and hardware that would meet his unique requirements.

In 1803, the Harpers Ferry Armory was a new facility. In retrospect, it could be considered the precursor for a two-hundred-year succession of government agencies that drew on the national talent available at the time and that performed outstanding services in their early years. In its ability to implement new designs and adapt them for production, the Harpers Ferry Armory was unique, exactly the combination laboratory, job-shop, and manufactory Lewis needed.

Today Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, is a small town, the lower part of which is a national historical park. The clean streets and handsomely restored buildings set on the point of land at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers in a rural mountainous setting, make it a visual delight for the casual sightseer as well as the Civil War buff. There the National Park Service has placed historical emphasis on the Civil War period. Yet fifty-six years before abolitionist John Brown’s raid on the armory, Harpers Ferry played its significant part at the start of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

A Distinguished History

Harpers Ferry Large Arsenal (1803)

Etching by Joseph Jeakes from the original painting by William Roberts. Courtesy the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, the New York Public Library. “Junction of the Potomac and Shenandoah, Virginia.” New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed 1 March 2016, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7b55-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

The Point and Large Arsenal, c. 1803. View to the east looking down the Potomac with the Shenandoah flowing in from the right. Maryland shore, left, with the ferry in midstream. The arsenal was built 1799–1800.

While Lewis was the first historic personage to do business with the Harpers Ferry Armory, he was not the first to have his name associated with the area. As far back as the time of the French and Indian War, George Washington, then an officer in the British colonial militia, was familiar with the upper Potomac River and the line of forts to Pittsburgh and beyond. Before the Revolution, Washington had also served as surveyor for Virginia’s British governor, Lord Fairfax, and after the Revolution as president of the Patowmack (land development) Company.[3]Dave Gilbert, A Walker’s Guide to Harpers Ferry (Harpers Ferry: Harpers Ferry Historical Association, Third Edition, 1991), 10, 38. Washington’s familiarity with the area was later instrumental in establishing the Federal Armory and Arsenal at Harpers Ferry.

Unlike Washington, Thomas Jefferson did little traveling west of his Virginia estates (Monticello and Poplar Forest) or west of the Atlantic Coast centers of population. However, at the time he was elected a Virginia representative to the 1783 Continental Congress, he decided to take a westerly route to Philadelphia by descending the Shenandoah River through the village of Harpers Ferry.[4]Ibid., 41. See also Merrill D. Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation—A Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 268. On 25 October he climbed the steep hill above the town to a rocky outcrop, where, so impressed with the mountain and river view, he described the setting in his book Notes on the State of Virginia. Wrote Jefferson as he looked to the east:

On your right comes up the Shenandoah, having ranged along the foot of the mountain a hundred miles to seek a vent. On your left approaches the Patowmac in quest of a passage also. In the moment of their junction they rush together against the mountain, rend it asunder, and pass off to the sea.—This scene is worth a voyage across the Atlantic.[5]William Peden, ed., Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (New York: W.W. Norton Co., 1982, reprint of the 1785 original), 19.

Long before Washington and Jefferson, the Harpers Ferry site was on the natural transportation corridor connecting the frontier villages of Fredericktown [Frederick, Maryland] and Charles Town [then Virginia, now West Virginia], and continuing on to the few settlements to the southwest in the Shenandoah Valley. In 1733, a trader, Peter Stephens, recognized the possibilities of the site. Noting that the Potomac River was the major travel impediment on the route, he set up a primitive ferry service.[6]Visitors brochure, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park (National Park Service, 1992).

Fourteen years later millwright Robert Harper, alert to the water power possibilities of the rivers, bought out Stephens’ ferry operation and took a deed on Stephens’ squatter rights holdings. Harper proceeded to put his new holdings on a firm legal basis and in 1751 obtained a land patent from the Royal Governor and exclusive charter for the ferry concession from the Virginia General Assembly. In 1763, the town of “Shenandoah Falls at Mr. Harper’s Ferry” was established by act of the Virginia General Assembly.[7]Gilbert, Walker’s Guide, 40. Harper’s combined mill and ferry boat operation impressed land developer/surveyor George Washington with the larger possibilities of the site.

In its early days the site was referred to as Harper’s Ferry. Today it is Harpers Ferry without the apostrophe.

