We Proceeded On, is the official publication of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, the sponsor of this website. Its name derives from a phrase that appears repeatedly in the collective journals of the expedition.

This Arikara leader rode upriver with the expedition in the weeks that followed to negotiate a peace settlement with the Mandan. In the spring of 1805 he went down river with the barge to St. Louis. After a series of delays, he went to Washington, DC, to meet with President Jefferson.

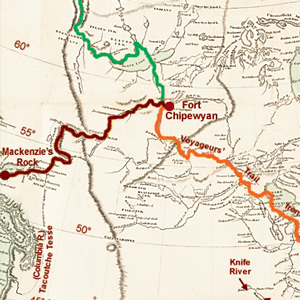

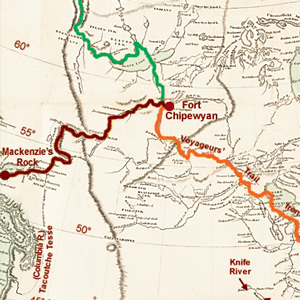

He was the first literate traveler to cross the North American continent north of Mexico, beating Meriwether Lewis and William Clark by nearly 12 years. The Lewis and Clark journals often echo Mackenzie’s journal.

Columbia River Basalts

by John W. Jengo

The region of the lower Snake River and the Columbia River’s course through the Columbia Plateau and Gorge experienced volcanic activity starting some 55 million years ago, although the expedition would primarily encounter rock units of Miocene-age.

Columbia Gorge Waterfalls

by John W. Jengo

William Clark: “Saw 4 Cascades caused by Small Streams falling from the mountains on the Lard. Side.”

Phoca (Seal) Rock

by John W. Jengo

The mid-river island identified as “Phoca” and “Seal rock” on one of William Clark’s route maps is a compact landslide block that detached from the Cape Horn headland.

The members of the expedition began their journey as a wild bunch of hard drinking, brawling, and insubordinate rowdies. By 7 April 1805, the day the Corps of Northwestern Discovery pulled out of Fort Mandan, Lewis described his men as enjoying “a most perfect harmony.”

The 21 October 1805 rock fall geologic notation is likely referring to mass-wasting features along a fourteen-mile long stretch of dramatically steep slopes visible today between Blalock Canyon and the John Day River.

After the night of 3 June 1804, just past the Moreau River in present-day Kansas, Clark and Ordway reported that a loud bird sang all night. They called it a nightingale, but no such species lives in North America. Just what type of bird did they hear?

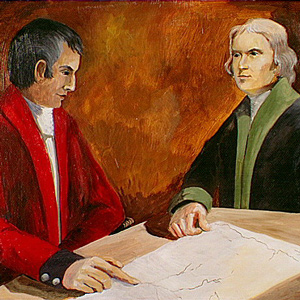

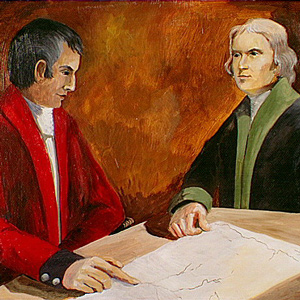

The President’s Secretary

by Arlen J. Large

It was 4 March 1801, Inauguration Day for the third president. Nine days previously Jefferson had asked Meriwether Lewis to serve as his private secretary in the raw new mansion called the President’s House.

The jolly men of Lewis and Clark danced their way into history—a fascinating look behind the “big scenes” of America’s intriguing Corps of Discovery.

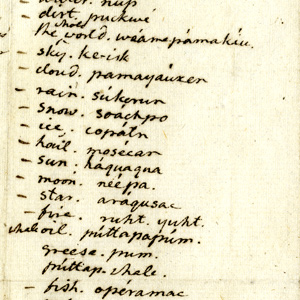

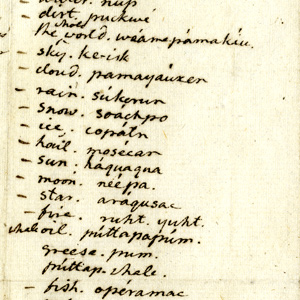

The Indian Vocabularies

by Bob Saindon

Due to the many unfortunate events which followed Lewis’s death, in 1809, the Indian vocabularies the captains had carefully collected are now lost, and were never made available to the public.

