The American Elk

In his letter of instruction to Meriwether Lewis as he prepared to cross the continent with the Corps of Discovery, Thomas Jefferson told him to observe “the animals of the country generally, and especially those not known in the U.S.”[1]Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1904–5), 7:249. As a result, the Lewis and Clark journals contain the first reliable documentation of wildlife in the drainages of the Missouri and Columbia rivers.

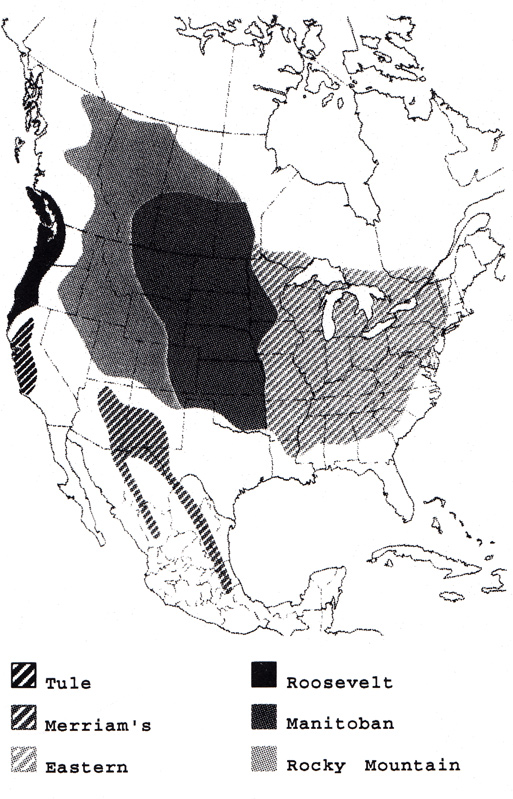

One of the animals recorded by Lewis and Clark—and which became one of the staples of their mostly carnivorous diet—was the wapiti, or American elk (Cervus elaphus). Wildlife biologists have estimated that before European settlement the continent may have supported an elk population of 10 million.[2]Jack Lyon and Jack Ward Thomas, “Elk: Rocky Mountain Majesty,” Restoring America’s Wildlife (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, 1987), 145–159. In precolonial times this large member of the deer family, although now associated almost exclusively with the Rocky Mountains, was abundant on the plains and ranged as far east as the woodlands of Pennsylvania and New York and south to Georgia.[3]Peter Matthiessen, Wildlife in America (New York: Viking Press, 1959), 62. The Corps of Discovery encountered four of the six subspecies—the Eastern, Manitoban (plains), Rocky Mountain, and Roosevelt (Northwest coastal) elk.[4]Larry D. Bryant and Chris Maser, “Classification and Distribution of North American Elk: Ecology and Management,” Wildlife Management Institute (Harrisburg: Stackpole Books, 1982), 1–60.

An English sea captain, George Waymouth, reported sighting “Olkes,” or elk, on his voyage to Virginia in 1605.[5]Ernest Thompson Seton, The Life Histories of Northern Animals (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1909), 41. The American elk’s European counterpart and close relation is the red deer, but the animal Europeans call an elk is in fact what Americans call a moose. There is no evidence, however, that moose in post-glacial times ever ranged as far south as Virginia. Waymouth probably applied the name indiscriminately to any big, large-racked member of the deer family. Perhaps to avoid such confusion, in 1806 the naturalist Benjamin Smith Barton gave it the species name wapiti, a term he borrowed from the Shawnees, in whose language it means “light rump.”[6]John B. Kirsch and Kenneth R. Greer, Bibliography: Wapiti and European Red Deer (Montana Fish and Game Department, Game Management Division, Special Report No. 2, 1968), 1; Robert M. McClung, Lost … Continue reading Barton was one of the scientists who advised Lewis during his pre-expedition visit to Philadelphia in the spring of 1803, but it’s not known whether he urged the explorer to use the term wapiti in his recorded observations. If Barton did, Lewis ignored him—the journals of both Lewis and Clark refer only to elk.

The expedition left Camp Wood, near St. Louis, on 14 May 1804. About a month later, on June 17, when it had reached present-day Carol County, Missouri, Lewis described a country abounding in “Bear Deer & Elk.”[7]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), 2:306. All quotations or references to journal entries in the ensuing text are from … Continue reading Clark mentioned sighting elk on 12 July 1804, when the expedition was in Richardson County, Nebraska, and two days later Patrick Gass wrote that they “saw some elk, but could not kill any.” Their luck changed on 1 August 1804 in Washington County, Nebraska, a few miles north of present-day Omaha: “3 Deer & an Elk Killed to day,” Clark reported. It was his 34th birthday, and to celebrate he ordered a dinner of venison, beaver tail, and “an Elk fleece,” topped off with a dessert of wild fruits.

