President Jefferson directed Lewis to observe seasonal transitions as marked by the “times of appearance of particular birds, reptiles or insects.” That made bugs were worthy of notice.

We should not be childishly disgusted

at the examination of the less valuable animals.

For in all natural things there is something marvelous.

Jefferson’s Orders

The daily remarks for 7 April 1806 record: “the air temperate, birds singing, the pizmire, flies, beetles in motion.”

Pizmire, or pis-mire–pissant in the U.S.—was the 14th-century name for the insect universally known today as the wood ant. In Chaucer’s time it arose from the fact that this insect’s home, or anthill, smells like the formic acid that comprises its venom; they both are redolent of urine. F. rufa is among the larger ants, often reaching 10 mm (0.4 in). If challenged or otherwise alarmed, it is capable of squirting formic acid several feet from its acidopore.

With a step downward into social commentary, if not vulgarity, pismire, the centuries-old common English epithet for this species soon entered slang as a synonym for any insignificant but annoying human busybody. The generic name for the wood ant is the Latin noun Formica, similarly derived from the formic acid that this genus excretes for both offensive and defensive purposes. (The brand name Formica, denoting the familiar heat resistant plastic laminate has an entirely different etymology and meaning.) The specific epithet rufa is Latin for “red.” Dome-shaped nests of Formica rufa, most often found in small but sunny forest clearings, can be as high as 2 meters (78 inches).

On 25 August 1804, Gass described the annoying insects on today’s Spirit Mound as “some Stone piss ants.”

Captain Lewis’s orders from President Jefferson, his commander-in-chief, contained three basic, imperative injunctions. That is, the principal objectives of the expedition, were: First, “to explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream[s] of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean, . . . may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.” Second, “[t]he interesting points of the portage between the heads of the Missouri, & of the water offering the best communication with the Pacific ocean, should also be fixed by [celestial] observation.” Third, “[C]onsidering the interest which every nation has in extending & strengthening the authority of reason & justice among the people around them, it will be useful to acquire what knolege you can of the state of morality, religion, & information among them; as it may better enable those who man endeavor to civilize & instruct them, to adapt their measures to the existing notions & practices of those on whom they are to operate.”

Jefferson then listed six more “objects worthy of notice,” including “the animals of the country generally, & especially those not known in the U.S.” That direction tacitly included the huge phylum known as arthropods–one of today’s 35 different classes of animals–which identifies the invertebrates that fall into the scientific classification containing the more than 1,134,000 species we currently call insects. More specifically, under the same rubric the President directed Lewis to observe seasonal transitions as they are marked by the “times of appearance of particular birds, reptiles or insects.” [2]Donald D. Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents 1783–1854 (Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1978), 63. Lewis himself was especially conscientious in his observance of that last directive, and so was Clark. In turn they must have ordered all members of the Corps to keep their eyes open, and they all–at least all the journalists–did so now and then, right down to Clark’s servant and slave, York.

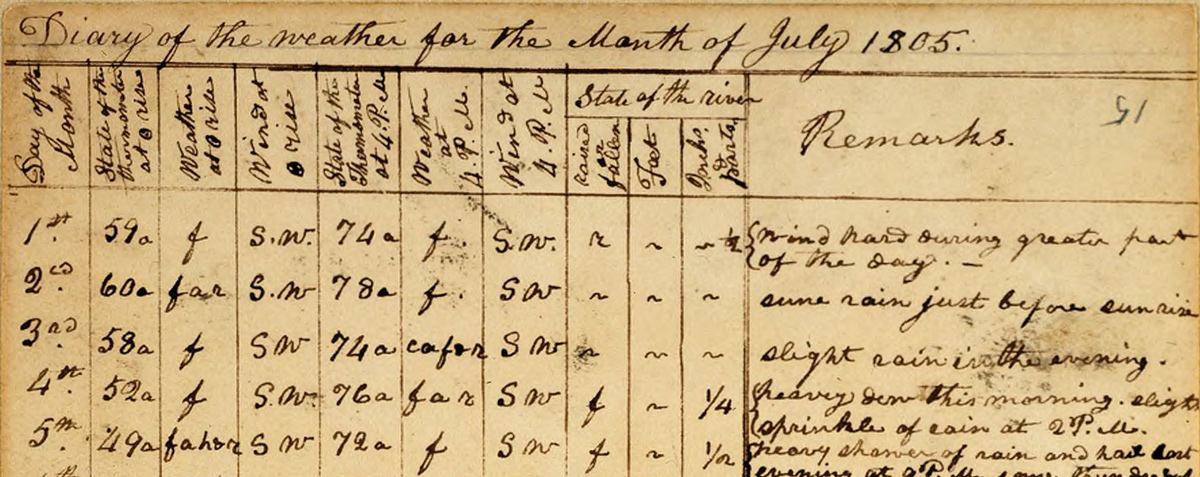

Weather Remarks

“Diary of the Weather for the month of July 1805” (Detail)

© American Philosophical Society, FE-015.

On 1 January 1804, the captains explained the intended purpose of the “Remarks” column in the monthly weather summaries:

In the miscellanious column or column of remarks are noted, the appearance quantity and thickness of the floating or stationary ice, the appearance and quantity of drift-wood, . . . the appearance of birds, reptiles and insects, in the spring disappearance in the fall, leafing flowering and seeding of plants, fall of leaf, access and recess of frost, debth of snows, their duration or disappearance.

Most of the expedition’s journalists mentioned insects from time to time, but only in very general ways—as harbingers of seasonal changes, for example. Meriwether Lewis seldom took time to study any of them with the close attention he often gave to plants, birds, mammals, or even reptiles and fish. From Fort Mandan he sent back to President Jefferson “1 Tin box, containing insects mice &c.,” without further details so far as can be known now. Undoubtedly he expected that Jefferson would forward them to a suitably qualified expert such as Benjamin Smith Barton or Charles Willson Peale, who would sort them out and perhaps write scientific descriptions of them. Peale’s collection, as of 1810, numbered about 4,000 specimens.