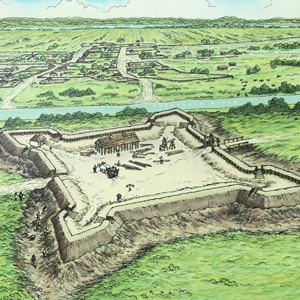

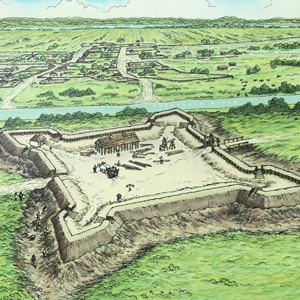

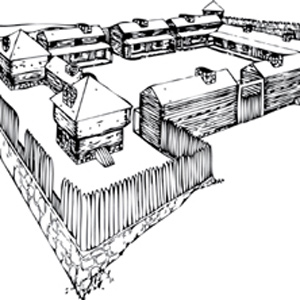

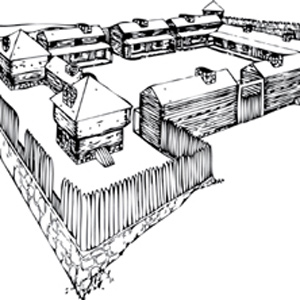

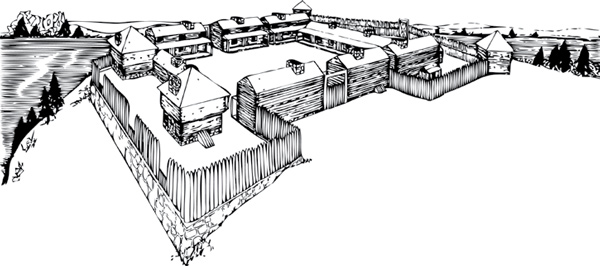

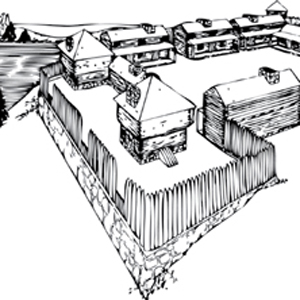

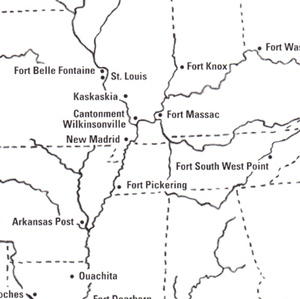

Fort Kaskaskia

Preliminary outpost

Archaeological investigations by the author and his students reveal the location of the American Fort Kaskaskia. Extracts from “Bound to the Western Waters: Searching for Lewis and Clark at Fort Kaskaskia, Illinois” by the lead archaeologist.

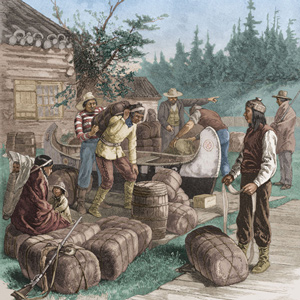

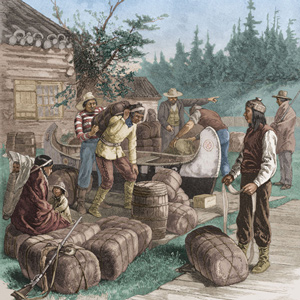

Sugaring at River Dubois

Surrounded by maple trees at Camp Dubois, tapping and boiling the sweet, watery sap until it crystallized into sugar could begin as soon as the days warmed enough to get the sap rising in the trees.

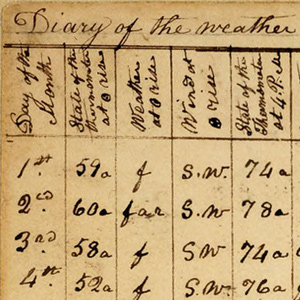

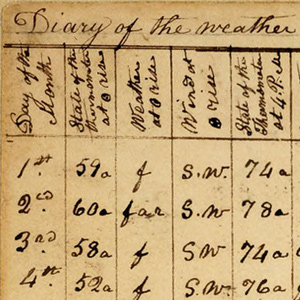

President Jefferson naturally was curious about weather conditions in the newly acquired expanse of Louisiana, and weather observations were on the long list of assignments for his exploring team. Jefferson instructed Lewis to record climate data observed on the trip.

