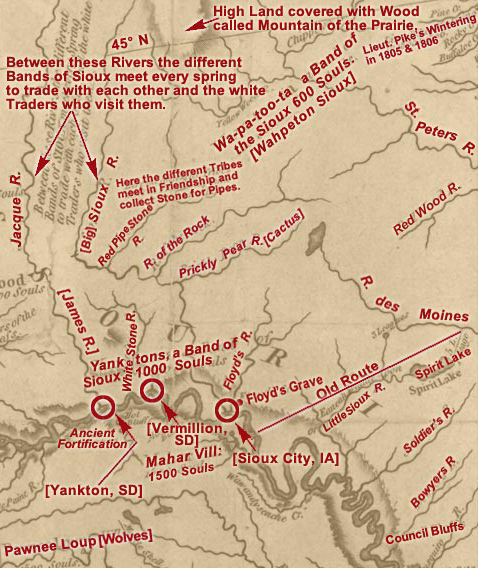

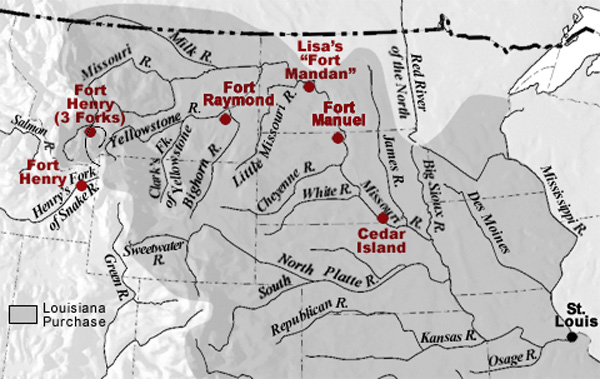

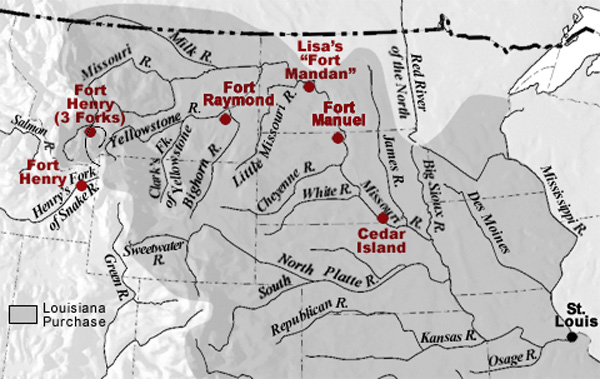

Many of Clark’s maps are analyzed and illustrated with interactive figures comparing his drawing with present-day geographic labels.

On most traveling days, Clark recorded the expedition’s route, tributaries, landmarks, and Native American villages on sketch maps. He also listed distances and course direction changes in his field notes. Added to this, he interviewed numerous fur traders and Native Americans to gain geographical information about places not traveled. During pauses, especially during the winters at Forts Mandan and Clatsop, he drafted elaborate and surprisingly accurate maps of the American Northwest. He continued working on his maps after returning to St. Louis, often amending and adding information gained from subsequent travelers.

The shuttling of all the baggage and six canoes across the prairie to the upper portage camp opposite White Bear Islands began on 21 June 1805 and was completed on 2 July 1805. All in all, it was one of the most grueling undertakings on the entire expedition.

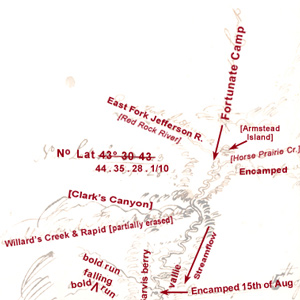

Lewis: “here I halted and examined those streams and readily discovered from their size that it would be vain to attempt the navigation of either any further.”

Before arriving at the three forks of the Missouri, Whitehouse wrote that they “passed some rough rockey hills, which we expect from the account we have from the Indian Woman that is with us, to be the commencement of the Second chain of the Rockey Mountains.