Selected Encounters

the party killed several deer and some Elk principally for the benefit of their skins which are necessary to them for claothing.

—Lewis, 13 May 1805

our ropes are but slender, all of them except one being made of Elk’s skins, and much woarn, frequently wet and exposed to the heat of the weather are weak and rotten.

—Lewis, 28 May 1805

It was by means of a cordelle or “chord”—a heavy tow rope made of elk hides—that allowed the boats to be hauled upstream by the men pulling them along the shore.

Several men employed in Haveing & Graneing Elk hides for the Iron boat as it is called.

—Clark, 21 June 1805

the men have provided themselves verry amply with mockersons & leather clothing.

—Lewis, 23 February 1806

Gass reported that they made 338 pairs of moccasins. “This stock,” he emphasized, “was not provided without great labor, as the most of them are made of the skins of elk.”

Sergt. Gass returned with the flesh of eight elk and seven skins . . . we had the skins divided among the messes in order that they might be prepared for covering our baggage when we set out in the spring.

—Lewis, 19 February 1806

This morning early the flesh of the remaining Elk was brought in . . . we employed the party in drying the meat today which we completed by the evening and we had it secured in dryed Elkskins and put on board in readiness for an early departure.

—Lewis, 7 April 1806

Summary of Elk Kills

| Dates | Location | No. Killed |

|---|---|---|

| 14 May 1804–6 April 1805 | Wood River to Fort Mandan | 94 |

| 7 April–26 April 1805 | Fort Mandan to Yellowstone River | 8 |

| 27 April–13 September 1805 | MT-ND border to Lolo Pass | 81 |

| 1 December 1805–20 March 1806 | Mouth of the Columbia | 131 |

| 23 March 1806–29 June 1806 | Fort Clatsop to Lolo Pass | 20 |

| 30 June 1086–3 August 1806 | Lolo Pass to MT-ND border | 36 |

| 4 August 1806–21 September 1806 | MT-ND border to St. Louis | 26 |

| Total Elk Killed | 396 | |

Elk Distribution Then and Now

Precolonial Elk Distribution

Larry D. Bryant and Chris Maser, “Classification and Distribution of North American Elk: Ecology and Management, Wildlife Management Institute.

Precolonial distribution of the six subspecies of American elk. Lewis and Clark encountered the Eastern, Manitoban, Rocky Mountain, and Roosevelt subspecies. The other two subspecies are Merriam’s elk and the Tule elk.

When Lewis and Clark crossed the continent two centuries ago they found elk abundant on the plains and scarce in the mountains—exactly the opposite distribution we find today. Biologists have long debated whether the elk’s “natural” habitat is mainly plains or woodland; some have argued that elk were predominantly creatures of the plains which retreated to the protection of higher, timbered lands after European settlers usurped their traditional range.

In fact, elk thrive in both plains and woodland environments and were always at home in the latter. As Lewis observed, “They [elk] are common to every part of this country, as well as the timbered lands as the plains, but they are much more abundant in the former than the latter.”[8]Elliott Coues, History of the Expedition Under the Command of Lewis and Clark (New York: Dover Publications, 1965; re-print of 1893 edition), 3:845. According to the naturalist Olaus J. Murie, “There is much evidence to show that in early times the elk were more generally a dweller of woodlands and mountains than has been supposed . . . . [I]t may be safely concluded that the elk have always been at home in the mountains as well as on the plains.”[9]Olaus J. Murie, The Elk of North America (Harrisburg, Penn.: Stackpole Co., 1951), 47–48. A survey of early accounts of Montana makes it clear that elk were present throughout the mountains before the region was widely settled.[10]Craig S. and Pamela R. Knowles, A Bibliography of Literature and Papers Pertaining to Pre-settlement Wildlife and Habitat on Montana and Adjacent Areas (Missoula, Montana: U.S. Forest Service, 1993).

