William Dunbar was Jefferson’s Enlightenment ally in Natchez, and Dr. George Hunter was one of the finest chemists in early American history. While Lewis and Clark wintered in North Dakota, Dunbar and Hunter explored the Ouachita River in Arkansas. They would alter Jefferson’s plans to explore the Red and Arkansas Rivers.—Ed.[1]This article is a small excerpt from We Proceeded On, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. Jay H. Buckley, “Exploring the Louisiana Purchase and Its … Continue reading

Hunter and Dunbar

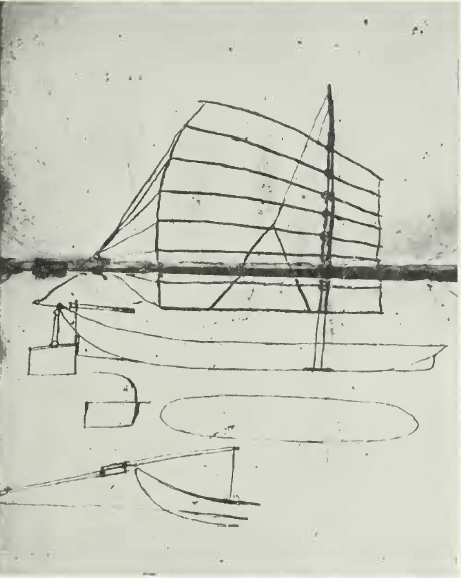

Hunter and Dunbar’s Boat

Sketch by George Hunter

From John F. McDermott, ed., “The Western Journals of George Hunter, 1796-1805,” special issue, Proceedings, American Philosophical Society 103, no. 5 (1959). Reprint, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1963.

Hunter started in much the same way as Meriwether Lewis. He went to Pittsburgh by horse shipping the cargo separately from Philadelphia by wagon. In Pittsburgh, he had to wait for a boat to be made. Of his two-week delay, he wrote:

Whilst at Pittsburgh I was employed in superintending the building of a boat to carry us to Natchez . . . . This Boat is fifty feet long on deck, 30 feet straight Keell, flat bottom somewhat resenbling a long Scow in use to ferry over waggons &c. . . . & furnished with a Stout Mast 36 geet long a Sail 24 feet by 27, in the Chinese stile . . . .

Hunter mentions that the sail cloth was furnished by Lieutenant Moses Hooke, the military agent at Fort Fayette. Of Hooke, he informed Henry Dearborn, Secretary of War:

Leiut Hook afforded me every assistance in his power. I also recd. of him a Camp ax for the use of the Boat & a musket which may be useful in the river[;] this I am to return at Natchez.—He appears to be a very exact & diligent officer.

Moses Hooke helped Meriwether Lewis in the building of the Lewis and Clark expedition’s military barge that went as far as the Fort Mandan at the Knife River Indian Villages in present-day North Dakota. On 26 July 1803, Lewis asked Thomas Jefferson to authorize Lieutenant Hooke to co-lead the expedition should William Clark decline to join.—Ed.

With Lewis and Clark ascending the Missouri and exploring the northern and western boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase, President Thomas Jefferson selected Scottish-born scientist Sir William Dunbar and Philadelphia chemist George Hunter to explore the Purchase’s southern boundary in present-day Louisiana and Texas. The proposed Grand Expedition or Excursion into the Southwest was an ambitious undertaking on a scale similar to Lewis and Clark’s trip up the Missouri. The president tasked Dunbar and Hunter with exploring the headwaters and courses of the Red and Arkansas rivers by ascending the Red, portaging across the mountains, and descending the Arkansas.

Dunbar, owner of The Forest plantation nine miles south of Natchez, was an experienced surveyor who had traded with Indians and had surveyed the Spanish-U.S. border and lower Mississippi Valley in 1798. After becoming a U.S. citizen, he received the honor of being named surveyor general of Mississippi and made meteorological observations of the region. An acquaintance of Jefferson through the American Philosophical Society, Dunbar constructed an observatory at his plantation equipped with the best astronomical instruments available. He also conducted extensive scientific research on chemically treating soils, increasing crop yields, and developing and improving agricultural machinery such as the cotton baler. He was also skilled in mathematics, botany, zoology, ethnology, meteorology, and other sciences.[2]Arthur H. DeRosier, Jr., William Dunbar: Scientific Pioneer of the Old Southwest (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007).

