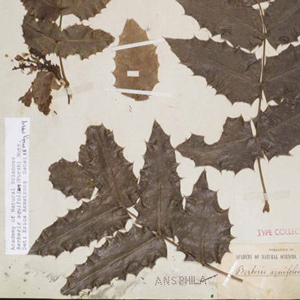

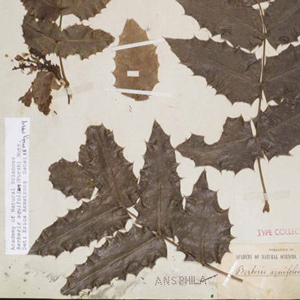

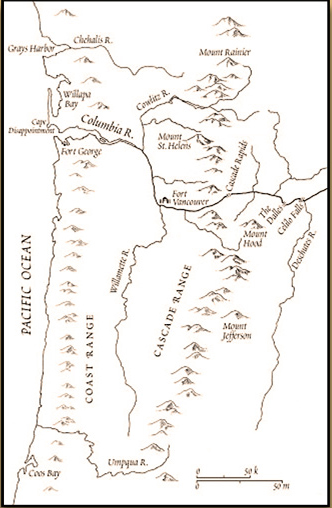

Pressed Beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax)

© 2018 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

This beargrass specimen was collected by the photographer on the Lolo Trail in the area that the Corps descended into Hungery Creek. The blotting paper is similar to the paper Lewis used in the field.

Specimen Presses

A botanist presses specimens of plants for study and comparison with other specimens of similar species that have been gathered at different times and places, worldwide. Meriwether Lewis knew that his studies in the field would be backed up by the most prominent cabinet—that is, laboratory—botanists of his day.

Among them was to be Frederick Pursh (1774-1820), a German botanist whom Lewis hired at Philadelphia in May of 1807, paying him a total of seventy dollars to assist him in preparing his collection for a planned but never written publication of his own.[1]Jackson, Letters, passim. Pursh examined 124 of Lewis’s specimens, verified or corrected Lewis’s descriptions, wrote many new “diagnoses,” and assigned names to the species that were new to science.[2]It is estimated that seventy or seventy-five specimens were new to science when Lewis collected them. Pursh honored Lewis by naming four new species after him: Linum lewisii (LEE-noom … Continue reading He also painted water colors of thirteen of those, and in 1814 included them all in his two-volume Flora Americae Septentrionalis (FLO-ruh a-MAY-ree-kay sep-TEN-tree-oh-NAL-iss; Plants of North America).

Botanical Collector

A botanical collector like Meriwether Lewis had to begin the process of preserving his specimens as soon as possible after picking them, to forestall wilting and shriveling. The field botanist must place the leaves, stems, flowers, fruits, and roots on sheets of mounting paper with the utmost care and foresight. The whole point is to preserve every specimen in a way that will enable the cabinet botanist to examine minute details that will facilitate the writing of a definitive analysis of each specimen. Immediately, each mount must be covered with a sheet of soft, loose-textured, highly absorbent bibulous (Latin for “drinking”) or “blotter” paper, in order to draw all moisture out of the specimen. In some cases a discreet dissection may be necessary to provide maximum value to the collection. A memorandum is added containing the date and place the specimen was found, perhaps with a very brief description including known uses of the plant, and the collector’s name. Stacks of specimen mounts and blotter papers are weighted down or tied together tightly, then monitored frequently until the drying is complete.

The Corps of Discovery’s Lewis was a conscientious field botanist. The collector must monitor the drying process carefully including daily awareness of ambient temperature and humidity to be sure the specimens remain intact and free from mold or decay and to guard against invading insects. If possible, the specimen must be exposed occasionally to warm sunlight and dry air. This must have been a serious challenge to Lewis under the field conditions he endured from day to day. It certainly was at Fort Clatsop, where the average daily humidity probably ranged from 70 to 90 percent, and it rained all but six days between their arrival at the coast and their departure on 23 March 1806. In short, until the specimens are deposited in a secure collection facility known as a herbarium, botanizing is a tedious, time-consuming procedure which demands close, periodic attention.

Sensory Observations

Even on the toughest days of the expedition, Lewis somehow found time to observe plants along the way. However, his major periods of systematic work evidently were at Fort Mandan, Fort Clatsop, and Long Camp.