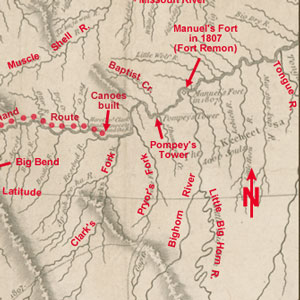

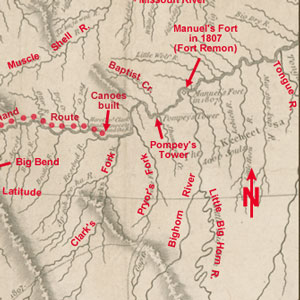

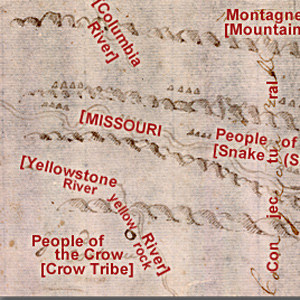

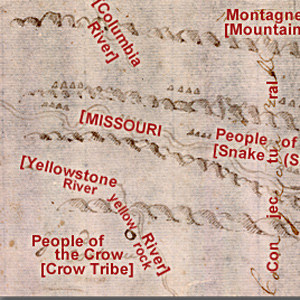

Mapping the Yellowstone

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark’s map of 1814 shows his post-expeditionary conclusions regarding the lay of the land from just west of the Three Forks of the Missouri River, roughly 230 air miles eastward along the Yellowstone to the Tongue River.

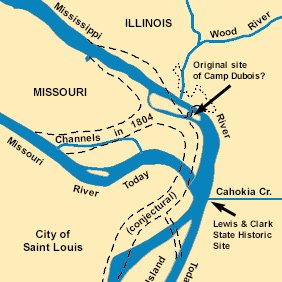

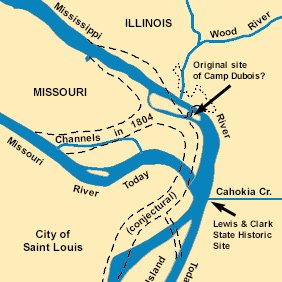

The Mouth of the Missouri

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The Missouri River still contributes its tint a few miles north of St. Louis. It is difficult to determine exactly how much, and how often, the confluence of the Missouri and the Mississippi Rivers changed during the nine decades after the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

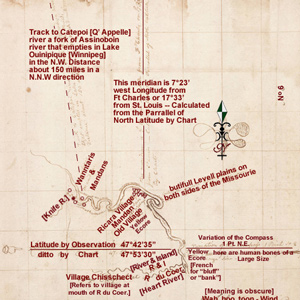

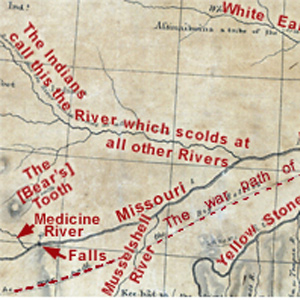

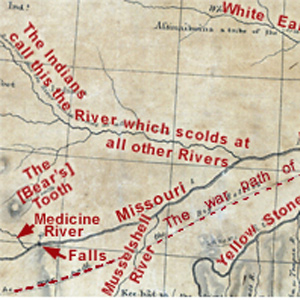

Clark’s Fort Mandan Maps

by Joseph A. Mussulman

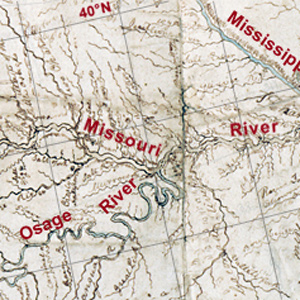

While wintering over at Fort Mandan, Clark made a series of maps based on Indian information and previous traders such as John Evans and François Larocque.

On 1 June 1804, the expedition arrived at the mouth of the Osage River, one of the major Indian trail intersections on the lower Missouri. From the height on the point, Clark wrote: “I had a delightfull prospect of the Missouries up & down, also the Osage R. up.”

