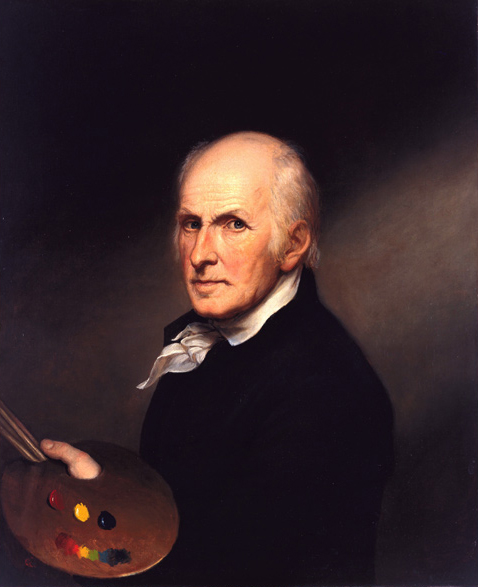

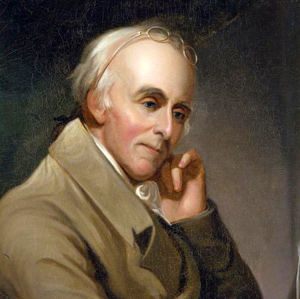

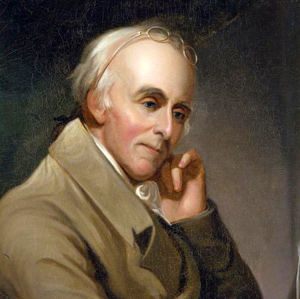

Self-Portrait with Spectacles

by Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827)

Oil on canvas, mounted on wood, 26 3/16 x 22 5/16 in. (66.5 x 56.7 cm.). Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Henry D. Gilpin Fund, #1939.18.

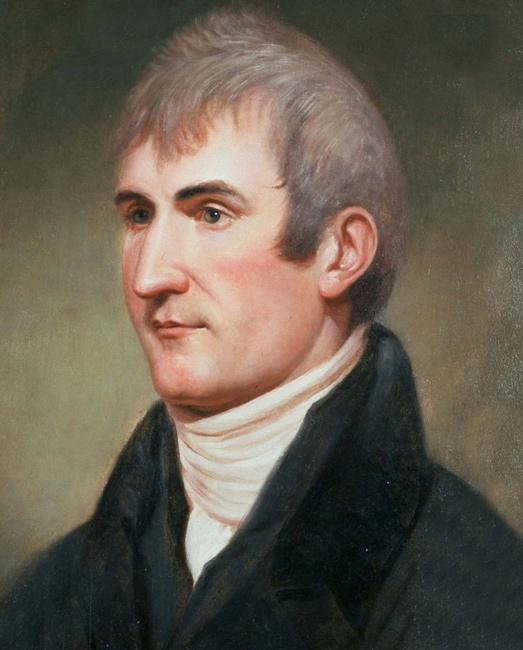

This series of articles by Charles Greifenstein looks at the life and contributions of artist and museum keeper Charles Willson Peale. At his Philadelphia museum, he displayed many of the expedition’s specimens helping to preserve the Lewis and Clark legacy. His portraits of several people key to the expedition’s success—including Meriwether Lewis and William Clark—are used here to tell the story of the “Corps of Northwestern Discovery.”

Pages about Charles Willson Peale

Preserving the Expedition

Peale's specimen displays

by Charles Greifenstein

The stuffed birds and mammals, the skins and skeletons, and especially the Indian artifacts, that Peale received—mainly from Lewis, through Jefferson—greatly benefited the museum and consequently the public’s appreciation of the expedition.

Peale’s Museum

by Charles Greifenstein

Peale’s Museum showcased the natural treasures of the new country such as mastodon fossils from Big Bone Lick and the first public display of artifacts from the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Peale’s Early Years

by Charles Greifenstein

As the oldest child, Charles Willson very early faced the problem of earning a living for himself and helping support his mother and siblings. By 1761 Peale was able to set himself up as an independent saddler and then learned watch repair, harness making, upholstering, and silversmithing.

Peale the Patriot

by Charles Greifenstein

Captain Peale’s militia company sailed up the Delaware River toward Trenton, arriving in time to see Washington’s bedraggled army cross into Pennsylvania. As the war progressed, he found himself strongly drawn to the democratizing aspects of the revolution.

Peale the Painter

by Charles Greifenstein

Portrait painting pointed to better prospects than saddle-making. Leaving Rachel and their young son, with high hopes for his new profession and eager to see that the inheritance promised his father was secure, Peale sailed for England in December 1766.

Peale’s Later Years

by Charles Greifenstein

Purchasing over one hundred acres of rolling land in 1810, Peale expected that as a gentleman farmer he would give himself over to a life of art. He did paint more, but Peale, as energetic as ever, also poured himself into the agricultural arts and technological invention.

Pages with Artwork by Peale

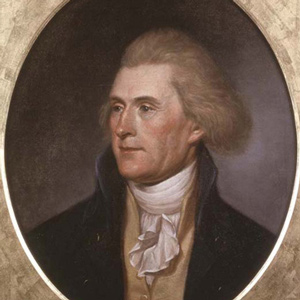

To understand the Lewis and Clark Expedition, one must understand this complex American leader.

James Wilkinson was one of the most duplicitous, avaricious, and altogether corrupt figures in the early history of the United States. At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, he was a paid agent of the Spanish government.

Until he presented his services to General Washington at Valley Forge, the Continental Army still consisted merely of a number of state-sponsored militias that were entirely independent of one another, each operating according to its own rules and regulations.