The total number of specimens he collected is not known, but it is certain that all those he acquired between Fort Mandan and the Great Falls of the Missouri were destroyed when high water in the spring of 1806 flooded the underground cache where they had been stored. Some more went astray after the expedition was over; others were eventually destroyed by beetles. For many years the collection was scattered and generally ignored. Not until 1896 were most of the known sheets assembled in one collection at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and not until 1966 was it subjected to a comprehensive, detailed study.[3]That study, still a major milestone in the literature, is Paul Russell Cutright’s Lewis and Clark, Pioneering Naturalists (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969).

Also, we don’t know precisely what methods or materials Lewis used to preserve plant specimens. He might have used presses such as the one pictured here on the previous page, or else books of blotting paper and blank sheets. We do know that all the existing specimens have been remounted at some time in the past two hundred years, and that of the 226 botanical sheets now in the Lewis and Clark Herbarium at the Academy only 34 have their original labels in Lewis’s handwriting.

The process of pressing specimens preserves only the outlines, textures and skeletal structures of plants, so Lewis also took pains to write notes about their colors and tactile qualities, and often the aromas and flavors. Thus it is possible, by reading his often minutely detailed journal entries about plants, to appreciate the full scope and intensity of his concentration, the breadth of his awareness, and depth of his curiosity.

Meriwether Lewis made every step of the journey with all of his senses working all of the time. So, of course, did his co-captain and their men, so far as we can tell. The lessons of the Lewis and Clark Expedition are less about adventure, conquest, or commerce, than about concentration and awareness. These are particularly important values to cultivate in this age when most of us are artificially over-stimulated during almost every moment of our waking hours.

Related Pages

June 5, 1806

Long Camp grasses

A Nez Perce man reports that he was unable to cross the Bitterroot Mountains due to snow and toddler Jean Baptiste is given a new medical treatment. Lewis describes Long Camp area grasses and plants.

Lewis and Clark sometimes called it kinnikinnick, sometimes sacacommis. At Fort Clatsop on 29 January 1806, he described this useful plant.

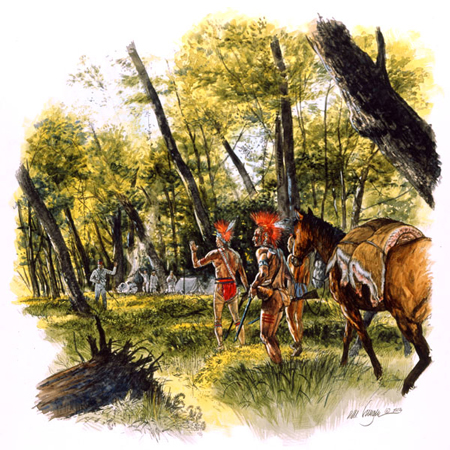

The Woodlands

Repository of plant specimens

by Catharine P. Fussell, Joseph A. Mussulman, Timothy Preston Long

Lewis sent plant specimens to William Hamilton who cultivated them in his garden at The Woodlands outside of Philadelphia.

June 16, 1806

Return to Horsesteak Meadow

On the Northern Nez Perce Trail, fallen trees slow progress while deeper and deeper snowbanks appear. They encamp where Clark had shot a stray horse last fall. Lewis prepares two plant specimens.

April 19, 1805

Grounded by winds

The wind being high, the captains decide to remain another day at their present camp below present Williston, North Dakota. Lewis describes the area’s beaver and collects a specimen of creeping juniper.

This interview with botany Professor James Reveal recorded at Packer Meadow near Lolo Pass analyzes the botany of Lewis.

July 13, 1804

Favorable winds

Favorable winds push the boats over twenty miles up the Missouri River. They encamp west of Corning, Missouri. Lewis collects a specimen of white sage, but otherwise the day appears uneventful.

June 9, 1806

Falling river, rising hopes

At Long Camp, everything is ready for tomorrow’s move to Weippe Prairie. The falling river gives hope that the mountain snows have melted, and Lewis collects a Varileaf Phacelia specimen—new to science.

September 8, 1804

Truteau's old trading house

With favorable winds, the boats make 17 miles up the Missouri. They pass Jean Baptiste Truteau’s old trading house, and they are now entirely within present South Dakota. Pvt. Shannon is still missing.