In the Rocky Mountains, differences in slope, aspect to the sun, and elevation multiply the diversity and abundance of plants, thus providing a wide range of feeding opportunities for elk. Wildlife biologists and experienced hunters know that weather conditions in mountain country play an important role in determining elk concentrations. They also know that temperature and precipitation in one year affect elk forage in the next. All of these factors must be considered when asking why Lewis and Clark saw so few elk in the mountain valleys of the Jefferson, Beaverhead, Bitterroot, and upper Snake rivers, but fundamentally the reason seems clear enough. Elk would have congregated in the valleys during the late fall, winter, and early spring. But the outbound Corps of Discovery traversed the valleys in late summer, when elk were still on their feeding grounds in the higher alpine meadows.

Montana 1805: An American Serengeti

After wintering at Fort Mandan, in North Dakota, the expedition headed west up the Missouri in the spring of 1805. On April 27 it entered Montana, where Clark observed “great numbers of Goats or antilopes, Elk, Swan Gees & Ducks” although “no buffalow to day.” His gaze took in one of the richest gamelands in the world. Next to the buffalo, or American bison, the largest ungulate in that vast landscape was the wapiti: a mature buck elk can stand over five feet tall and weigh more than 600 pounds.[11]Herbert S. Zim and Donald F. Hoffmeister, Mammals: A Guide to Familiar American Species (New York: Golden Press, 1955), 136.

During the Montana portions of the expedition, the journals mention elk 95 times (65 on the outbound leg and 30 homeward bound). Most of the entries are passing references to sightings or kills, but they also discuss habitat, grazing patterns, antler development, and the use of elk hides for making clothes, moccasins, and tow ropes. Elk hides were also used to make the skin of Lewis’s iron-framed boat, his ill-conceived experiment at the Great Falls of the Missouri.

The expedition’s hunters killed at least 117 elk in Montana, some 40 percent of them east of the mountains, in Chouteau and Cascade counties, (See table, page 31, for a summary of the 396 total elk killed over the course of the expedition.)[12]Harvest numbers should be regarded as minimum, since the various journals differ on dates and numbers of elk killed. Some entries refer to bucks killed, without stating whether the animal was a deer … Continue reading The great majority of Montana kills occurred on the plains. Few elk, in fact, were observed in the mountains west of the Three Forks, which the outbound Corps of Discovery reached on 25 July 1805, and no elk were killed from 7 August through 6 September, when the expedition ventured deeper into the Rockies. The hunters shot their last elk in Montana on September 7 in the vicinity of Grantsdale, in the Bitterroot Valley, west of the Continental Divide.

The explorers left Montana on 13 September 1805 and did not mention elk again until 13 November 1805, when Clark noted “Elk Sign,” presumably meaning tracks, which he spotted at Point Ellice, on the north shore of the Columbia estuary. During the Corps’s cold, wet, and thoroughly miserable winter at Fort Clatsop, elk probably made the difference in survival. Between 1 December 1805, and 20 March 1806, according to Gass, hunters brought in 131. The winter meat was lean and tough, but it helped to keep them alive.[13]Gass’s entry of March 20, 1806. Moulton, 10:199. See on this site Fort Clatsop Elk.

War Zones and Sinks

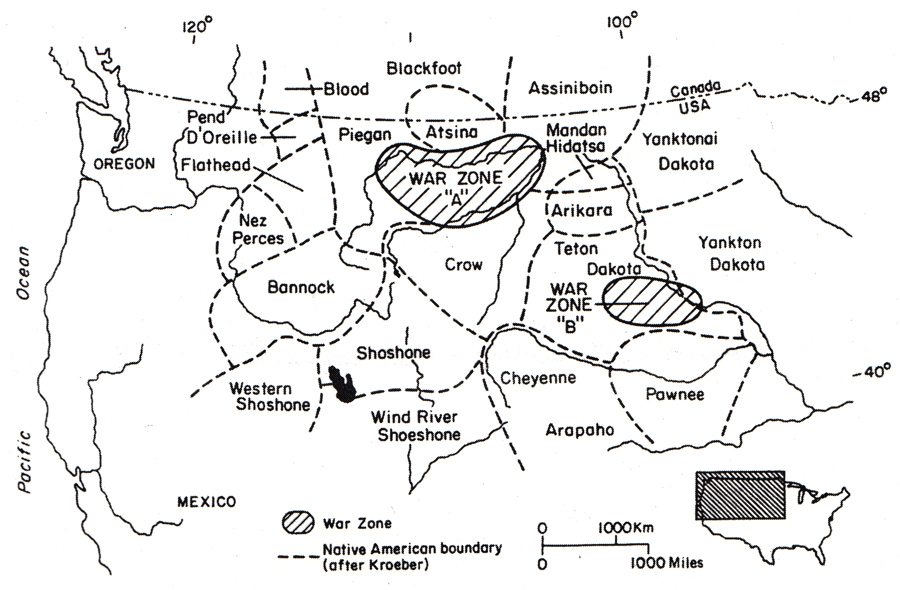

Distribution of Plateau and Plains Indians

From Paul S. Martin and Christine R. Szuter, “War Zones and Game Sinks In Lewis And Clark’s West,” Conservation Biology, February 1999.