There may have been one good personal reason why Clark carried an umbrella. Beneath our skins we’re all supposed to be pretty much alike, but at the epidermal level there are some conspicuous differences that we owe to melanin.

September 10, 1806

News of Zebulon Pike

Fur traders heading up the river tell the captains that Zebulon Pike is leading an expedition to the source of the Arkansas River. They end the day near present Bean Lake, Missouri.

Its oak-strong, hickory-tough wood made powerful, reliable hunting bows. Early French explorers and traders translated its Indian name into bois d’arc,–”wood for a bow,” which was easily anglicized into “bodark.”

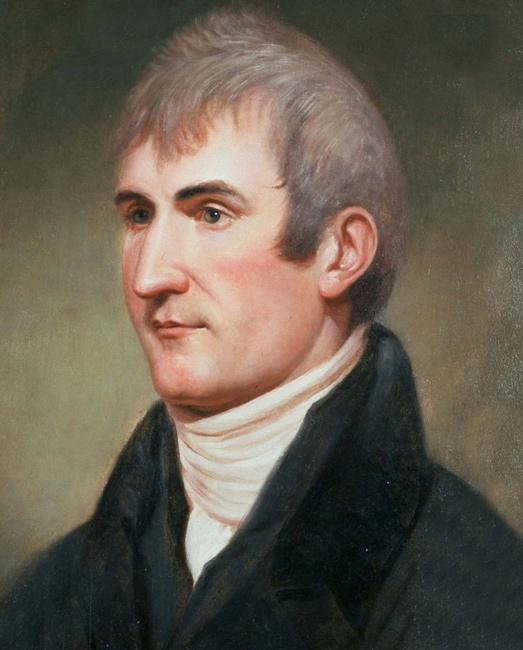

Born on 18 August 1774, he was exactly eight months old when Paul Revere made the legendary ride that signaled the beginning of the War of Independence, and the birth of the new United States of America, which Lewis was to serve with distinction.

Lewis had no reason to write about the common or fallow deer of the East Coast, although in using it for the purpose of comparison, he gave quite a clear picture of it. John Godman’s 1828 description relied partly on Lewis and Clark’s journals.

“accedentaly the ball passed through the hat of a woman about 40 yards distanc cutting her temple about the fourth of the diameter of the ball.”

The Louisiana Purchase

by Pierce Mullen

Easter week in Paris, 1803, was truly momentous for the young United States of America. The American Minister to France, Robert R. Livingston was sent to discuss the difficult question of New Orleans, the Mississippi and Franco-American relations.

February 28, 1803

Philadelphia mentors

In Washington City, President Jefferson signs the bill authorizing what would become the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He asks Dr. Benjamin Rush and Caspar Wistar to help Lewis while he is in Philadelphia.

McKean, Pennsylvania governor, was the first pro-Jefferson, anti-Federalist governor in the nation. As Pennsylvania chief justice, he assumed it the right of the court to strike down legislative acts it deemed unconstitutional.

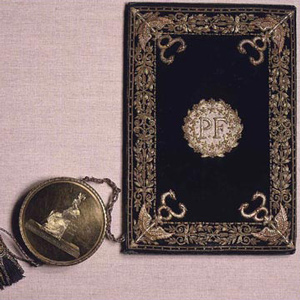

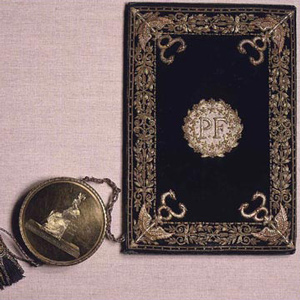

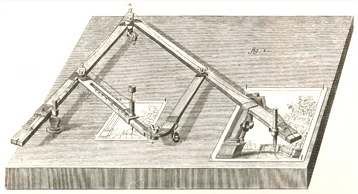

Profile Portraiture

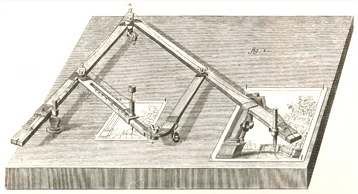

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In 1802 the British-born Philadelphian, John Isaac Hawkins (1772-1805)5, invented a new kind of copy machine, a pantograph with which a person could produce a miniature copy of his or her profile through direct contact. He called it a physiognotrace.

Early American Entomology

by Joseph A. Mussulman

There were only four notable 18th century naturalists who showed much interest in America’s insects: a young Englishman named Mark Catesby, Finnish botanist Peter Kalm, Philadelphian William Bartram, and Reverend Frederick Melsheimer of New Hampshire.

Rush was the most famous physician in America in 1803, the year Meriwether Lewis, at the behest of Thomas Jefferson, visited him in Philadelphia, where Rush would advise Lewis on how to keep his men healthy.

Drouillard spotted the first “Deer with black tales” on 5 September 1804, on the cliffs upstream from the mouth of the Niobrara River in northeast Nebraska. By 10 May 1805 Lewis had seen enough specimens to write an 800-word description of the new species.

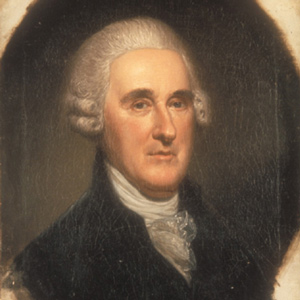

Portraits of William Clark

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Four portraits and one statue by five different artists show a diverse interpretation of the likeness of William Clark.

Clark shot “a Prarie Wollf, about the Size of a gray fox bushey tail head & ear like a wolf.” Lewis wrote his description of what proved to be a new species on 5 May 1805, in northeastern Montana.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.