September 12, 1804

Troublesome Island

In present South Dakota, the barge nearly turns over. They then head up the wrong side of Troublesome Island and must turn back. Lewis adds two plants to his collection.

May 27, 1804

Gasconade River

The flotilla meets two trading parties coming down from Omaha and Osage villages. At evening camp near the mouth of the Gasconade River in present Missouri, arms and ammunition are inspected.

May 30, 1804

Another fourteen miles

Lost hunter Joseph Whitehouse and his boat and crew of engagés join the main group late at night. In the morning, Clark records the incident. Lewis collects a specimen of River-bank grape, Vitis riparia.

September 18, 1804

Coyote specimen

The hunters do well, so they stop early above present Chamberlain, South Dakota to jerk meat. Lewis sees the first sign of fall and makes a specimen of coyote, Missouri milkvetch, and tall blazing star.

November 16, 1805

A break in the weather

A break in the weather at Station Camp enables the main party to dry gear. Sgt. Gass reflects on reaching the end of their voyage, and Lewis adds Oregon boxleaf to his plant collection.

June 15, 1806

The Small Prairie

The men gather horses, and the expedition leaves the Weippe Prairie at 10 am. After lunch at last year’s Pheasant Camp, they continue to the Small Prairie on a slippery trail cluttered with fallen trees.

September 5, 1804

No Preserve Island

After making 13¾ miles, the boats stop early at what they name No Preserve Island to make a new cedar mast for the barge. Lewis describes the bull snake and adds two plants to his collection.

July 1, 1806

Plan to divide forces

The captains describe their plan to take different routes the Knife River villages. The Nez Perce guides agree to show Lewis the “Road to the Buffalo,” and he prepares several plant specimens.

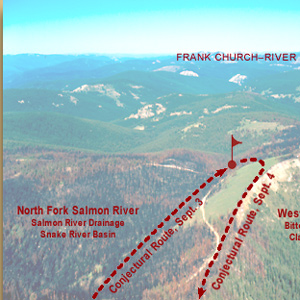

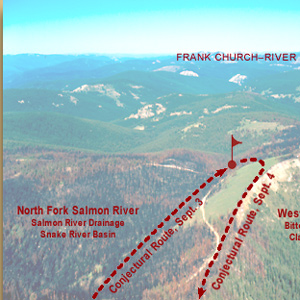

September 3, 1805

The Lost Trail

The expedition climbs the divide between the North Fork Salmon and Bitterroot Rivers near present Lost Trail Pass. In a mix of rain, snow, and sleet, they spend the night “wet hungry and cold.”

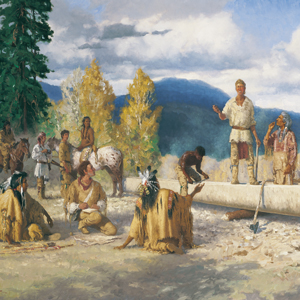

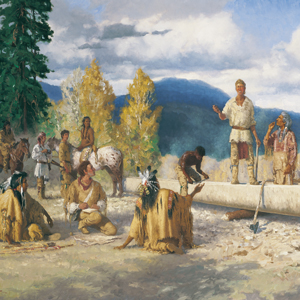

September 27, 1805

Falling trees for canoes

At the Clearwater Canoe Camp near present Orofino, Idaho, they chop down five large ponderosa pine trees and canoe-building begins. Pvt. Colter finds one of the horses lost on the Northern Nez Perce Trail.

September 2, 1805

Leaving the Indian road

Against the advice of guide Toby, they continue up the North Fork Salmon River. Without an Indian road, they pass through thick brush, a “dismal swamp” and the horses stumble crossing rocky hillsides.

Everybody liked the abundant serviceberry fruit—the Lemhi Shoshones were living on them, the enlisted men “regaled themselves,” and Lewis was the first to collect a specimen for science.

June 16, 1804

Unwanted passengers

The men use ropes to pull the barge against a current full of roiling sand making camp near present Waverly, Missouri late in the day. Clark says that the mosquitoes and ticks are numerous and bad.

August 1, 1804

A botanist's field day

At present Fort Atkinson, Nebraska, Clark prepares a peace pipe anticipating that the Otoes will soon arrive for a council. Two men search for lost horses and others search for the Otoes.