In 1775, Robert Harper began construction of a stone house, but due to the wartime scarcity of labor it was not completed until 1782. Unfortunately Harper died in October of that year without ever living in the house, but the name stuck. From 1782 to 1803, the building functioned as the town’s only tavern and served, among others, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.[8]Ibid. As an 1803 tavern it was certainly visited by Meriwether Lewis and, in keeping with the custom of the times, quite possibly housed Lewis during his stay.

In 1794, Congress passed legislation “for the erecting and repairing [translated to mean construction, equipping, and maintenance] of Arsenals and Magazines.” The first of two national armories/arsenals was then planned for Springfield, Massachusetts. George Washington, now president, was given wide discretionary powers in executing the legislation and, not surprisingly, selected Harpers Ferry for the second site.

The U.S. government in 1796 purchased 118 acres from Harper’s heirs for its new facility, referred to officially as the “United States Armory and Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry.” Construction began in 1799.[9]Ibid., 38. The terms armory and arsenal seem to have been used somewhat interchangeably, although armory meant a manufacturing facility, and arsenal referred to a storage site for completed arms.

Although there was much criticism of his selected site because of its flood damage potential, Washington believed it to be ideal because of the available water power, access to raw materials, secure position, and proximity to the new capital. Washington’s view prevailed.[10]Ibid. It might be noted that for the sixty-three years the armory was in production, floods never shut it down. It took the ravages of Civil War to finally bring its demise; by that time it had, in any event, outlived its usefulness. After the Civil War, floods harassed the town and closed the last commercial mills in 1936.

By 1801, the Harpers Ferry Armory was producing its first weapons. The workmen were skilled artisans drawn from the Philadelphia area. Their specialty was individual piecework, but the armory was able to begin mass production of rifles shortly after Lewis’s visit.

Lewis’s First Visit

Freed from the restrictive Washington atmosphere in March 1803, Lewis hit the ground running as he prepared for the western exploration. For four months his track was difficult to follow, as Jefferson discovered. One quick inspection of equipment available from the regular army supply depot, Schuylkill Arsenal at Philadelphia, convinced Lewis that hardware to meet his anticipated special needs (such as for guns, tomahawks, boat frame, and the like) was not available through normal military provisioning channels.

The new facility at Harpers Ferry with its talented work force was obviously the source of choice. Lewis lost no time in getting his logistic supply line in order. Beginning on 14 March, a succession of orders emanated from the War Department. The first, and of primary interest, was from Secretary of War Henry Dearborn himself, addressed to Joseph Perkins, superintendent of the Harpers Ferry Arsenal:

14th March 1803

Sir:

You will be pleased to make such arms & Iron work, as requested by the Bearer Captain Meriwether Lewis and to have them completed with the least possible delay. I am

&c.

H. Dearborn[11]Dearborn to Perkins, 14 March 1803. In Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:75–76.

The secretary’s order in hand, and now having a good idea where the various classes of equipment were to be obtained, Lewis’s priority rested with specialty items that would require his design and approval. Accordingly, he hurried to Harpers Ferry where he arrived about 16 March.

With a little imagination one can picture some of Harpers Ferry today as Lewis would have found it in 1803. In addition to Jefferson Rock and Harper House, three other sites in the lower town reflect the Lewis era. On Potomac Street is a modest building with a sign in front claiming that it was built in 1799 to be the home of the armory superintendent. Now near the railway station, in 1803 it was across the street from the armory’s then-main entrance. (All armory buildings have long since disappeared, their site now covered by an elevated railroad grade.) Since the house lies outside the park boundary, it has not been historically authenticated by the National Park Service. However, dedicated Lewis and Clark followers may well accept it for what it purports to be.

The second Lewis-related site is at the point of land (the “Point”) where the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers converge. There is displayed a copy of an 1803 lithograph showing the large arsenal with the rivers beyond, surrounded by mountains, and with a ferry boat midstream from the Maryland shore as Lewis would have ridden it several times to and from Frederick[town].[12]A print from the original, shown at Monticello as part of Jefferson’s 250th birthday celebration, is dated c. 1810. This is reproduced in Susan R. Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at … Continue reading Here, truly, is depicted the landscape as Lewis would have seen it, not too different from today’s similar mountain and river vista.