The spare vocabulary of the busy journalists was spiced here and there with the clichés and colorful sayings of the time. That vocabulary itself is another valued legacy of the 1804–1806 expedition.

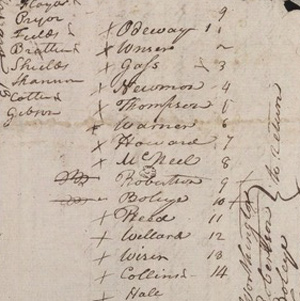

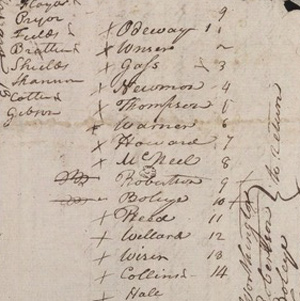

Ohio River Recruits

by Arlen J. Large

Dearborn gave the departing Lewis an order limiting his permanent size to 15 men. These soldiers also were to be obtained at Kaskaskia and other Illinois Army posts, or newly recruited into the Army from “suitable Men” encountered by Lewis along the way.

Antoine Saugrain

by Robert R. Hunt

Called the “First Scientist of the Mississippi Valley,” Saugrain was a chemist and naturalist and the only physician in the frontier community of St. Louis when Lewis and Clark arrived there.

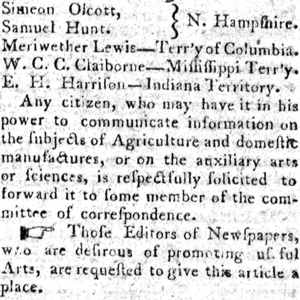

Lewis and the Board of Agriculture

by Arlen J. Large

As the President’s private secretary, the 28-year-old Army captain wasn’t in the same league with the political heavy-weights on the new American Board of Agriculture.

Moving between Philadelphia and Washington City in 1803, Lewis devised a plan for recruiting personnel while traveling to St. Louis. Plan A was to go down the Cumberland River, Plan B, the Ohio.

Several anxious moments on the trail were associated with an implement which Lewis referred to in his journal as an “espontoon,” i.e., a half pike commonly carried by an eighteenth century infantry officer.

The Permanent Party

by Arlen J. Large

Between St. Louis and the Pacific Ocean, and on the return to St. Louis, personnel decisions needed to me be made.

Lewis writes: “the bier in which the woman carrys her child and all it’s cloaths wer swept away as they lay at her feet she having time only to grasp her child.” This bier, then, is a bar or net serving to keep mosquitos from one’s personal blood supply.