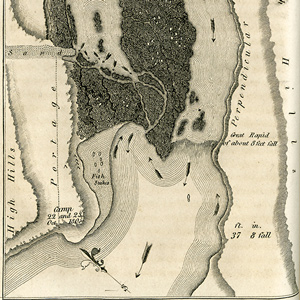

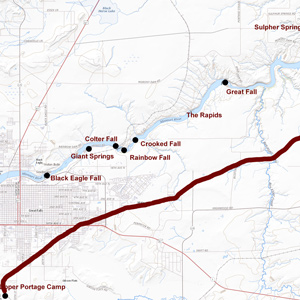

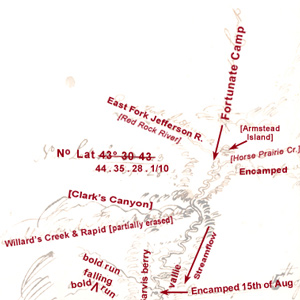

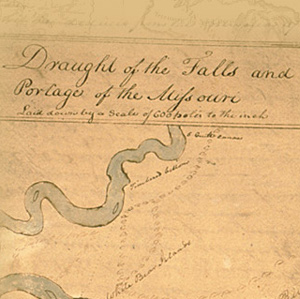

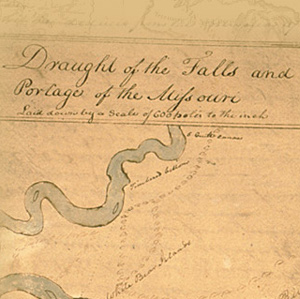

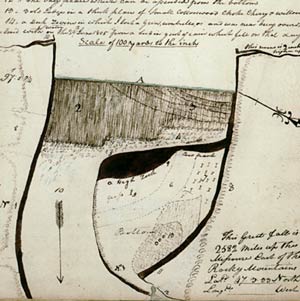

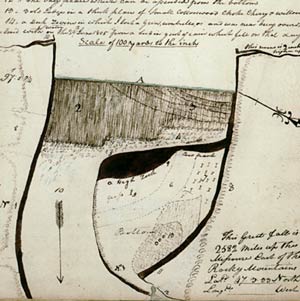

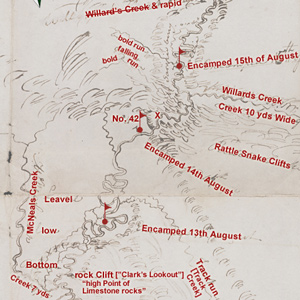

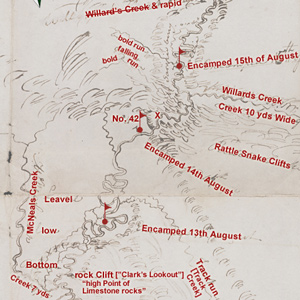

Mapping the Falls

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The falls of the Missouri comprised the most remarkable of all the “remarkeable points” that Clark described and mapped in conscientious obedience to an order from Thomas Jefferson to take observations “with great pains & accuracy.”

Clark produced this map of Lewis’s route sometime after the Corps was reunited on 12 August 1806, near today’s New Town, North Dakota.

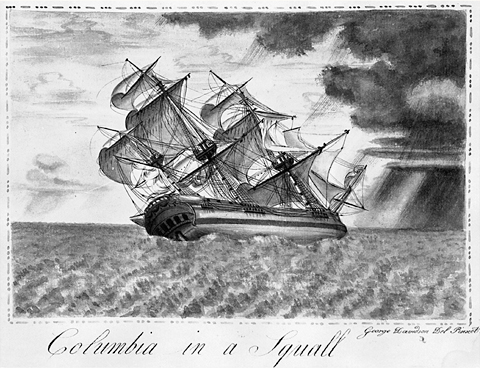

The Corps of Discovery was but one of a great number of expeditions by land and sea made between 1770 and 1870 across the North American continent in search of a Northwest Passage. Lewis knew much about the mouth of the Columbia River.

Celestial observations at the Kansas and Missouri river confluence began shortly after 8 a.m. on 27 June 1804. The first observation would provide the data necessary to calculate the magnetic declination.

The visit to this prairie hill was among the more bizarre sidelights of the whole expedition, but evidently it was not entirely unexpected. Seventy-six years earlier, explorer Pierre La Véndrye called the place the “Dwelling of the Spirits.”

The historic Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track Across the Western Portion of North America can fruitfully serve as a major palimpsest of American history as of the year in which it was created, 1810.

After passing the salt works and continuing along the “round Slippery Stones under a high hill,” Clark related, “my guide made a Sudin halt, pointed to the top of the mountain and uttered the word Pe Shack which means bad, and made Signs that we . . . must pass over that mountain.