May 29, 1806

The Snake River fishery

At a village of salmon fishers, Pvt. Robert Frazer trades his razor for two Spanish dollars. At Long Camp, Lewis describes the short-horned lizard and prepares four plant specimens—all new to science.

May 25, 1804

Last 'White' village

The expedition reaches La Charrette—the last settlement of “white people on this River . . . .” Here the captains meet trader Régis Loisel who shares valuable information about where they are going.

October 4, 1804

Turn around

The day begins by dropping back three miles to a better channel. They avoid the Sioux along the banks, and camp across from an abandoned Arikara village near present Forest City, South Dakota.

Justified by the ethnobotanical record, the captains went to unusual lengths to preserve and document echinacea. Most—if not all—the Tribal Nations encountered along the Missouri River used the plant to treat snakebites in the manner described by the two captains.

This variety of the common chokecherry gave Lewis his decoction of simples and was the subject of his botanical scrutiny.

September 15, 1804

The White River

Moving up the Missouri below present Oacoma, South Dakota, the expedition passes the creek where Shannon had waited to be rescued. Gass and Reubin Field spend the night twelve miles up the White River.

April 1, 1806

Exploring the 'Quicksand' River

At Provision Camp, Pryor’s detachment explores the Quicksand River—the present Sandy in Oregon. Visiting Indians of various Nations warn of no food upriver, and no salmon for another month.

Before signing off in his last journal entry, Lewis had to botanize one last time. He concludes with an accurate description of the pin cherry, Prunus pensylvanica.

Lewis reported that a specimen of this plant “was taken the 1st of June at the mouth of the Osage River; it is known in this country by the name of the wild ginger.”

October 18, 1804

Passing the Cannonball

In passing the Cannonball River in present North Dakota, a ‘cannon ball’ is selected as a new anchor. Clark learns that most Arikaras avoid liquor, and Lewis adds prairie wild rose to his plant collection.

October 16, 1804

"Goat" hunting

The expedition struggles 14 river miles between present Fort Yates and Beaver Creek in North Dakota. Some Arikaras hunt pronghorn, and Lewis adds common poorwill and creeping juniper to his collection.

October 1, 1805

The Nez Perce method

At Clearwater Canoe Camp near present Orofino, Idaho, the men employ the Nez Perce method of hollowing out dugout canoes with fire. Lewis adds a specimen of ponderosa pine to his plant collection.

May 20, 1806

Snow and violent rains

Labiche brings in a mule deer and reports snow in the higher plains. The men have traded all their brass buttons for food, and Lewis prepares a specimen of Wilcox’s beardtongue, Penstemon wilcoxii.

June 3, 1804

Mosquitoes and ticks

At the mouth of the Osage, mosquitoes and deer ticks vex Clark, and Lewis collects a specimen of ground plum. Late in the day, the boats move up to the mouth of the Moreau east of present Jefferson City.

During the winter of 1807-1808, Pursh lived at the home of Bernard McMahon in Philadelphia. Here he worked on the drawings and descriptions of Lewis’s western plants.

Important for the history of the scientific accomplishments of the expedition, its first plant specimens were consigned to Barton’s care. Here began the disassembling of the collection, and his promised volume on natural history was never written.

July 30, 1804

Council Bluff arrival

The expedition arrives at a bluff at present Fort Atkinson, Nebraska where they intend hold a council with the Otoes. Pvt. J. Field kills a badger, and Lewis preserves it as his first zoological specimen.

August 25, 1804

Spirit Mound

The captains take a large party to explore Spirit Mound. Instead of finding its rumored devils, they suffer from excessive heat and witness birds eating swarms of flying ants.

August 10, 1804

Blackbird Hill in view

The boats sail 22½ miles up the Missouri River, and they encamp within view of Blackbird Hill. Lewis collects the earliest plant specimen that survives today, field horsetail.

May 7, 1806

Over Angel Ridge

The expedition crosses the Clearwater River and climbs present Angel Ridge where they see the “spurs” of the Rocky Mountains still covered in snow. They camp at “Musquetoe” Creek.

On 25 June 1806, on the branch of Hungery Creek where they “nooned it,” Sacagawea brought the captains “a parcel of roots” that Lewis immediately recognized as the kind Drouillard had given him ten months earlier.

June 14, 1804

Gobbling snakes

The morning is foggy as the boats leave the Grand River, and they make only eight miles up the Missouri. They meet four traders loaded with furs, and Drouillard hears snakes that gobble like turkeys.