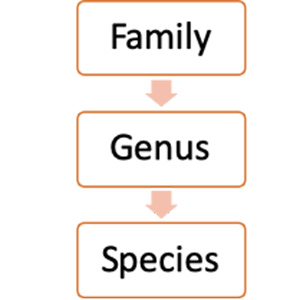

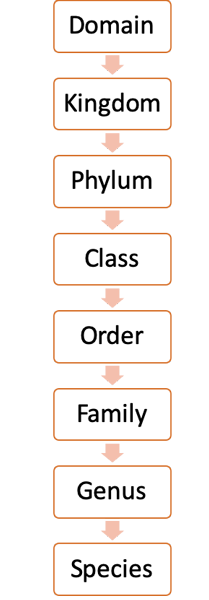

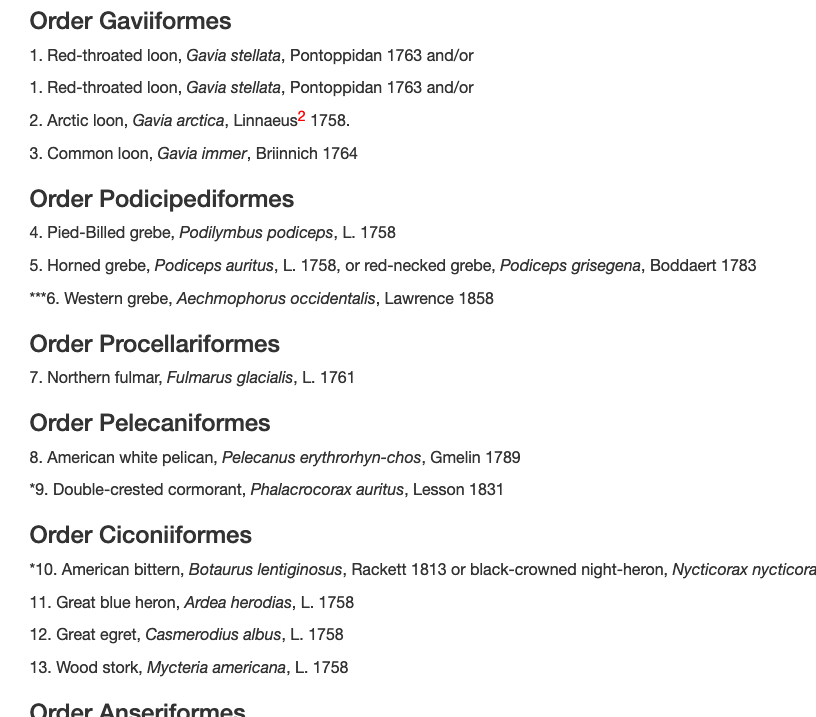

In 1758, the great Swedish classifier Carl Linnaeus urged every scientist to give join him in using a universal and simplified system of classification. He had just published a new text re-naming every plant and animal he knew with a two-word Latin label—a binomial.

Ignorant of plains politics, Lewis and Clark barely averted disaster in their encounter with Black Buffalo’s people—an article by James P. Ronda from a keynote address to the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Pierre, South Dakota, August 2002.

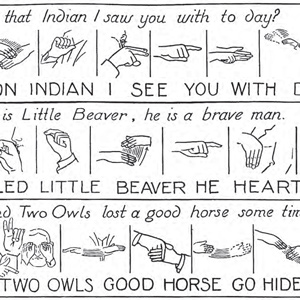

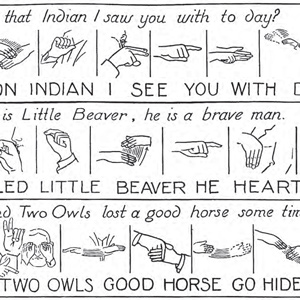

“our guide could not speake the language of these people but soon engaged them in conversation by signs or jesticulation, the common language of all the Aborigines of North America.” Lewis exaggerated the universality of sign language, which was mainly employed by tribes of the Great Plains.

Prior to the Lewis and Clark Expedition, William Clark and Meriwether Lewis began their military careers by actively serving in their local militias. After that, they joined the regular army and first met during the Ohio Valley’s Indian wars.

In the 1750s the British Navy had begun issuing 50 pounds of portable soup for every 100 sailors on long voyages, partly to vary the daily diet of salt-cured meats, and partly in the mistaken belief that it would prevent scurvy.