The third site as seen today is the foundation of the large arsenal, now outlined in stone in the grass of a pleasant park-like setting. The large arsenal (so called to differentiate it from the later ‘small’ arsenal) shown in the 1803 lithograph was a two-story building with attic, built in 1799–1800 and measuring 125 by 32 feet, used to store completed arms manufactured in the armory.[13]Gilbert, Walker’s Guide, 27.

Iron-framed Boat Delays

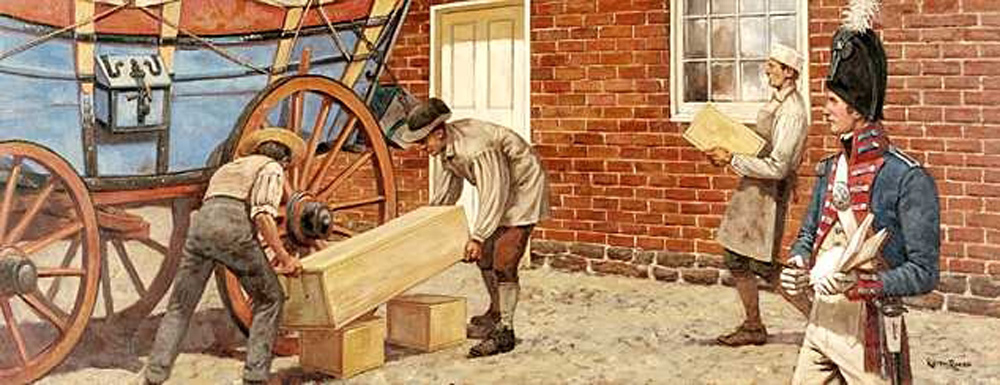

Inspecting the Iron-Framed Boat

by Keith Rocco/Tradition Studios 2002. Provided by Harpers Ferry National Historic Park, U.S. National Park Service.

Meriwether Lewis (right) and Joseph Perkins, superintendent of the Harpers Ferry armory, inspect the frame of the captain’s collapsible iron boat.

Lewis’s travels were now so unpredictable that it was difficult for Jefferson to keep his paternal eye on his protégé’s progress. Indeed, as Jefferson somewhat petulantly suggested, he had heard nothing from Lewis for six weeks or so after 7 March 1803.[14]Jefferson to Lewis, 23 April 1803. Reported in Jackson, Letters, 43. Of course, some portion of that six weeks may have been due to Jefferson’s own absence from Washington while Lewis remained in the capital. It was Jefferson’s yearly custom to take an early spring break for a month at Monticello, his home near Charlottesville, Virginia.[15]The pattern of Jefferson’s annual spring break seems to have been established shortly after his first inaugural. He moved into the President’s (White) House 19 March 1801, and shortly … Continue reading With that pattern, it is quite probable that Jefferson departed Washington on or shortly after 7 March, eight days ahead of Lewis’s 15 March departure.[16]The two dates may be logically reconciled. Lewis’s 15 March departure date was given in Treasury Secretary Gallatin’s 14 March letter to Jefferson. See Jackson, Letters, 27. This same … Continue reading In any event, Lewis was not keeping his mentor well advised as to his movements although, as a one-man task force, he was literally scheduling his activities on a day-to-day basis that stretched his intended one-week stay at Harpers Ferry to a month.

Finally, on 20 April 1803, Lewis wrote Jefferson to explain, if not his silence, at least his activity:

My detention at Harper’s Ferry was unavoidable for one month, a period much greater than could reasonably have been calculated on; my greatest difficulty was the frame of the canoe, which could not be completed without my personal attention to such portion of it as would enable the workmen to understand the design perfectly . . . . My Rifles, Tomahawks & knives are preparing at Harper’s Ferry, and are already in a state of forwardness that leaves me little doubt of their being in readiness in due time.[17]Lewis to Jefferson, 20 April 1803. Jackson, Letters, 38–40.

Lewis’s letter went on further to explain that he was unwilling to risk the iron-framed boat‘s design on theoretical calculations alone. He, therefore, decided to conduct a “full experiment” after which “I was induced from the result of this [successful] experiment to direct the iron frame of the canoe to be completed.” With a transportable weight of only 99 pounds and able to carry a load of 1,770 pounds, the canoe seemed to justify Lewis’s optimism as to its potential. That the “iron canoe” failed of its purpose was not the fault of the armory’s skill or of Lewis’s great idea. Much later, when the time came to put the iron frame to practical use following the Great Falls of the Missouri portage, the natural resources of that local area, on which Lewis had planned to rely, simply did not provide the necessary waterproofing material for seams of the boat’s elkskin covering.

