Another Entry in the Chapter of Accidents

© 2000 by Michael Haynes. All rights reserved.

On two occasions during the expedition Lewis either explained or resolved problems by consigning their outcomes to the “chapter of accedents.” The expression came from a sentence in a popular book by the British memoirist Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield (1694-1773). Lord Chesterfield wrote to a friend in 1753 in reference to his own growing deafness: “The chapter of knowledge is a very short, but the chapter of accidents is a very long one. I will keep dipping in it, for sometimes a concurrence of unknown and unforeseen circumstances, in the medicine and the disease, may produce an unexpected and lucky hit.” Lewis, however, used the aphorism more often in connection with a near calamity than with a “lucky hit.”[1]John Bradshaw, ed., The Letters of Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield, 3 vols., (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1892), 3:1054.

By the time he first used the phrase on 15 July 1806 when McNeal broke his musket clubbing a grizzly, Lewis had seen many accidents. At this late stage in the expedition, he seemed resigned to the all too common close calls and frustrating setbacks. When Lewis didn’t find Clark at the mouth of the Yellowstone on 8 August 1806, he used the phrase one more time. He did not, however, apply it three days later when Cruzatte accidentally shot him in the buttocks, perhaps his most perilous near miss.

Selected Accidents

May 14, 1805

Two close calls

In present Eastern Montana, hunters take flight from a wounded grizzly and the white pirogue, steered by Toussaint Charbonneau, tips over. The captains call it a day and issue a ration of consoling grog.

May 23, 1804

Lewis escapes death

Lewis climbs the pinnacles of Tavern Rock, slips, and manages to escape with the help of his knife. In Tavern Cave, Clark adds his name among the graffiti left by earlier travelers.

At 3 o’clock in the afternoon, 11 September 1805, Toby led the Corps of Discovery out of Travelers’ Rest camp toward the Bitterroot Mountain barrier.

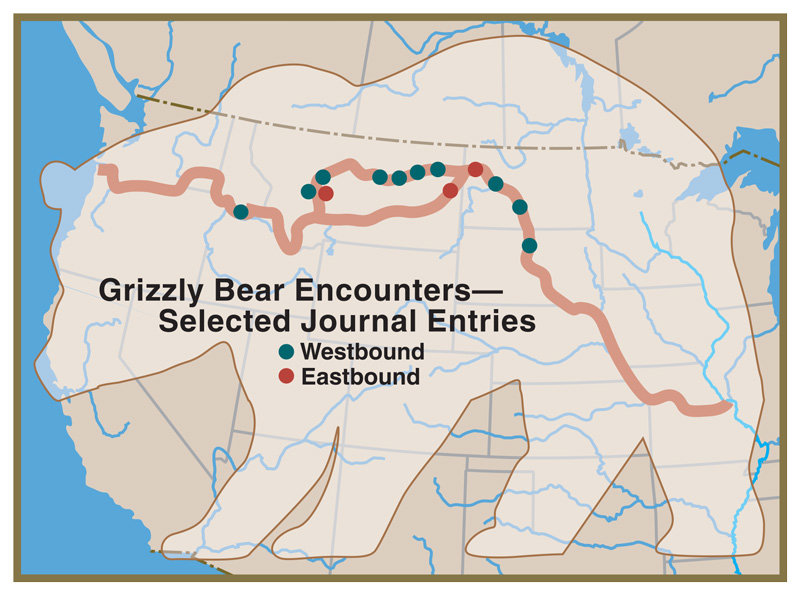

“the Indians give a very formidable account of the strength and ferocity of this anamal, which they never dare to attack but in parties of six, eight or ten persons; and are even then frequently defeated with the loss of one or more of their party.”

Of all the near-calamities the Corps of Discovery experienced, none was more dire than the one that occurred on 29 June 1805 in a normally dry ravine a short distance above the Great Fall. The principals were Charbonneau, Sacagawea, Jean Baptiste, York, and William Clark.

August 6, 1805

Down the Big Hole

Clark learns he is on the wrong river and turns the dugouts around. In going down the Big Hole, Pvt. Whitehouse is nearly crushed. They camp at the forks of the Jefferson River to dry items and recover.

Lewis’s simple, orderly concept of the Rocky Mountains began to crumble. The truth was, this was not the easy portage to the Pacific Ocean they had expected from the beginning. Countless “chains” of mountains still intervened.

Pryor and six privates had successfully driven forty-one horses all the way to the Yellowstone Valley, apparently without any trouble. Then, smoke on the horizon. Twenty-four horses stolen on the twentieth. Seventeen taken on the twenty-fifth.