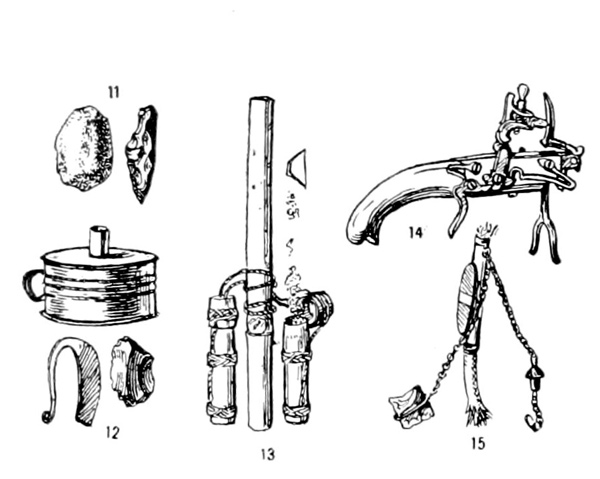

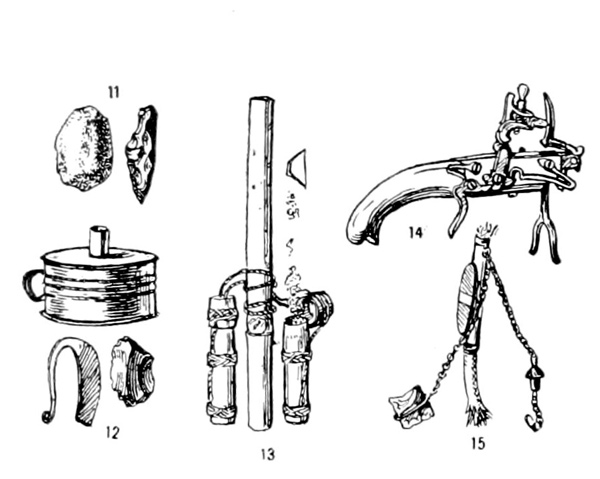

How did the Indians, expedition cooks, and the hunters make fire? Several methods were used.

The expedition left horse tracks of at least four to five hundred miles on a westward lineal course, plus at least a thousand miles easterly, widely scattered over strikingly varied terrain. The Corps of Discovery had become, in effect, a kind of cavalry unit.

Thermometers and Temperatures

by Robert R. Hunt

President Jefferson held a long-term interest in climate and thermometers and recording climate data was included in his instructions to Lewis. Where Lewis obtained his thermometers and why the temperature on so many days days went unrecorded remains a mystery.

“the Ocian is imedeately in front and gives us an extensive view of it from Cape disapointment to Point addams,” reported William Clark on 15 November 1805. But he saw no ships at anchor. Nothing.

Lewis and Clark as Ethnographers

by James P. Ronda

As ethnographers, the captains provided “names of the nations & their numbers” and recorded the strange cultures they encountered. Their work as ethnographers is examined here by James Ronda.

Lewis knew before embarking on his mission that there would be a pack of fish in his future. In Philadelphia in the summer of 1803, preparing for the expedition, he visited the “Old Experienced Tackle Shop” kept by George R. Lawton, a dealer in “all kinds of Fishing Tackle for the use of either Sea or River.”

Unaccountable ‘Artillery’ of the Rockies

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Near the Great Falls, Lewis describes loud noises “resembling precisely the discharge of a piece of ordinance of 6 pounds at the distance of three miles.” Thunder didn’t seem likely as “It was perfectly calm, clear, and not a cloud to be seen.”

Near Wallula Gap, Meriwether Lewis apparently collected an enigmatic and long-missing mineral specimen that was never documented in the expedition journals.

On 22 December 1803, Drouillard arrived at Clark’s Camp Dubois with the eight lost soldiers from South West Point. They were a disappointing lot, except for Corporal Richard Warfington.

Clark’s affection for Sacagawea’s little boy, Jean Baptiste, becomes evident while canoeing down the Yellowstone River. This article analyzes Clark’s offer to his father, Toussaint Charbonneau, to raise the child.

Cameahwait’s Geography Lesson

by J. I. Merritt

When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark encountered the Shoshone Indians in August 1805, one or the other—or more likely both, sat down with Cameahwait, the chief of the tribe’s Lemhi band, to learn as much as possible about the region’s geography.

The explorers assembled the iron-framed boat in the early summer of 1805 at the Upper Portage Camp, upstream of the Great Falls. There Lewis and the men put together the frame. “We called her the Experiment,” wrote Sergeant Patrick Gass.

The Missouri River exposed rock formations that were geologically diverse, distinctly colored, rich in mineral content, and in some places, dramatically distinguished by steaming and smoking hot earth that beckoned to be investigated.

The Charbonneaus in St. Louis

by Robert J. Moore

In 1809, Toussaint, Sacagawea, and Jean Baptiste Charbonneau traveled to St. Louis. Jean Baptiste’s baptism began a new era in his life, is father would try to become a farmer, and Sacagawea would become sickly.

