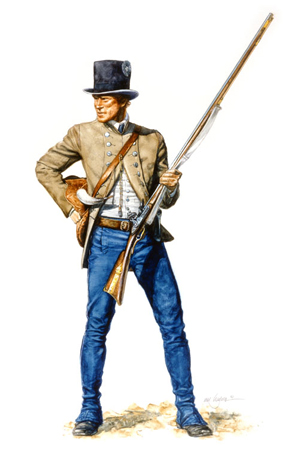

What we know of military protocol and the characters of Lewis and Clark makes it clear that the Corps of Discovery was a military expedition where discipline, uniformity, and personal appearance mattered.

Perhaps no other episode in American history better represents the courage, determination, and dedication of the American soldier than the epic journey of the Corps of Discovery. The United States Army made a singular contribution to the success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The Army furnished the organization and much of the manpower, equipment and supplies. The skill, teamwork, and courage of each soldier contributed significantly to overcoming the huge natural obstacles to crossing the continent. And, the generosity and support of Native American tribes, whose political sovereignty and autonomy were potent realities, guaranteed the success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

—Charles E. White[1]“Lewis and Clark: Misperception and Reality,” Corps of Discovery: United States Army, https://history.army.mil/lc/The%20Mission/Dispelling_Myth.htm accessed 21 April 2022.

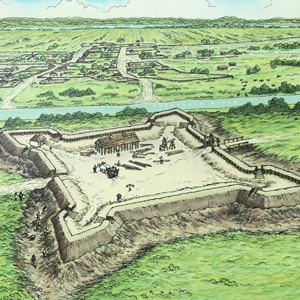

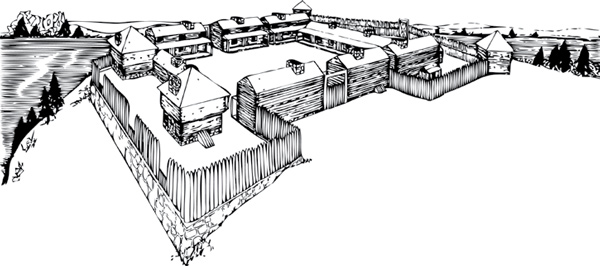

Fort Kaskaskia

Preliminary outpost

Archaeological investigations by the author and his students reveal the location of the American Fort Kaskaskia. Extracts from “Bound to the Western Waters: Searching for Lewis and Clark at Fort Kaskaskia, Illinois” by the lead archaeologist.

Army Life and Leadership

by Sherman L. Fleek

Retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel and former chief historian of the National Guard Bureau discusses frontier army life in 1803 and the exemplary military leadership of the co-captains and non-commissioned officers.

Expedition Members

As Secretary of War during the expedition, Henry Dearborn made several decisions critical to the it’s success, and he was the one who gave Clark’s the military rank of lieutenant.

Army Life in 1803

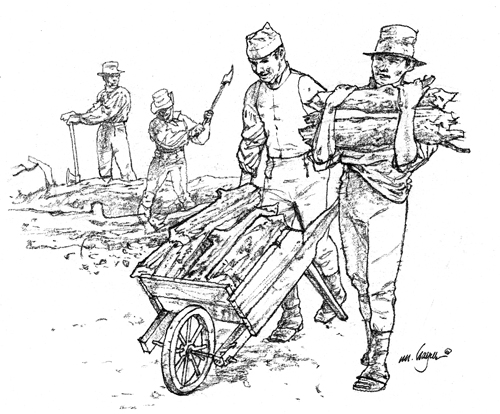

Life in the U.S. Army in 1803, especially on the western frontier, provided little free-time, but the day’s alcohol ration gave some relief from the day’s fatigue duties.

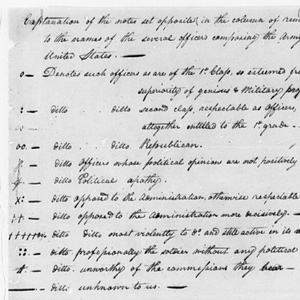

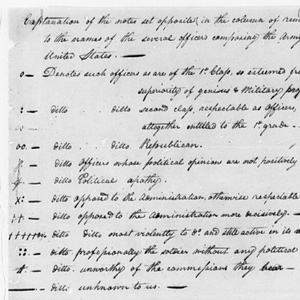

In his capacity as the President’s secretary, Meriwether Lewis prepared a report in which he classified the Army’s officers by military merit and by political affiliation, if known. Both of these factors were considered in identifying candidates for dismissal.