Distribution of Plains Indians and their neighbors around the upper Missouri war zones from the mouth of the Yellowstone to Great Falls (War Zone A) and between the White and Niobrara rivers (War Zone B).

Another reason has to do with the relationship between warring Indians and the abundance of game. Lewis and Clark found more elk in the headlands above the mouth of the Columbia; still, they were few in number compared to the many they had encountered on the plains of Montana. Why? Hypotheses include differences in habitat and hunting pressures by local tribes. A recent study by ecologists Paul S. Martin and Christine R. Szuter, “War Zones and Game Sinks in Lewis and Clark’s West,” sheds light on the possible role of Indian hunters in explaining this difference.[14]Paul S. Martin and Christine R. Szuter, “War Zones and Game Sinks in Lewis and Clark’s West,” Conservation Biology, 13 no. 1 (February 1999): 36–45.

In Martin and Szuter’s parlance, a “war zone” is a buffer or neutral area between warring tribes living on its perimeter—war parties might penetrate the zone to skirmish but do not occupy it permanently, and the absence of resident hunters allows game to flourish. By contrast, a “game sink” is an area occupied by numerous resident hunters, resulting in a scarcity of game.

Martin and Szuter argue that the upper Missouri constituted a huge war zone, stretching over 120,000 square kilometers, from the mouth of the Yellowstone west to the Three Forks and encompassing the entire region between the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. To a great extent this vast area served as a buffer between the tribes living on its eastern, southern, and western fringes and the aggressive Blackeet to the north. As Clark himself astutely noted on 29 August 1806, “I have observed that in the country between the nations which are at war with each other the greatest numbers of wild animals are to be found.” The absence of human hunters would account not only for the abundance of game but (as noted earlier) for its tameness.

The Columbia corridor—a game sink—offered a striking contrast; in Lewis’s estimate it held a permanent population of 80,000 Indians whose hunting pressure significantly depressed the number of large game animals.[15]Ibid. In effect, the outbound Corps of Discovery found itself in a game sink during its time in the Columbia watershed and while traversing the mountains east of the Continental Divide.

As an experienced hunter, Lewis knew the importance of different kinds of forage to the health and abundance of game animals. In North Dakota and Montana he noted elk feeding on sagebrush and willow. At Fort Clatsop on 4 February 1806, he observed that elk grazing on still-green grass and rushes in open areas are “in much better order” than those foraging in “woody country” where their food is “huckle berry bushes, fern, and an evergreen shrub which resembles the lorel.”

Elk are generalists when it comes to feeding. One study has shown that Rocky Mountain elk graze on at least 142 species of forbs, ferns, and lichens as well as 77 species of grass and grasslike species, and browse on 111 species of shrubs and trees.[16]Ibid. Elks’ ability to subsist on such a variety of plants contributed to their wide range, and their occurrence along most of Lewis and Clark’s route was important to the expedition’s success. Wapiti (to use Barton’s preferred name) provided food and clothing, and as Stephen Ambrose has noted, “the cord that bound body and soul together at Fort Clatsop was made of elk.”[17]Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), p. 322.

Elkhorn Steeples

Elkhorn Pyramid on the Upper Missouri

by Karl Bodmer (1809–1867)