Lewis departed Harpers Ferry 18 April for Lancaster and Philadelphia, confident that all was now firmly on track. Jefferson, not yet in receipt of Lewis’s 20 April letter, wrote to him 23 April noting that two army officers had informed him (Jefferson) they had seen Lewis in Frederick about 20 April and that Lewis had been detained in Harpers Ferry until 18 April.[18]Jefferson to Lewis, 23 April 1803. Jackson, Letters, 43.

Jefferson’s concerns about Lewis’s whereabouts during this period of silence were also expressed in the president’s letter to Lewis Harvie. Harvie had been selected to be Lewis’s replacement as Jefferson’s secretary. Jefferson apologized for not moving Harvie into the job earlier, but did not want it to appear that he was dissatisfied with Lewis’s actions or in a hurry to replace him. Jefferson explained that he had anticipated Lewis’s return to Washington and start on his Mississippi expedition [still carrying on the fiction of the purpose, see Jefferson’s Secrecy] some time earlier, but only two days earlier had learned that Lewis had been detained at Harpers Ferry a month instead of a week.[19]Jefferson to Harvie, 22 April 1803. Jackson. Letters, 41.

The Transportation Challenge

“Artist’s rendering of Captain Meriwether Lewis inspecting his weapons and articles before departing for Pittsburgh, Pa. on July 8, 1803.”[20]“Meriwether Lewis at Harpers Ferry,” Harpers Ferry National Historic Park, www.nps.gov/media/photo/gallery.htm?pg=2734773&id=2A7D3A84-1DD8-B71C-0704CA9F144A0AB9 accessed 14 May 2022.

On 29 May 1803 Lewis reported to the president his successful completion of preparation in Philadelphia and planned departure for Washington June 6 or 7.[21]Lewis to Jefferson, 29 May 1803 in Jackson, Letters, 51. Lewis’s major chore now was to make arrangements for transport of his small mountain of stores from Philadelphia and Harpers Ferry to Pittsburgh, the embarkation point for the expedition’s keelboat [the barge].

Transport of all military materials from the various supply centers to forts and outposts was under the control of area “military agents” of the War Department. For the middle Atlantic area, which included Philadelphia, Harpers Ferry, and Pittsburgh, the military agent was one William Linnard. Lewis called on Linnard in Philadelphia to state his requirements and then backed up his request with a letter dated 10 June 1803.[22]Lewis to William Linnard, 10 June 1803. Jackson, Letters, 53. Lewis emphasized that the stores would weigh at least 3,500 pounds and that the road by “which from necessaty they must travel is by no means good.” Accordingly, he recommended a five-horse team.

Last minute delays held Lewis in Philadelphia until 17 June.[23]Richard Dillon, Meriwether Lewis—A Biography (New York: Coward McCann, 1965), 46. He then returned to Washington hoping everything would fall into place. Certainly his attention to detail had provided for every reasonably anticipated contingency. Lewis’s last days in Washington were a flurry of activity.[24]Lewis was receiving last minute instructions, some in written form (including the famous letter of general credit), from Jefferson almost to the moment of departure. See Jefferson to Lewis, 4 July … Continue reading He had intended to visit his mother at Locust Hill (near Charlottesville), but so anxious was he to get started west, he could only write her that “circumstances have rendered this impossible.”[25]Lewis to Lucy Marks, 2 July 1803. Jackson, Letters, 100. As Lewis informed his mother, he was to depart Washington on 4 July 1803. Actually Lewis left the city, now for the last time, on 5 July. His one-day delay was probably due to last minute details and a possible July 4th Independence Day–Louisiana Purchase celebration.[26]A footnote in Jackson, Letters, 106, gives the 5 July Lewis departure date. Jim Large notes that news of the Louisiana Purchase reached Washington on 3 July, giving cause for a double celebration on … Continue reading

Linnard started the transport wagon west from Philadelphia in timely fashion. Unfortunately, with bureaucratic inefficiency, he failed to verify the wagon’s carrying capability. As Lewis later reported to Jefferson, the wagon passed Harpers Ferry 28 June; however, “The waggoner determined that his team was not sufficiently strong to take the whole of the articles that had been prepared for me at this place [i.e. Harpers Ferry] and therefore took none of them.”[27]Lewis to Jefferson, 8 July, 1803. Jackson, Letters, 106.