George Hunter, like Dunbar born in Scotland, was one of the finest chemists in early American history. He journeyed west in 1796 and 1802 to explore the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. His trips provided opportunities for him to visit mining operations, salt licks, and other interesting phenomena before he returned to Philadelphia, where he worked as a druggist and doctor. After the purchase, Hunter expressed an interest, and Jefferson appointed him co-leader of the Red River expedition. Subsequently, his widely circulated accounts of the southern portions of the Louisiana Purchase gained general acceptance.[3]Hunter kept four extensive journals of his western trips and observations of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. John F. McDermott, ed., The Western Journals of Dr. George Hunter, 1796–1805 … Continue reading

Up the Ouachita

Hunter arrived at Dunbar’s plantation in late July 1804. Jefferson initially wanted to dispatch the expedition earlier, but Spain’s unwillingness to issue passports and Osage Chief Great Track’s threat to kill Americans who invaded Osage land forced them to reconsider their plans. Jefferson, who had requested and received a $3,000 appropriation for the venture, thought it best to exercise caution. To avoid possible trouble with the Osages and Spaniards, Dunbar suggested they pursue an alternative reconnaissance up the Ouachita River, one of the major tributaries along the lower Red, pointing out there were many “curiosities” along that route. Jefferson consented to the change.[4]For correspondence between Dunbar and Jefferson, see Eron Rowland, comp., Life, Letters, and Papers of William Dunbar (Jackson: Press of the Mississippi Historical Society, 1930). Dunbar’s … Continue reading

On 16 October 1804, Hunter and his teenage son, along with Dunbar, his two slaves and a servant, and thirteen soldiers, set out from St. Catherine’s Landing on the Mississippi River. During the autumn and winter of 1804, they ascended the Ouachita. Hunter’s and Dunbar’s journals contain excellent descriptions of flora, fauna, and soils, as well as accurate thermometer readings and astronomical tabulations. Dunbar utilized a pocket chronometer, a circle of reflection, a compass, and an artificial horizon to take latitudinal and longitudinal readings to make as accurate a map as possible.

Difficulties

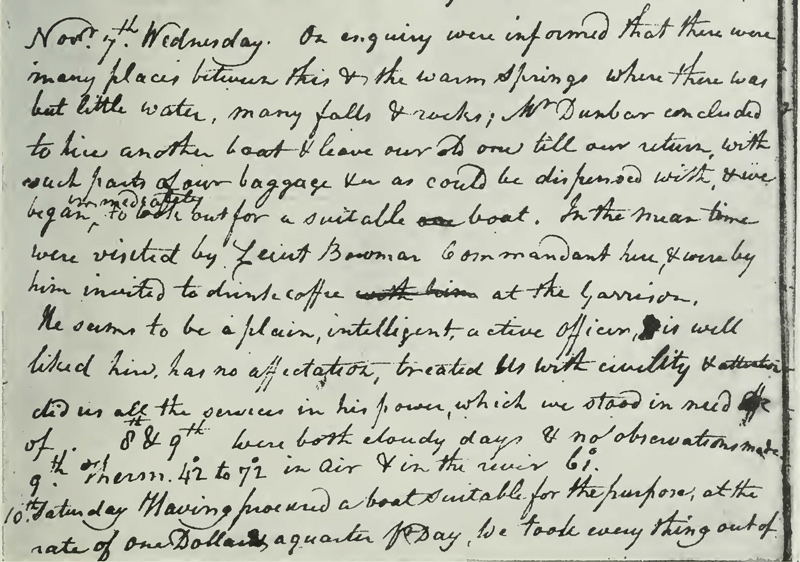

Transcription:

Novr. 7th. Wednesday. On enquiry were informed that there were in many places between this & the warm springs where there was but little water, many falls & rocks; Mr. Dunbar concluded to hire another boat & leave our old one till our return, with such parts of our baggage &cc as could be dispensed with, & we began immediately to look out for a suitable boat. In the meantime were visited by Leiut Bowmar Commandant here. & were by him invited to drink coffee at the Garrison. He seems to be a plain, intelligent, active officer is well liked here, has no affectation, treated us with civility & attention[,] did us all the services in his power, which we stood in need of 8th & 9th were both cloudy days & no observations made. 9th Therm. 42° to 72° in Air & in the river 61°.

10th. Saturday Having procured a boat suitable for the purpose, at the rate of one Dollar & a quarter pr. Day, we took every thing out of the old one . . . .

Unfortunately, the boat that Hunter had designed and brought down from Pittsburgh did not work as well in inland waterways because its draft was too deep. At Fort Miro (renamed Ouachita Post, now Monroe, Louisiana), Dunbar employed guide Samuel Blazier and, to proceed onward, secured a flatboat with a cabin on deck. On 22 November 1804, while cleaning his gun, Hunter accidentally shot himself, wounding his hand and his head, and burning his eyes. Despite the mishap, they proceeded on their journey, strenuously working up the rapids, or “chutes,” caused by the Ozark Mountains, before arriving in the hot springs area of present-day Arkansas. They spent nearly a month studying the 150-degree water, geological features, and plant and animal life of the area before continuing their journey. By 8 January 1805, cold temperatures and shallow water had turned them back, and while floating downstream they encountered an entourage of Quapaw Indians, who provided them with valuable geographical information. After stopping briefly at Fort Miro, they arrived in Natchez on 27 January 1805.[5]Trey Berry, Pam Beasley, and Jeanne Clements, eds., The Forgotten Expedition: The Louisiana Purchase Journals of Dunbar and Hunter, 1804–1805 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006); … Continue reading

Follow-up

Both men presumed that their follow-up excursion up the Red would occur in 1805, but personal circumstances, advancing age (both men were in their fifties), new congressional and War Department directives, and the difficulties of their winter journey up the Ouachita persuaded them not to volunteer for the potentially more hazardous Grand Excursion up the Red River. Continued Osage resistance to American interlopers along the Arkansas and the expected difficulties of a mountain portage further compromised Jefferson’s proposal for a team to ascend the Red and cross over and descend the Arkansas. The duo recommended instead that the next expedition should focus solely on the Red, and Jefferson concurred in May 1805.[6]For the Red River exploration, see Freeman-Custis Expedition. With the new plan in place, Jefferson continued corresponding with Dunbar who, along with Hunter, began recruiting replacements to lead a party up the Red.[7]John F. McDermott, ed., “The Western Journals of George Hunter, 1796-1805,” special issue, Proceedings, American Philosophical Society 103, no. 5 (1959). Reprint, Philadelphia: American … Continue reading

Though the Hunter and Dunbar journey was relatively short, their journals and maps provided detailed scientific observations and data on the region’s plant and animal life and its resources. They described an active trade between trappers and Indians along the Red, Black, and Ouachita rivers and chronicled the locations of hot springs, which later attracted hosts of individuals seeking relief from their ailments by soaking in the hot mineral water. Their findings brought them recognition and acclaim after their return. Dunbar resumed oversight of his plantation and continued his scientific observation and writing, providing one of the first topographical and scientific descriptions of the Mississippi Valley. He likewise published a dozen papers on Indian sign language, natural history, and astronomy in the American Philosophical Society’s journal before his death in 1810. Hunter moved his family to Louisiana in 1815 and operated a steam distillery. He was known as a Jeffersonian explorer until his death in New Orleans in 1823.

Related Pages

March 3, 1803

Jefferson's Mississippi strategy

In Washington City, President Jefferson writes to William Dunbar— a naturalist, surveyor, and scientist living in the Mississippi Territory. He explains his plan for obtaining New Orleans and the Floridas.

