The captains’ careful observations of the geography, natural history, and ethnography of the American west and Pacific Northwest left an influence on science that remains today.

Related Pages

We may never know the full historical impact of Lewis and Clark’s discoveries upon nineteenth-century scientific inquiry, but this example highlights how just a series of conversations with the returning explorers allowed a significant earth science discovery to be revealed to the scientific community.

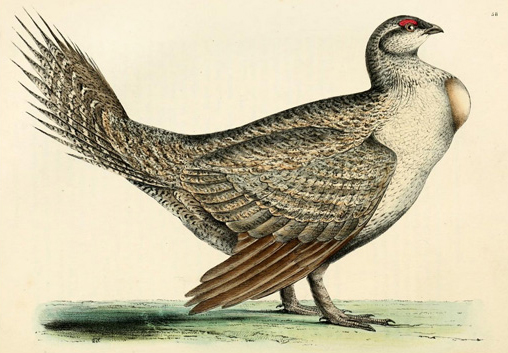

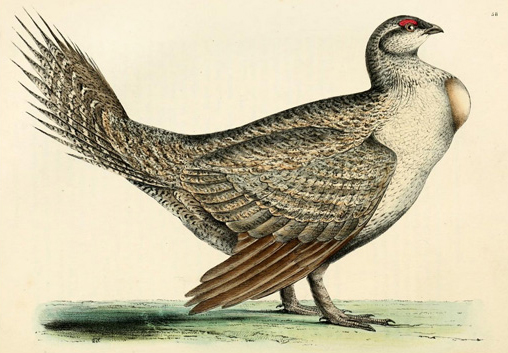

David Douglas returned to England with many hundreds of flora and fauna specimens to process. During his stay he wrote or contributed to more than a dozen scientific papers, several of which build on the seminal first collections of Lewis and Clark.

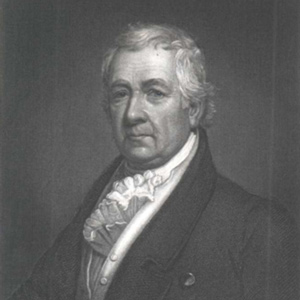

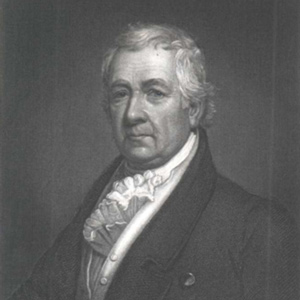

Perhaps the naturalist most influenced by Lewis and Clark was Alexander Wilson. Considered by many as the “Father of American Ornithology” he actively used their writings and specimens to complete his own works.

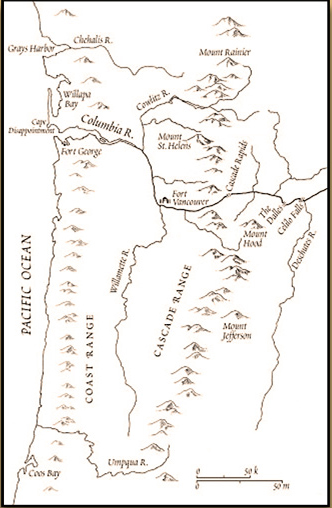

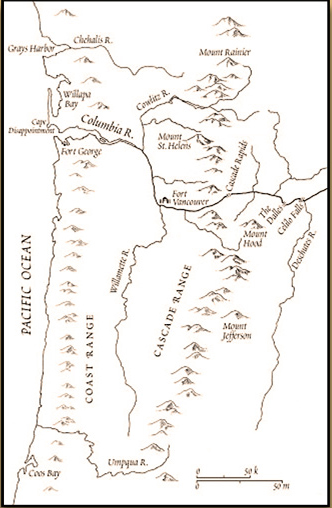

Douglas recognized landmarks from Vancouver’s and William Clark’s maps as soon as he sighted Cape Disappointment at the Columbia River’s fearsome bar. The collector continued to name familiar sentinels as he moved inland including “Mount Jefferson of Lewis and Clarke.”

The Fort Mandan shipment of specimens was registered in the so-called “Donation Book” that was compiled for the Lewis and Clark materials received in November 1805. The entries were sequentially numbered by John Vaughan of the APS in Philadelphia.

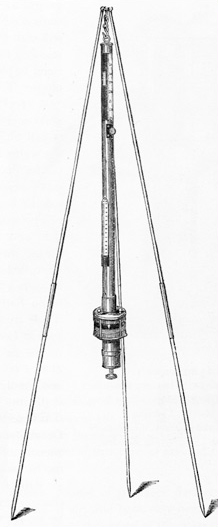

As Douglas and surveyor George Barnston set up their instruments, the pair would have been well aware that they were repeating observations taken by the Corps of Discovery in 1805 and by David Thompson in 1811.

The son of a farmer and merchant in Philadelphia, Richard Harlan became a leading American figure in anatomical studies. He would become the man who named the only fossil that now survives from the Lewis and Clark expedition.

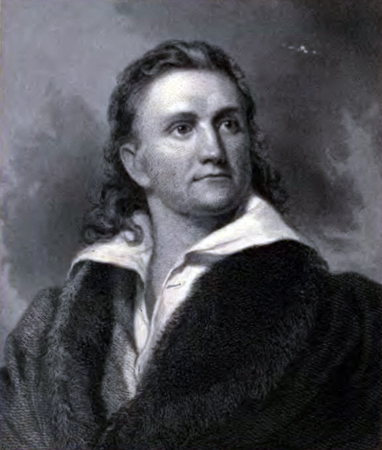

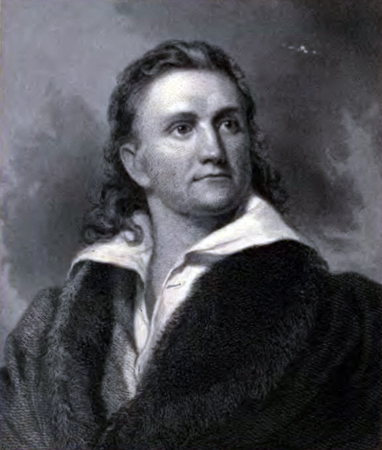

America’s greatest ornithologist, John James Audubon, was just starting his career when Lewis and Clark returned, and there is ample evidence that he drew inspiration from Lewis and Clark’s writings.

For nearly 100 years, the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s full contribution to natural science was underpublished and a disappointment to many scientists expecting to learn more about the natural history of the regions explored. When it came to the mosquito, these naturalists were doubly disappointed.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.