It is not clear when Lewis learned of the transportation breakdown at Harpers Ferry. But on 5 July he was in Fredericktown, thirty-five miles from Washington and twenty miles from Harpers Ferry seeking transport. There he “engaged a person with a light two horse-waggon who promised to set out with them this morning [i.e. 8 July] for H. Ferry . . . .”[28]Ibid.

However, once again the promised transport failed at the appointed time. Lewis’s intestinal fortitude must have been sorely tried. On that same day he engaged yet another person now scheduled to depart Harpers Ferry the morning of 9 July. This time Lewis must have been sure of the driver, team, and wagon since he planned his own departure from Harpers Ferry a day ahead of the wagon.

Attesting to the high quality of work performed by the Harpers Ferry Armory, Lewis wrote the president, “Yesterday [7 July] I shot my guns and examined the several articles which had been manufactered for me at this place; they appear to be well executed.”[29]Ibid.

Lewis departed Harpers Ferry for the last time the afternoon of 8 July, by “the rout of Charlestown, Frankfort, Uniontown [Pennsylvania] and Redstone old fort [now Brownsville, Pennsylvania].”[30]Ibid. His direction was now irrevocably west. He reported to Jefferson his arrival in Pittsburgh 15 July with nothing happening on the trip “worthy of relation.”[31]Lewis to Jefferson, 15 July 1803. Jackson, Letters, 110. Lewis’s final references to Harpers Ferry were made in a 22 July letter to Jefferson. “—the knives that were made at Harper’s ferry will answer my purposes equally as well and perhaps better . . . . The Waggon from Harper’s ferry arrived today, bringing everything with which she was charged in good order.”[32]Lewis to Jefferson, 22 July 1803. Jackson, Letters, 111–12.

Lewis’s Rifles and Equipment

The inscription on the lock reads “Harpers Ferry, 1803”.[33]“Meriwether Lewis at Harpers Ferry,” Harpers Ferry National Historic Park, https://www.nps.gov/media/photo/gallery.htm?pg=2734773&id=2A7D3A84-1DD8-B71C-0704CA9F144A0AB9 accessed 14 … Continue reading

We are concerned more with the circumstances of the Harpers Ferry acquisition than the details of the articles themselves. However, from Donald Jackson’s Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition[34] Jackson, Letters, 69–99. and other references one may deduce what articles came from Harpers Ferry. One author in 1968 listed as probably acquired there:[35]Stuart E. Brown, Jr., Guns of Harpers Ferry (Berryville, Virginia: Virginia Book Co., 1968).

- 15 rifles

- 12 pipe tomahawks

- 18 tomahawks

- 36 pipe tomahawks “for Indian presents”

- 24 large knives

- 15 powder horns and pouches complete

- 15 pairs of bullet molds

- 15 wipers or gun worms

- 15 ball screws

- 15 gun slings

- Extra parts of locks, and tools and parts for replacing arms

- 40 fish giggs such as the Indians use with a single barb point

- Collapsible iron frame for a canoe

- 1 small grindstone

This listing, if not wholly accurate, is certainly representative of what Lewis obtained at Harpers Ferry. The rifles and rifle accessories, of course, were of primary importance.

Other than a brief note in the park’s visitors brochure that arms produced here were used by Lewis and Clark, the only signage today at the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park referencing Lewis and Clark is a small card in the Master Armorer’s House (c. 1858), alongside an 1803 rifle reading:

U.S. Model 1803 Flintlock Rifle. The first rifles made at Harpers Ferry reflect the popular American design of the Pennsylvania and Kentucky rifles. Like the early muskets, craftsmen produced the various parts of this rifle by hand. Many historians believe that Lewis and Clark traveled west with these rifles during their Louisiana Territory expedition in 1803–1804.

That the signage is in error as to the dates of the expedition makes it suspect, or at least unclear, also as to the type and model designations of the Lewis rifles. Biographer Richard Dillon gives some characteristics of the Lewis rifles and asserts that so efficient was the Lewis design that the Secretary of War ordered them (presumably meaning the U.S. Model 1803 noted in the NPS sign) into mass production with only one or two minor changes.[36]Dillon, Meriwether Lewis, 43.