October 2, 1804

Caution Island

Near present Willow Creek Bay, South Dakota, the expedition anticipates an attack by the Lakota Sioux, and everyone is prepared for action. Lewis adds three specimens to his plant collection.

The plant’s common names include elkhorn, ragged robin, pink fairy, and deerhorn. In the spring of 1807 Lewis turned over his plant specimens to Frederick Pursh, who gave this flower the scientific name Clarkia pulchella

Lewis collected a specimen of bitter cherry, Prunus emarginata, while at Long Camp on 29 May 1806 and described it on 7 June 1806. He wrote that “the natives count it a good fruit”.

In his journal for 12 February 1806, Lewis described the plant that now goes by the name Berberis aquifolium, which he had first noticed in the vicinity of the Cascades of the Columbia River, about 145 miles from the ocean.

June 12, 1806

The beautiful Weippe Prairie

At Weippe Prairie in present Idaho, the expedition waits for the Bitterroot Mountain snow to melt. The warmer weather brings mosquitoes and camas blooms. Lewis collects two more plant specimens.

June 10, 1806

Leaving Long Camp

After a nearly 6-week stay at Long Camp waiting for mountain snows to melt, the expedition travels to the “quawmash flatts”—Weippe Prairie, Idaho. Lewis botanizes and taste-tests Columbian ground squirrel.

Because it appears in the Rockies at the edges of receding snowbanks it has also earned the name glacier lily. Lewis’s specimen, collected 15 June 1806 on the Clearwater River, was the one used by Pursh to describe the species.

July 15, 1804

Treeless plains

After waiting for the Missouri River fog to lift, the expedition sets out at 7 am and encamps near present Nemaha, Nebraska. Lewis’s chronometer stops, and he collects a specimen of hedge bindweed.

May 10, 1804

First plant specimen

At winter camp on the present Wood River in Illinois, the enlisted men are ordered to carry 100 lead balls for their rifles. In St. Louis, Lewis collects the expedition’s first plant specimen.

May 22, 1804

Trading with Kickapoo hunters

After a very rainy night, the expedition sets out at 6 am, travels 18 miles, and camps near the mouth of the Femme Osage River in present-day Missouri. They trade with some Kickapoos for four deer.

August 17, 1804

Otoe chiefs and a deserter

At Fish Camp near present Homer, Nebraska Pvt. Labiche informs the captains that three Otoe chiefs and the deserter Pvt. Reed will soon arrive. A prairie fire is set as a signal to any nearby Indians.

There is a great abundance of a species of bear-grass which grows on every part of these mountains,” wrote Lewis on 15 June 1806. “It’s growth is luxouriant and continues green all winter but the horses will not eat it.”

June 1, 1804

Mouth of the Osage

After a hard day, the expedition stops at the mouth of Osage River where the captains make celestial observations late into the night. Lewis also collects a specimen of wild ginger, Asarum canadense.

April 16, 1806

"Great Mart of all this Country"

Clark crosses the river to trade for horses and calls The Dalles of the Columbia the “Great Mart of all this Country.” At Fort Rock, the men make saddles, Lewis botanizes, and Cruzatte plays the fiddle.

August 4, 1804

Moses Reed is missing

The expedition travels 15 miles and encamps southwest of present Modale, Iowa. The captains record yesterday’s speech to the Otoes, and Pvt. Moses Reed, who left to retrieve his knife, does not return.

May 8, 1806

An argument about horses

On the Camas plains high above the Clearwater River, Twisted Hair and Cutnose argue about the expedition’s horses. Lewis describes the Nez Perce methods of extracting foods from the ponderosa pine.

June 25, 1806

Jerusalem Artichoke Camp

The expedition follows the Northern Nez Perce Trail to Hungery Creek. The captains fear the Nez Perce guides have left them, and Sacagawea gathers roots resembling the Jerusalem artichoke.

“The prickly pear is now in full blume,” he wrote on a mild early-summer day in 1805, “and forms one of the beauties as well as the greatest pests of the plains.”

November 17, 1805

A disappointing cape

At Station Camp, Clark trades with some Chinooks and gathers volunteers to visit the Pacific Ocean tomorrow. Lewis returns from Cape Disappointment without finding any ships.