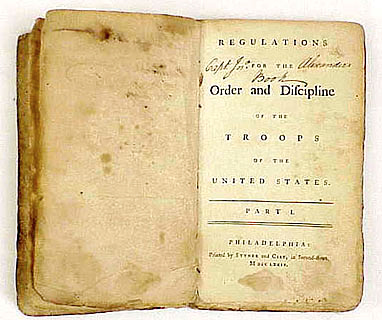

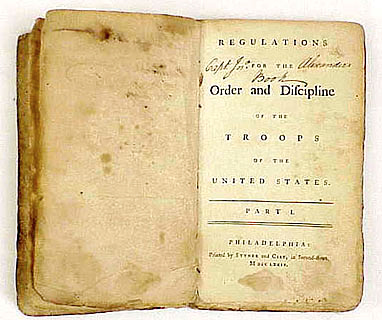

Steuben’s book was much more than a “blue book” of military regulations and procedures. It concluded with guides to character, pride and conduct for men of every rank, from regimental commanders and their subordinates, to non-commissioned officers and privates.

Prior to the Lewis and Clark Expedition, William Clark and Meriwether Lewis began their military careers by actively serving in their local militias. After that, they joined the regular army and first met during the Ohio Valley’s Indian wars.

The first court martial took place on 29 March 1804, when John Colter, Robert Frazer, and John Shields were called before the court. Discreetly, Clark committed no details of this one to his journal, and no record of it was entered in the Orderly Book.

A multitude duties awaited the hapless private, and idle hands and feet were never knowingly allowed in a military camp. Most fatigue duties rewarded the men with an extra gill (1/4 of a pint) of whiskey each day.

The members of the expedition began their journey as a wild bunch of hard drinking, brawling, and insubordinate rowdies. By 7 April 1805, the day the Corps of Northwestern Discovery pulled out of Fort Mandan, Lewis described his men as enjoying “a most perfect harmony.”

Lewis had assured Clark that their situations would be identical in every respect, beginning with rank. The fact that Clark was actually a lieutenant was a secret kept throughout the expedition.

Army Hygiene

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Officers were to see that their men’s hands and faces were daily “washed clean” and their hair combed. Soap was relatively expensive, and if individuals or families couldn’t manage to make their own, they just went without.

No military commander of the 18th-century would have thought of leading his troops on any mission without planning for liquor. In legislation and military orders of the day, the ration was typically expressed in “gills.”

The Permanent Party

by Arlen J. Large

Between St. Louis and the Pacific Ocean, and on the return to St. Louis, personnel decisions needed to me be made.

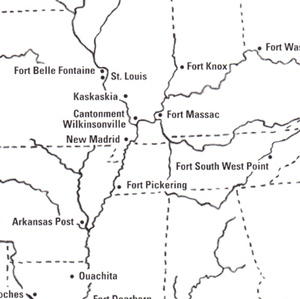

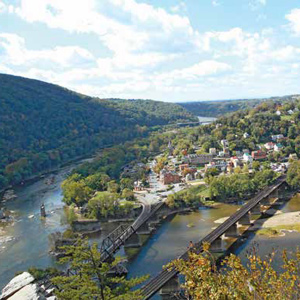

Fort Southwest Point, a frontier garrison in eastern Tennessee during the late 1790s and early 1800s, played an important role in the planning for and recruitment of soldiers for the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

It is a remarkable fact that Lewis’s planning for the expedition resulted in a surplus of four essential commodities: lead for bullets and powder to fire them, ink to write with and paper to write on. It was equally significant, as far as most of the men were concerned, that they ran short of tobacco and whiskey.

Six years before signing on with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, George Drouillard took part in a sensitive international mission for the United States Army. This mission was probably just one of Drouillard’s many services to the United States in the last decade of the eighteenth century.

During preparations, Lewis relied on the Harpers Ferry Armory and Arsenal for the guns and hardware that would meet his unique requirements.

Weaponry

Tools of survival

The guns and various military accouterments carried by the expedition members needed to do more than deter attacks and provide food, they needed to impress the Native Americans with whom American weapons could be a primary item of trade.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Lewis and Clark: Misperception and Reality,” Corps of Discovery: United States Army, https://history.army.mil/lc/The%20Mission/Dispelling_Myth.htm accessed 21 April 2022. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.