A detailed analysis of the Lewis rifles is beyond the intended scope of this article. However, any person interested in the gun history and subsequent influence of the Lewis design might find helpful the references provided by the Harpers Ferry National Park historian’s office cited in the end note below.[37]Citations furnished by the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park historian’s office that provide some details of the Lewis rifle design: David F. Butler, United States Firearms, the First … Continue reading

In Perspective

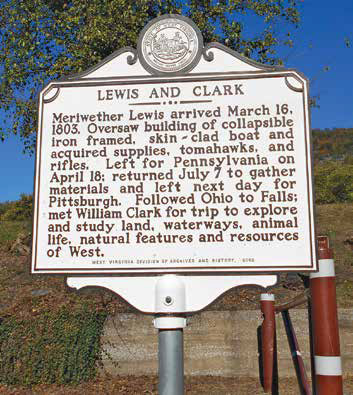

Transcription:

Meriwether Lewis arrived March 16, 1803. Oversaw building of collapsible iron framed, skin-clad boat and acquired supplies, tomahawks, and rifles. Left for Pennsylvania on April 18; returned July 7 to gather materials and left Ohio to Falls; met William Clark for trip to explore and study land, waterways, animal life, natural features and resources of the West.

West Virginia Division of Archives and History, 2002.

No expert’s knowledge or indeed any knowledge of rifles is necessary to appreciate Harpers Ferry today. But one should be armed with foreknowledge to find the elusive 1803 tracks of Meriwether Lewis. So plan to climb the quarter-mile section of Appalachian Trail that leads up to the panoramic view at Jefferson Rock. Then stand below at “the Point” and compare the pictorial representation of the 1803 scene with today’s mountain and river vista. Walk through Harper House, the oldest surviving building in the park, and see it in the mind’s eye, not as presented in its later years, but as familiar to Lewis while engaged in conversation with townspeople and armory artisans over a friendly ale. Nearby, walk slowly by the reputed superintendent’s home where Lewis, after presenting his impressive credentials and consistent with military niceties of the time, would certainly have been socially entertained of an evening as the not-yet-famous, but nevertheless illustrious representative of the United States president. Finally, view the stone foundation of the large arsenal and imagine Lewis at the door giving a final instruction for loading the supply wagon, eager to start west within the hour on his adventure.

In its very early days the Harpers Ferry Armory and Arsenal made a notable contribution to the success of the expedition. Backed by this history, Harpers Ferry is a significant site on the eastern Lewis and Clark Trail. For another perspective, see on this site Harpers Ferry by Air.

About the Author

Joseph D. Jeffrey is a retired naval officer and aviator. He is the former chief legal advisor in the Federal Aviation Administration, Office of Aircraft Safety Standards. He is a member of the National Lewis & Clark Trail Coordination Committee serving as state chairman of the Virginia, West Virginia, District of Columbia area.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to Harpers Ferry:

- Harpers Ferry National Historic Park

- Harpers Ferry to Brownsville (Inspiration Trip)

Notes

| ↑1 | Joseph D. Jeffrey, “Meriwether Lewis at Harpers Ferry”, We Proceeded On, May 2016, Volume 42, No. 2. The original article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol42no2.pdf#page=8. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | William Seale, The President’s House, 2 vols. (Washington: White House Historical Association and National Geographic Society, 1986), 1:95. |

| ↑3 | Dave Gilbert, A Walker’s Guide to Harpers Ferry (Harpers Ferry: Harpers Ferry Historical Association, Third Edition, 1991), 10, 38. |

| ↑4 | Ibid., 41. See also Merrill D. Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation—A Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 268. |

| ↑5 | William Peden, ed., Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (New York: W.W. Norton Co., 1982, reprint of the 1785 original), 19. |

| ↑6 | Visitors brochure, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park (National Park Service, 1992). |

| ↑7 | Gilbert, Walker’s Guide, 40. |

| ↑8 | Ibid. |

| ↑9 | Ibid., 38. |

| ↑10 | Ibid. |

| ↑11 | Dearborn to Perkins, 14 March 1803. In Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:75–76. |