July 18, 1804

Geology and botany

Clark remarks on the region’s geology and Lewis collects a partridge pea specimen as they travel up the Missouri below present Nebraska City. At their evening camp, a stray Indian dog is fed.

July 9, 1805

Sinking the iron-framed boat

The iron-framed boat is too leaky, and it is intentionally sunk. The captains plan to build two new dugout canoes, and Lewis collects a specimen of blue flax—new to science and a namesake species.

May 17, 1806

Lewis's wet chronometer

After a wet night, the day continues with rain at Long Camp and snow in the hills at present Kamiah, Idaho. Lewis prepares a lily plant specimen, and they hope to cross the Rocky Mountains soon.

September 21, 1804

Camp washes away

At the Big Bend of the Missouri, the men barely escape as the sandbar they are camping on washes into the river. They continue up the Missouri camping near present Joe Creek Bay, South Dakota.

August 27, 1804

Yankton Sioux visitors

Reaching present Yankton, South Dakota, they set a fire to signal the Sioux to a council. A Yankton man and two boys arrive. Drouillard fails to find Pvt. Shannon who hasn’t returned from a hunting trip.

July 20, 1804

Drouillard is sick

The expedition passes Water-which-Cries and Waubonsie creeks along the present Nebraska and Iowa border. Lead hunter George Drouillard is sick, and Lewis collects two specimens of clover.

November 1, 1805

A day with the Watlalas

Most of the men move baggage and canoes around the Cascades of the Columbia. Clark describes the Upper Chinookan Watlala People living in the area, and Lewis adds Pacific madrone to his plant collection.

July 27, 1804

Leaving White Catfish Camp

At White Catfish Camp, the boats are loaded, and they proceed to present Lewis and Clark Landing in Omaha, Nebraska. A knee is cut, mosquitoes rage, and Lewis adds several plants to his collection.

Lewis collected buffaloberry specimens which were new to science and Clark had them in a delightful tart. Native Americans had been eating the bright red berries for generations.

April 12, 1805

Little Missouri River

Early in the day, a crumbling bank threatens the red pirogue. They spend most of the day at the Little Missouri River and see beaver, empty Assiniboine camps, creeping juniper, and wild onions.

The day Sacagawea gathered Indian breadroot, Lewis wrote a detailed ethnobotanical description. The specimen he prepared a year prior is now used as the primary identifier of the species.

Columbia plateau biscuitroots: “one of the grateful vegetables” by naturalist Jack Nisbet. An Indian food source for thousands of years.

September 2, 1804

Passing Bon Homme Island

Below present Springfield, South Dakota, the boats navigate around a large island with numerous elk. They describe unusual sand ridges which appear as Indian fortifications, and Lewis collects plants.

January 20, 1806

Five plant specimens

At Fort Clatsop, Lewis prepares five new plant specimens and describes roots eaten by local Chinookan Peoples. The captains worry about the rate at which they are going through their supply of elk.

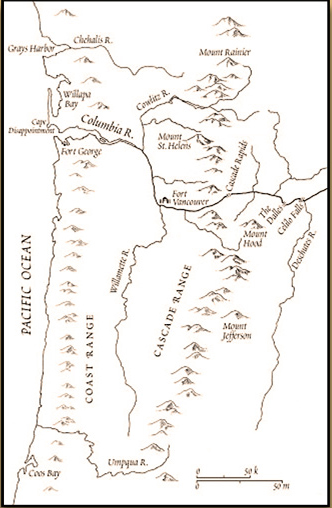

Douglas recognized landmarks from Vancouver’s and William Clark’s maps as soon as he sighted Cape Disappointment at the Columbia River’s fearsome bar. The collector continued to name familiar sentinels as he moved inland including “Mount Jefferson of Lewis and Clarke.”

April 14, 1806

Romantic scenes

In a calm stretch below present Lyle, Washington, Lewis enjoys romantic scenes and a drier climatic zone; and he prepares four plant specimens. The captains are encouraged to see residents with horses.

April 15, 1806

Return to Fort Rock

While paddling up the Columbia, the 33 members see many horses but are unsuccessful in trading for any. They encamp at Fort Rock at present The Dalles, Oregon. Lewis prepares four plant specimens.

The Academy’s monumental collection of scientific specimens includes the Lewis and Clark Herbarium, consisting of most of the botanical specimens the Expedition brought back East.