Lewis and his canoes slowly approached the forks, “the current still so rapid that the men are in a continual state of their utmost exertion to get on, and they begin to weaken fast from this continual state of violent exertion.” He described the “extensive and beatifull plains and meadows.”

Continuing north up the North Fork Salmon River, they leave a good Indian road and must cut their own trail. Were they lost? Sergeant Gass’s laconic remark gives us a hint: “This was not the creek our guide wished to have come upon.”

Clark evidently began compiling a map of the Northern Rockies after meeting with Hugh Heney at Fort Mandan on 18 December 1804, and continued adding information acquired from other traders, as well as from Indians. The reality, he would find, was much different.

Mapping Unknown Lands

by John Logan Allen

Geography professor John Logan Allen explains the tasks and methods used to map the lands traveled by the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

On 17 June 1805, Clark and five men set out to determine the best portage route around the Great Falls of the Missouri. On the way up the river, he stopped to also measure the fall of the river and to map the falls.

Manuel Lisa’s men at Fort Raymond not only encouraged the Crows to come trade with them, but they set out parties to trap beaver on their own. It was the latter effort that led to hostilities with the Blackfeet that affected Potts, Drouillard, and Colter.

It was a clear night. The moon, just two days short of its first quarter, was 23° above the horizon bearing S78° W when the captains began their observations about 9:30 p.m.

On the 23 August 1805, the centuries-old fantasy of a “water route across the continent for the purposes of commerce” dissolved in the roar of an unimaginable torrent–one of the most dangerous, unforgiving rivers in North America, that would later be called “The River of No Return.”

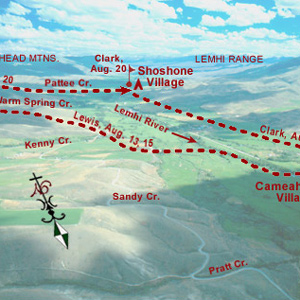

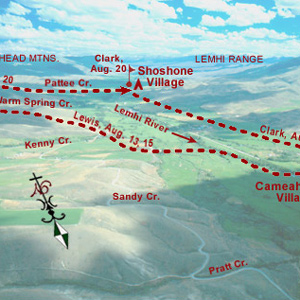

Meeting the Shoshones

by Joseph A. Mussulman

A few more Shoshones came in sight. Making all the benevolent signs and sounds he could think of, pondering ways to bring the wary Indians within talking distance, Lewis finally touched the hand of an elderly woman, and the spark of international friendship was struck.

Lewis’s simple, orderly concept of the Rocky Mountains began to crumble. The truth was, this was not the easy portage to the Pacific Ocean they had expected from the beginning. Countless “chains” of mountains still intervened.

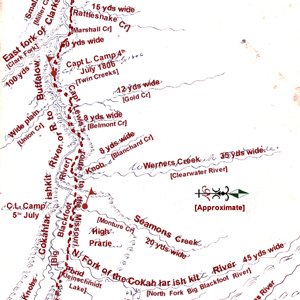

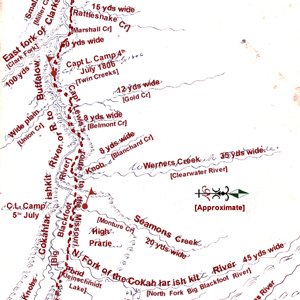

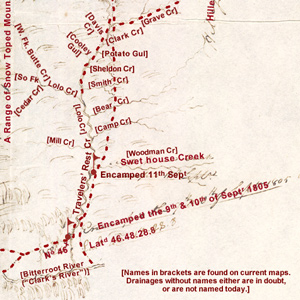

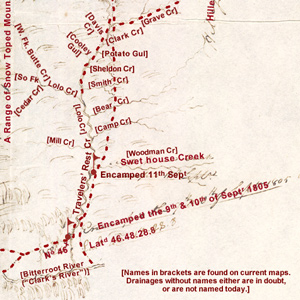

Mapping the Lolo Trail

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark did not randomly insert wiggly lines merely to hint at the topography around K’useyneiskit. By comparing his sketches with a modern USGS map we can make reasonably good guesses as to what drainages he actually saw.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.