October 16, 1804

"Goat" hunting

The expedition struggles 14 river miles between present Fort Yates and Beaver Creek in North Dakota. Some Arikaras hunt pronghorn, and Lewis adds common poorwill and creeping juniper to his collection.

November 22, 1804

Domestic violence

A Mandan man threatens to kill his wife for having slept with Sgt. Ordway. Clark orders the sergeant to give the man some trade goods. Twelve bushels of corn—still on the cob—is brought in.

January 8, 1805

Sgt. Ordway's visit

Braving a cold northwest wind, Sgt. Ordway visits a Mandan village, likely the one nearest Fort Mandan—Mitutanka. On the Ouachita River in present Arkansas, the Hunter and Dunbar Expedition turns back.

February 2, 1805

Mr. Larocque's compass

At Fort Mandan, Lewis fixes North West Company trader François-Antoine Larocque’s compass, but latter’s attempt to join the expedition fails. One of the interpreters’ wives—perhaps Sacagawea—is taken ill.

March 12, 1805

Charbonneau quits

At Fort Mandan, Hidatsa interpreter Toussaint Charbonneau quits, and in Washington City, Spanish Minister Yrujo complains that Jefferson’s western expeditions are intruding on Spanish territory.

March 14, 1805

Charbonneau moves out

Interpreter Toussaint Charbonneau terminates his employment and moves out of Fort Mandan with the intent to return to his Hidatsa village. The enlisted men are tasked with shelling corn.

May 25, 1805

Into the breaks

The geological formations change as they enter the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument. George Drouillard kills the expedition’s first bighorn sheep, and Lewis describes the animal.

January 12, 1806

Conserving elk

At Fort Clatsop near the Pacific Ocean, George Drouillard kills seven elk and new plan to conserve meat begins. In Washington City, President Jefferson shares news of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Notes

| ↑1 | This article is a small excerpt from We Proceeded On, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. Jay H. Buckley, “Exploring the Louisiana Purchase and Its Borderlands: The Lewis and Clark, Hunter and Dunbar, Zebulon Pike, and Freeman and Custis Expeditions in Perspective,” in two parts, We Proceeded On, Vol. 46 no. 3, August 2020 and vol. 47 no. 1, February 2021. The full-length articles are available at our sister website: lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol46no3.pdf#page=13 and lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol47no1.pdf#page=14. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Arthur H. DeRosier, Jr., William Dunbar: Scientific Pioneer of the Old Southwest (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007). |

| ↑3 | Hunter kept four extensive journals of his western trips and observations of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. John F. McDermott, ed., The Western Journals of Dr. George Hunter, 1796–1805 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1963). |

| ↑4 | For correspondence between Dunbar and Jefferson, see Eron Rowland, comp., Life, Letters, and Papers of William Dunbar (Jackson: Press of the Mississippi Historical Society, 1930). Dunbar’s journal for the trip up the Ouachita and other correspondence and material are in the William Dunbar Collection, Riley-Hickingbotham Library, Ouachita Baptist University, Arkadelphia, Arkansas. The “boiling springs” are present-day Hot Springs National Park. Jefferson had reason to be cautious with exploring Spanish-contested areas. Philip Nolan, a Wilkinson protégé, had tried operating a contraband and horse-trading network among the Comanches and Taovayas in Spanish Texas. Operating out of Natchez, he explored the Red River country before being captured and killed for spying in central Texas in 1801. |

| ↑5 | Trey Berry, Pam Beasley, and Jeanne Clements, eds., The Forgotten Expedition: The Louisiana Purchase Journals of Dunbar and Hunter, 1804–1805 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006); Trey Berry, “The Expedition of William Dunbar and George Hunter along the Ouachita River, 1804–1805,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 62, no. 4 (2003): 386-403. |

| ↑6 | For the Red River exploration, see Freeman-Custis Expedition. |

| ↑7 | John F. McDermott, ed., “The Western Journals of George Hunter, 1796-1805,” special issue, Proceedings, American Philosophical Society 103, no. 5 (1959). Reprint, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1963. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.