September 19, 1804

The Sioux Pass

The winds are favorable and the hunting good. Clark explores the Sioux Pass of the Three Rivers, and Lewis adds broom snake weed to his plant collection. Camp is near present Lower Brule, South Dakota.

Its oak-strong, hickory-tough wood made powerful, reliable hunting bows. Early French explorers and traders translated its Indian name into bois d’arc,–”wood for a bow,” which was easily anglicized into “bodark.”

August 27, 1806

Hunting on the Big Bend

While passing through the Big Bend of the Missouri, the expedition nearly runs out of meat. They hear bison bellowing and stop to hunt. Lewis collects a plant specimen, but aggravates his gunshot wound.

William Clark, pushing on in advance of the hungry men of the Corps, came upon two adjacent Indian villages totaling about 30 lodges on Weippe Prairie. They gave him and his six hunters “roots in different States, Some round and much like an onion which they call quamash.”

William Clark first mentioned the root cous on 1 November 1805, saying that native people living near the future Bonneville Dam site traded beads to obtain it from people up the Columbia River. To Clark, it was “cha-pel-el bread.”

August 10, 1806

Sketches of River Rochejhone

Lewis has the boats repaired while he botanizes. In the afternoon, they move a few miles closer to Clark’s camp near present Tobacco Garden, North Dakota. There, Clark works on his maps of the Yellowstone.

September 4, 1804

Shannon still missing

They pass an old Ponca village and make eight miles before stopping at the Niobrara River to explore, hunt, and look for signs of Pvt. Shannon who has been missing several days.

August 2, 1804

The Otoes arrive

At sunset near present Fort Atkinson, Nebraska, several Otoes arrive at Council Bluff. Guns are fired and hands shaken. Lewis collects a specimen of snowberry or buckbrush and examines a great egret.

May 29, 1804

A lost hunter

The expedition spends most of the day at the mouth of the Gasconade River drying goods and waiting for Joseph Whitehouse to return from a hunting trip. Lewis prepares a plant specimen of Golden Seal.

October 1, 1804

The Cheyenne River

At the Cheyenne River, the captains meet trader Jean Vallé who tells them about that river. Clark finds that buffaberries make a delightful tart, and Lewis adds three specimens to his plant collection.

Flathead Salish, Kutenai, Shoshoni, and Nez Perce people all regard the bitterroot with solemn reverence. No other root may be harvested until the elder women of the tribe have conducted the annual First Roots ceremony.

June 1, 1806

Clarkia and rough wallflower

Clark mentions a plan to divide forces after reaching Travelers Rest, and Drouillard is sent to find Nez Perce men to guide them. Lewis discusses the Clarkia flower and prepares two more plant specimens.

September 1, 1804

Leaving Calumet Bluff

The expedition leaves the Yankton Sioux and reaches Bon Homme island, now inundated behind Point Gavins Dam. Several catfish are caught, and Lewis collects a specimen of wild four-o’clock.

May 6, 1806

Three Coeur d'Alenes

The expedition spends most of the day at the Potlatch River—their Colter’s Creek. Lewis meets three Coeur d’Alene Indians, and Clark gives medical aid. They eventually move to another Nez Perce village.

October 3, 1804

Mice problems

The captains discover that mice are eating their corn, paper, and cloth. Lewis adds pasture sagewort and long-leaved sagewort to his plant collection, and they camp near present Sutton Bay in South Dakota.

Lewis mentioned two species of tobacco, possibly Nicotiana quadrivalvis and N. rustica—a Mexican species called Aztec tobacco—that the Arikara cultivated.

Notes

| ↑1 | Jackson, Letters, passim. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | It is estimated that seventy or seventy-five specimens were new to science when Lewis collected them. Pursh honored Lewis by naming four new species after him: Linum lewisii (LEE-noom loo-WEE-see-eye; Lewis’s wild flax), Mimulus lewisii (MIM-oo-luss loo-WEE-see-eye; Lewis’s monkey flower), Philadelphus lewisii (fill-uh-DELL-fuss loo-WEE-see-eye; Lewis’s syringa–si-RING-guh); and Lewisia rediviva (reh-dee-VEE-vuh; bitterroot). |

| ↑3 | That study, still a major milestone in the literature, is Paul Russell Cutright’s Lewis and Clark, Pioneering Naturalists (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.