Logically enough, notations relating to the change of seasons found their places in the end-of-month lists of daily records of weather and random “Remarks,” as well as now and then in daily journal entries. On 27 March 1805, for instance, we read that the first insect Lewis saw this day was “a large black knat”; that’s all he wrote. Not even a clue as to what he meant by “large.” No single insect, no matter the color or kind, could serve as a harbinger of spring, but it . On 9 April 1805 he recorded: “the Musquitoes revisit us, saw several of them.” Certainly, those kinds of remarks served their intended seasonal measurements, but they tell us nothing else about the species themselves, such as their identifying biological features that could have served as bases for comparisons, and as stimuli for future explorers to look a little closer. But very few of the journalists’ remarks on insects are much more inspiring than—in the weather summary for 29 March 1805—”a variety of insects make their appearance, as flies bugs &c.”

Sandy River Observations

Near Oregon’s Quicksand (now Sandy) River, two weeks out of Fort Clatsop on their homeward journey, Lewis concluded his journal entry for 5 April 1806 with the observation that “the mellow bug and long leged spider have appeared, as have also the butterfly[,] blowing fly and many other insects. I observe not any among them which appear to differ from those of our country or which deserve particular notice.” He was still in the heart of flea country, but he didn’t mention them.

As an afterthought, however, he added two more heralds of spring: “the tick has made it’s appearance it is the Same with those of the Atlantic States. the Musquetoes have also appeared, but are not yet troublesome.”

There is considerable ambiguity regarding the true identity of Lewis’s “mellow bug.” He may have meant the melon bug of the family Chrysomelidae, commonly called leaf beetle.[3]Lorus and Margery Milne, National Audubon Society Guide to North American Insects & Spiders (New York: Knopf, 1980), 603. He may have meant “melon bug,” but that doesn’t help us much either. Alternatively, it could have been a melon aphid, Aphis gossypii Gover; also known as the cotton aphid; a melon fly, Bactrocera cucurbitae (Coquillett); melon thrips, Thrips palmi Karny; melon weevil, Baris traegardhi Auriv; or melon worm, Diaphania hyalinata (Linnaeus), a widespread pest of pumpkins, melons and other members of the gourd family.[4]Gordon Gordh, comp. A Dictionary of Entomology (New York: CABI Publishing, 2001), 566.

Long Camp’s Short Treatise

As to familiar versus new insects, Lewis reserved that overall but incomplete record for his month-long period of relative repose among the Nez Perce people in May of 1806. Nicholas Biddle paraphrased Lewis’s single paragraph that sufficed as a response to the President’s directive. For nearly a full century it represented all Lewis had to say about the subject:

Most of the insects common to the United States are seen in this country: such as the butterfly, the common house-fly, the blowing-fly, the horse-fly, except one species of it, the gold-colored ear-fly, the place of which is supplied by a fly of a brown color, which attaches itself to the same part of the horse and is equally troublesome. There are likewise nearly all the varieties of beetles known in the Atlantic States, except the large cow-beetle, and the black beetle commonly called the tumble-bug. Neither the hornet, the wasp, nor the yellowjacket inhabits this part of the country; but there is an insect resembling the last of these, though much larger, which is very numerous, particularly in the Rocky Mountains and on the waters of the Columbia; the body and abdomen are yellow, with transverse circles of black; the head is black, and the wings, which are four in number, are of a dark brown color. Their nests are built in the ground and resemble that of the hornet, with an outer covering to the comb. These insects are fierce and sting very severely, so that we found them very troublesome in frightening our horses as we passed the mountains. The silkworm is also found here, as well as the bumblebee, though the honey-bee is not.[5]History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark from St. Louis, to the Sources of the Missouri; Thence Across the Rocky Mountains and Down the River Columbia to the Pacific … Continue reading

Lewis’s brief enumeration of insect species was not only incomplete, but also superficial, and on both counts it clearly reflected the status of entomology in the United States at the opening of the 19th century. As we have shown in our summaries of his treatments of mosquitoes, eye gnat, and Fleas, contemporary entomology generally treated most insects as pests to be swatted or squashed, and almost unanimously cursed or shunned them. Naturally, since the horse was the principal source of power for agricultural purposes as well as the basic means of transportation and communication, Lewis noticed certain insects, chiefly those that annoyed him in that context, but made few efforts–such as his physical description of the yellowjacket in the summary quoted above–to contribute toward further understanding of any of them. His plantation, Locust (the tree, not the insect) Hill near Charlottesville, Virginia, was large–more than 2,000 acres–but had he been a farmer at heart, he might, for instance, have inquired of the Mandan and Arikara women about their ways of dealing with agricultural pests. It may be that his negative attitudes toward them as native peoples momentarily overshadowed any impulse he might have had towards learning much from them personally.

Notes

| ↑1 | Aristotle, On the Parts of Animals, in James Lennox, “Aristotle’s Biology,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta, ed. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Donald D. Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents 1783–1854 (Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1978), 63. |

| ↑3 | Lorus and Margery Milne, National Audubon Society Guide to North American Insects & Spiders (New York: Knopf, 1980), 603. |

| ↑4 | Gordon Gordh, comp. A Dictionary of Entomology (New York: CABI Publishing, 2001), 566. |

| ↑5 | History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark from St. Louis, to the Sources of the Missouri; Thence Across the Rocky Mountains and Down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean; Performed during the years 1804-5-6; by Order of the Government of the United States. Prepared for the press by Paul Allen. 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1814), 2:295. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.