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Die Elkhorn-Pyramide am obern Missouri. La pyramide des cornes d’elk sur le haut Missouri. The elkhorn pyramid on the upper Missouri.”[18]New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 31 October 2019. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c404-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Surprisingly, there is no mention in the journals of several unusual sites—towering mounds of elk antlers—discovered by later explorers of the upper Missouri. In 1832, Prince Maximilian of Wied recorded, 17 miles downstream from the mouth of the Judith River, an “Elkhorn Steeple” 18 feet high, with a base of 15 feet. Karl Bodmer, the artist accompanying the prince, sketched the steeple (opposite).[19]Maximilian of Wied, Travels in the Interior of North America, 1832-1834 (Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1906; English translation, originally published in 1843). In 1854, ethnographer Edwin T. Denig reported “an immense pile of elk horns that . . . must be very ancient” on the south side of the Missouri River, 50 miles above the mouth of the Yellowstone.[20]Edwin T. Denig, “Indian Tribes of the Upper Missouri,” 46th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1928-1929, J.N.B. Hewitt, ed. (Washington, D.C., 1930), 375-628. The so-called Elkhorn Monuments, according to James H. Bradley, “are among the mysteries of the west never to be unraveled. . . . They contained many thousand horns . . . and appeared to have been built [up over] a good many years, as the horns were somewhat decayed and the superincumbent weight had pressed the base of each mound several inches into the prairie soil. . . . There is nothing to indicate the purpose of the monuments which remain wrapped in as deep mystery as their origin.” Bradley states that the elkhorn monuments were “taken down by the American Fur Company in 1850 and the best horns selected and carried to St. Louis in the hope they would find a ready sale.”[21]James H. Bradley, Contributions to the Historical Society of Montana (Boston: J. S. Canner and Co., 1966) 9:349-350.

Notes

| ↑1 | Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1904–5), 7:249. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jack Lyon and Jack Ward Thomas, “Elk: Rocky Mountain Majesty,” Restoring America’s Wildlife (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, 1987), 145–159. |

| ↑3 | Peter Matthiessen, Wildlife in America (New York: Viking Press, 1959), 62. |

| ↑4 | Larry D. Bryant and Chris Maser, “Classification and Distribution of North American Elk: Ecology and Management,” Wildlife Management Institute (Harrisburg: Stackpole Books, 1982), 1–60. |

| ↑5 | Ernest Thompson Seton, The Life Histories of Northern Animals (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1909), 41. |

| ↑6 | John B. Kirsch and Kenneth R. Greer, Bibliography: Wapiti and European Red Deer (Montana Fish and Game Department, Game Management Division, Special Report No. 2, 1968), 1; Robert M. McClung, Lost Wild America: The Story of Our Extinct and Vanishing Wild Life (Hamden, Connecticut: Linnet Books, 1993), 52–53. |

| ↑7 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), 2:306. All quotations or references to journal entries in the ensuing text are from Moulton, Vols. 2–11, by date, unless otherwise indicated. Moulton, citing E. Raymond Hall, The Mammals of North America (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1981), 2:1084–86, states the explorers “did not actually see an elk until July 14,” referring to an entry in the journal of Patrick Gass. But this is arguable, since the region’s tall-grass prairies and wooden bottomlands would certainly have supported elk. |

| ↑8 | Elliott Coues, History of the Expedition Under the Command of Lewis and Clark (New York: Dover Publications, 1965; re-print of 1893 edition), 3:845. |

| ↑9 | Olaus J. Murie, The Elk of North America (Harrisburg, Penn.: Stackpole Co., 1951), 47–48. |

| ↑10 | Craig S. and Pamela R. Knowles, A Bibliography of Literature and Papers Pertaining to Pre-settlement Wildlife and Habitat on Montana and Adjacent Areas (Missoula, Montana: U.S. Forest Service, 1993). |

| ↑11 | Herbert S. Zim and Donald F. Hoffmeister, Mammals: A Guide to Familiar American Species (New York: Golden Press, 1955), 136. |

| ↑12 | Harvest numbers should be regarded as minimum, since the various journals differ on dates and numbers of elk killed. Some entries refer to bucks killed, without stating whether the animal was a deer or elk. |

| ↑13 | Gass’s entry of March 20, 1806. Moulton, 10:199. See on this site Fort Clatsop Elk. |

| ↑14 | Paul S. Martin and Christine R. Szuter, “War Zones and Game Sinks in Lewis and Clark’s West,” Conservation Biology, 13 no. 1 (February 1999): 36–45. |

| ↑15 | Ibid. |

| ↑16 | Ibid. |

| ↑17 | Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), p. 322. |

| ↑18 | New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 31 October 2019. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c404-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

| ↑19 | Maximilian of Wied, Travels in the Interior of North America, 1832-1834 (Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1906; English translation, originally published in 1843). |

| ↑20 | Edwin T. Denig, “Indian Tribes of the Upper Missouri,” 46th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1928-1929, J.N.B. Hewitt, ed. (Washington, D.C., 1930), 375-628. |

| ↑21 | James H. Bradley, Contributions to the Historical Society of Montana (Boston: J. S. Canner and Co., 1966) 9:349-350. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.