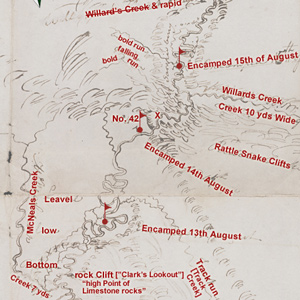

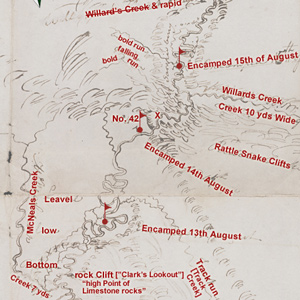

August 8, 1806

Sgt. Pryor catches up

In the morning, Pryor arrives at Clark’s camp having paddled two bull boats down the Yellowstone River. Lewis sets up a camp near present-day Williston to make clothes, repair boats, hunt, and make jerky.

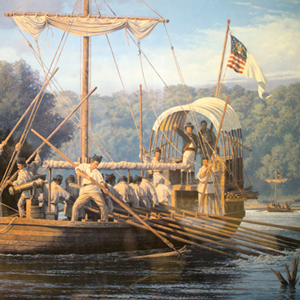

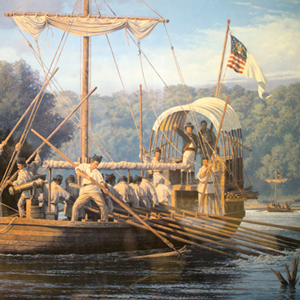

June 9, 1804

Hitting a snag

After passing Arrow Rock, the barge hits a snag and turns sideways to the current exposing it to logs drifting in the strong Missouri current. The men struggle to get her off before she is injured.

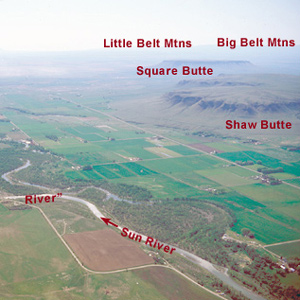

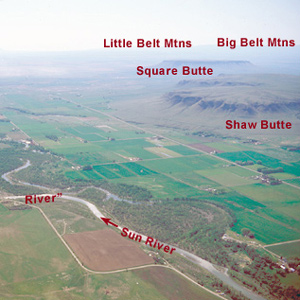

One can almost feel the thrill of wakening to a clear early-summer dawn at this powerful place on the pregnant plains where the Medicine meets the Missouri. Here began a five-day hiatus in Lewis’s master plan for his junket to find the boundary of British-held Canada.

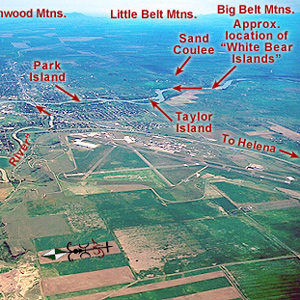

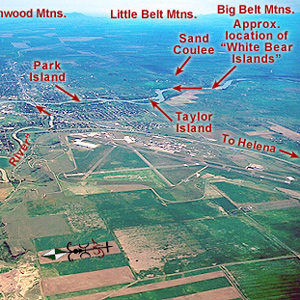

Down the Sun River

Through the "Battle Hills"

Meriwether Lewis has tempted fate and his “chapter of accidents” again by re-entering the domain of the people he had repeatedly been advised to steer clear of—the Blackfeet, Siksikas, Atsinas, and Assiniboines.

“This smoke must be raisd. by the Crow Indians in that direction as a Signal for us, or other bands. I think it most probable that they have discovered our trail.”

June 21, 1804

Camden Bend difficulties

In passing an island around present-day Camden Bend, Missouri, Clark feels fortunate that only one barge window was broken and some oars lost. He also describes the trees growing in the bottomlands.

August 11, 1806

Cruzatte shoots Lewis

Lewis is shot through the buttock. An Indian attack is suspected, but likely Pvt. Cruzatte mistook him for an elk. Clark meets fur traders who share news of the barge, the fur trade, and Indian wars.

The most serious hunting mishap, and surely the most memorable episode in Lewis’s frequently referenced “chapter of accedents,” was the moment on 11 August 1806 when Pierre Cruzatte shot him in the buttocks.

Notes

| ↑1 | John Bradshaw, ed., The Letters of Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield, 3 vols., (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1892), 3:1054. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.