| ↑12 | A print from the original, shown at Monticello as part of Jefferson’s 250th birthday celebration, is dated c. 1810. This is reproduced in Susan R. Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello (New York: Harry N. Abrams, and Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, Inc., 1993), 190, 92. However, the NPS display copy is characterized as an 1803 print. See also Gilbert, Walker’s Guide, at p. 26 for a reprint of the lithograph. |

| ↑13 | Gilbert, Walker’s Guide, 27. |

| ↑14 | Jefferson to Lewis, 23 April 1803. Reported in Jackson, Letters, 43. |

| ↑15 | The pattern of Jefferson’s annual spring break seems to have been established shortly after his first inaugural. He moved into the President’s (White) House 19 March 1801, and shortly thereafter “was away for a month’s rest at Monticello.” See Seale, The President’s House, 1:93. That it was a yearly event for Jefferson to go “to Monticello for his usual spring holiday,” see Peterson, Jefferson and The New Nation, 804. |

| ↑16 | The two dates may be logically reconciled. Lewis’s 15 March departure date was given in Treasury Secretary Gallatin’s 14 March letter to Jefferson. See Jackson, Letters, 27. This same letter also notes Jefferson’s absence from Washington at the time, saying in effect that nothing of importance in the Treasury Department would be done “till you return.” |

| ↑17 | Lewis to Jefferson, 20 April 1803. Jackson, Letters, 38–40. |

| ↑18 | Jefferson to Lewis, 23 April 1803. Jackson, Letters, 43. |

| ↑19 | Jefferson to Harvie, 22 April 1803. Jackson. Letters, 41. |

| ↑20 | “Meriwether Lewis at Harpers Ferry,” Harpers Ferry National Historic Park, www.nps.gov/media/photo/gallery.htm?pg=2734773&id=2A7D3A84-1DD8-B71C-0704CA9F144A0AB9 accessed 14 May 2022. |

| ↑21 | Lewis to Jefferson, 29 May 1803 in Jackson, Letters, 51. |

| ↑22 | Lewis to William Linnard, 10 June 1803. Jackson, Letters, 53. |

| ↑23 | Richard Dillon, Meriwether Lewis—A Biography (New York: Coward McCann, 1965), 46. |

| ↑24 | Lewis was receiving last minute instructions, some in written form (including the famous letter of general credit), from Jefferson almost to the moment of departure. See Jefferson to Lewis, 4 July 1803, Jackson, Letters, 105. |

| ↑25 | Lewis to Lucy Marks, 2 July 1803. Jackson, Letters, 100. |

| ↑26 | A footnote in Jackson, Letters, 106, gives the 5 July Lewis departure date. Jim Large notes that news of the Louisiana Purchase reached Washington on 3 July, giving cause for a double celebration on the 4th—a celebration that might well have detained Lewis in Washington an extra day. |

| ↑27 | Lewis to Jefferson, 8 July, 1803. Jackson, Letters, 106. |

| ↑28 | Ibid. |

| ↑29 | Ibid. |

| ↑30 | Ibid. |

| ↑31 | Lewis to Jefferson, 15 July 1803. Jackson, Letters, 110. |

| ↑32 | Lewis to Jefferson, 22 July 1803. Jackson, Letters, 111–12. |

| ↑33 | “Meriwether Lewis at Harpers Ferry,” Harpers Ferry National Historic Park, https://www.nps.gov/media/photo/gallery.htm?pg=2734773&id=2A7D3A84-1DD8-B71C-0704CA9F144A0AB9 accessed 14 May 2022. |

| ↑34 | Jackson, Letters, 69–99. |

| ↑35 | Stuart E. Brown, Jr., Guns of Harpers Ferry (Berryville, Virginia: Virginia Book Co., 1968). |

| ↑36 | Dillon, Meriwether Lewis, 43. |

| ↑37 | Citations furnished by the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park historian’s office that provide some details of the Lewis rifle design: David F. Butler, United States Firearms, the First Century 1776–1875 (New York: Winchester Press, 1971), 74–77; Robert M. Reilly, U.S. Martial Flintlocks (Lincoln, Rhode Island: Andrew Mowbray, Inc., 1986), 125–26; Kirk Olson, “A Lewis & Clark Rifle?,” American Rifleman (May 1985), 23–25, 66–68; Brown, Guns of Harpers Ferry. [Editorial note, 2016: See also special issue of We Proceeded On, 32 (May 2006) on firearms; Jim Garry, Weapons of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 2012). |