Lewis’s letters reveal a fastidious quartermaster, a meticulous project director, an exceptional logistics manager and a superb bureaucrat who was scrupulously devoted to detail. Lorna Hainesworth unravels the eastern travels of Meriwether Lewis between March and July 1803 using a letter that she uncovered in 2009.

A Submerged Forest

by John W. Jengo

On 30 October 1805, Clark documented the presence of a submerged forest, which along with the burning bluffs of northeastern Nebraska, the “Burnt Hills” of North Dakota, and White Cliffs of the Missouri in central Montana, remain one of the expedition’s most famous geological observations.

Next to grizzly bears and Mother Nature, the most feared enemy of American fur trappers traveling along the upper Missouri River were the Niitsítapi or Blackfeet, the “Original People” or “Prairie People.” Was that Lewis’s fault?

One of the animals recorded by Lewis and Clark—and which became one of the staples of their mostly carnivorous diet—was the wapiti, or American elk (Cervus elaphus).

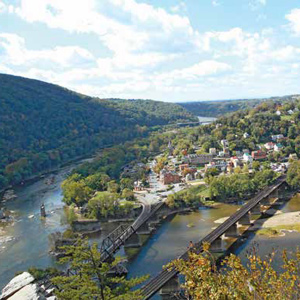

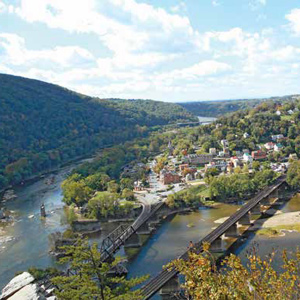

During preparations, Lewis relied on the Harpers Ferry Armory and Arsenal for the guns and hardware that would meet his unique requirements.

Summary of Birds Seen

by Virginia C. Holmgren

The birds seen on the expedition are listed by scientific order and numbered for a total of 134 species or well described subspecies. Each is identified by Latin binomial (trinomial for subspecies), surname of original classifier, and year of publication.

The expedition traveled out from under an ancient river channel frozen in time to a river discharging huge volumes of sediment in real time, the “quicksand river,” now known as the Sandy River.

The Lemhi Shoshones

by Stephen E. Ambrose

The Lemhi Shoshones were the first Indians they had seen since leaving the Hidatsas and Mandans. In describing them, Lewis was breaking entirely new scientific ground. His account is therefore invaluable as the first description ever of a Rocky Mountain tribe, in an almost pre-contact stage.

The St. Charles Boatmen

by Jo Ann Brown-Trogdon

The earliest baptism, marriage, and burial registers of St. Charles Borromeo parish help explain the identities and family connections of several of the french boatman from St. Charles.

Joseph Gravelines

by Clay S. Jenkinson

The Arikara-resident trader and interpreter Gravelines proved to be so reliable and so good at the immediate tasks put to him that long after the Lewis and Clark Expedition he was employed by the United States government to represent its interests among the Arikara.

While in Philadelphia in the summer of 1803, Lewis clearly had foreseen the rigors of weather which would be encountered on a planned two year “campaign.” He carefully provided, as any military commander would, for appropriate protection for his soldiers.

The story behind Charles M. Russell’s 1912 painting of the expedition meeting the Bitterroot Salish at Ross’ Hole, one of the great works of Western American art.

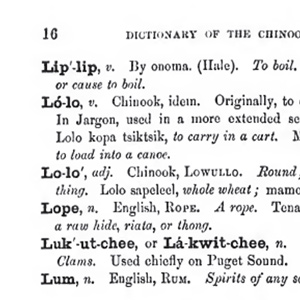

Lewis and Clark appear to have been unaware of the existence of Chinook Trade Jargon. Never-the-less, some of the words they encountered would be later documented as part of the jargon.

As Secretary of War during the expedition, Henry Dearborn made several decisions critical to the it’s success, and he was the one who gave Clark’s the military rank of lieutenant.

Private Whitehouse and Sergeant Gass recorded that passing Indians told of a whale washed ashore south along today’s Oregon coast. Several days later, Clark set out with twelve men in two canoes to trade for as much blubber as their small amount of merchandise would allow.

In this brief extract from We Proceeded On, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Carol MacGregor explains the beginning and purpose of the American Philosophical Society and its connection to the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Birdwatcher’s Guide to Lewis and Clark

by Virginia C. Holmgren

As you find each one and try to check each identifying clue, you cannot help but know much of the same challenge, the same success—or frustrations—that kept Lewis and Clark birdwatchers to the end.

What happened to this famous Newfoundland dog? Did he complete the expedition? Or did he perish somewhere along the Missouri River? Was he with Lewis when at Grinder’s Stand?

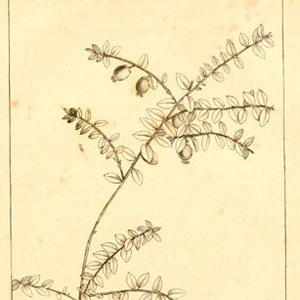

Columbia plateau biscuitroots: “one of the grateful vegetables” by naturalist Jack Nisbet. An Indian food source for thousands of years.

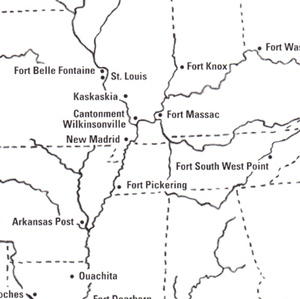

Fort Southwest Point, a frontier garrison in eastern Tennessee during the late 1790s and early 1800s, played an important role in the planning for and recruitment of soldiers for the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Although not nearly as celebrated as their botanical and zoological work, Lewis and Clark collected a multitude of mineralogical specimens throughout the expedition.

During the planning and preparations for the Western Expedition, Thomas Jefferson practiced selective levels of secrecy.

Geology of The Dalles

by John W. Jengo

Over four days (22-25 October 1805) the expedition would be navigating through one of the most exciting and difficult stretches of the entire water route to the Pacific. Several outstanding geological features were noted.

The consolidated rocks that compose the Gorge were formed by a complex interplay of Columbia River Basalt Group flood basalt deposition and basin subsidence, along with contemporaneous folding and faulting—not the Glacial Lake Missoula floods.

No military commander of the 18th-century would have thought of leading his troops on any mission without planning for liquor. In legislation and military orders of the day, the ration was typically expressed in “gills.”

In 1804 and in the presence of the Lewis and Clark expedition the little village, built and designed to be an outpost of the fur trade, shed its ambiguous Spanish-French parentage and took on full American citizenship.

From the moment they dipped their paddles into the Snake River, the Lewis and Clark expedition would not only be following the path of multiple flood basalt flows, but also the route of the colossal Lake Missoula floods that so markedly scoured the basaltic landscape.

In 1792, André Michaux approached members of the American Philosophical Society informing his potential sponsors that he was “ready to go to the sources of the Missouri and even explore the rivers that flow into the Pacific Ocean.”

We may never know the full historical impact of Lewis and Clark’s discoveries upon nineteenth-century scientific inquiry, but this example highlights how just a series of conversations with the returning explorers allowed a significant earth science discovery to be revealed to the scientific community.

Army Life and Leadership

by Sherman L. Fleek

Retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel and former chief historian of the National Guard Bureau discusses frontier army life in 1803 and the exemplary military leadership of the co-captains and non-commissioned officers.

As a professional geologist and a Lewis and Clark enthusiast I’m impressed by what the captains had to say about the geology of the Upper Missouri River Breaks, as suggested by the following journal excerpts and commentary.

They didn’t get credit for it, but Lewis and Clark were the first to describe these wily canine predators.

Rooster Rock at Crown Point

by John W. Jengo

The promontory of Crown Point comes to mind when Clark mentions in his notebook journal that the expedition camped “under a high projecting rock.”

Six years before signing on with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, George Drouillard took part in a sensitive international mission for the United States Army. This mission was probably just one of Drouillard’s many services to the United States in the last decade of the eighteenth century.

This glossary lists in alphabetical order the bird names used by Lewis and Clark in expedition records. To aid the reader in locating a complete passage in any edition of the journals, or paraphrase based on the original journals, each bird name is followed by the date of usage—usually the first, or a later significant, entry.

The relatively uncomplicated sound key of the expedition itself can readily be imagined. The natural soundscape of the expedition’s trail is harder to reconstruct.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.