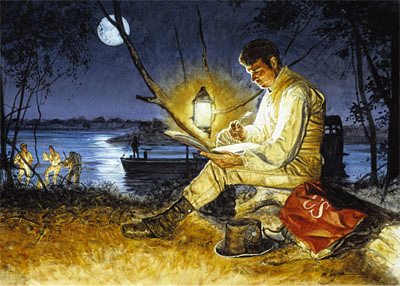

“In this moonlight scene on the Missouri River 1804, Sgt. John Ordway writes of the day’s events in his journal. One of the expedition’s fiddlers, perhaps Pierre Cruzatte, provides a bit of lively music . . .”[1]Robert Moore, Jr. and Michael Haynes, Tailor Made, Trail Worn: Army Life, Clothing, & Weapons of the Corps of Discovery (Helena: Farcountry Press, 2003), 106.

The Call of Duty

John Ordway seems to have been the most solid hand among the enlisted men. His journal is the only one carries an entry for every one of the trek’s 863 days—beating even William Clark‘s record.[2]Moulton, ed.,Journals, 2:514. Ordway seldom reveals personalities or personal emotion in his often-detailed entries, but the very last words of his journal hint at the man’s priorities:

[23 September 1806] about 12 oClock we arived in Site of St. Louis fired three Rounds as we approached the Town and landed . . . the people gathred on the Shore and Huzzared three cheers . . . the party all considerable much rejoiced that we have the Expedition Completed and now we look for boarding in Town and wait for our Settlement and then we entend to return to our native homes to See our parents once more as we have been So long from them.—— finis.

Even then, duty still called and Ordway went to Washington, D.C., with the group including Lewis and Chief Sheheke’s delegation before being discharged and heading home to New Hampshire. In addition to visiting family, Ordway married a woman named Gracey. The couple moved to Missouri in 1807, settling at New Madrid (pronouncedMAD-rid) on the Mississippi River just north of the Kentucky-Tennessee border.

Just after the expedition ended, Ordway had purchased the land warrants issued to Jean-Baptiste Lepage and William Werner. Combining them with his own warrant and additional purchases, Ordway soon was raising horses and cattle on 1,000 rich acres. Three of his siblings, and their families, also moved to the area. The year following Gracey’s death in 1808, Ordway married the widow Elizabeth Johnson.

The former sergeant’s prosperity ended late during the winter of 1811-1812, as it did for everyone living in the New Madrid area. Earthquakes on 16 December, 23 January, and 7 February—centered on the New Madrid Fault under the Mississippi River—were the 7th, 10th, and 21st largest, respectively, in United States history.[3]http://earthquake.usgs.gov/regional/states/10_largest_us.php/ (For comparison, the 1906 San Francisco quake was the 19th largest. Scientists project that a quake like the New Madrid series today, which is entirely possible, would destroy 60% of Memphis, Tennessee.) For some moments, the Mississippi River famously flowed upstream. Water and sand geysered from the earth as high as treetops, and crashed down on houses. Topsoil dropped into sinkholes, and lakes formed where crops had grown. Buildings collapsed. The shocks were felt as far away as New York and Kansas.

Ordway and his family apparently continued in poverty until his death—although he certainly had learned during the expedition how to live lightly. In February 1818, Elizabeth initiated probate proceedings for the estate of “John Ordway, Deceased.”

Trouble at Camp Dubois

Although John Ordway did not enlist formally for the expedition until January 1, 1804, he was at Camp Dubois before that. He had volunteered from Capt. Russell Bissell’s company at Fort Kaskaskia, and was the Corps’ only sergeant with previous army experience. Lewis made Ordway’s position clear in Detachment Orders dated 20 February 1804:

The commanding officer directs that during the absence of himself and Capt. Clark from Camp, that the party shall consider themselves under the immediate command of Sergt. Ordway, who will be held accountable for the good poliece and order of the camp during that period . . . .

In Lewis’s Detachment Order of 4 April 1804, which established the three sergeants’ squads, Ordway was placed permanently in charge of the duty roster.

On the Trail

Underway on 4 June 1804, a favorable breeze allowed putting up the barge‘s (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) sail in present Cole County, Missouri. Ordway was steering it alone near the bank when a rope attached to the mast got hung up in a sycamore tree[4]Ordway’s 1804 journal is filled with the names of tree species seen along day after day, and he duly specified the type of culprit here. “& it [the mast] broke verry Easy.” He confessed in his own journal to being the man at the rudder; Clark in his journal simply let the identity go with “the Sergt. at the helm.”

Ordway went with Clark on the 1806 return as far as the Three Forks of the Missouri. There, he took charge of John Collins, John Colter, Pierre Cruzatte, Thomas Howard, Jean-Baptiste Lepage, John Potts, Peter Weiser, John Whitehouse, and Alexander Willard and several canoes. Leaving on 13 July 1806, they paddled quickly downstream to White Bear Islands upstream from the falls, which they reached on 19 July 1806. Headwinds and fierce mosquitoes plagued the trip, with the taciturn sergeant even mentioning that “the Musquetoes and Small flyes are verry troublesome. my face and eyes are Swelled by the poison of those insects which bit verry Severe indeed.”[5]Moulton, 9:337. Ordway and his men joined Sgt. Patrick Gass‘s men (who had gone with Lewis to that point) in portaging baggage around the falls.

That chore completed on 27 July 1806, they proceeded down the Missouri to the mouth of the Marias River, where they were assigned to open the caches and await Lewis and the men he had taken to explore the Marias’s headwaters. The very next morning, before reaching the Marias:

we discovred on a high bank a head Capt. Lewis & the three men who went with him on horse back comming towards us on N.Side we came too Shore and fired the Swivell to Salute him & party[.] we Saluted them also with Small arms and were rejoiced to See them &c. Capt. Lewis took us all by the hand and informed us . . .

Lewis informed them of the success and failure of his side trip, and his fear that Blackfeet warriors might be on his path. Besides recording the joyful reunion, Ordway recounted the story of Lewis’s fight with the Blackfeet in rare detail.

A week later, it was Ordway to Willard’s rescue. The two had been hunting and were canoeing down the Missouri to rejoin Lewis and the others, when sawyers (submerged trees) snagged their boat. Willard was dumped out and had to cling to the sawyers. Ordway got the boat to shore as soon as he could, and ran back half a mile to help his partner.

Cruzatte’s accidental shooting of Lewis on 11 August 1806 drew another unusually expansive journal entry from Ordway. But he wrote that “we dressed the wound,” while Lewis’s said that “with the assistance of Sergt. Gass I took off my cloaths and dressed my wounds myself as well as I could.”

When the Corps picked up Chief Sheheke and his family to travel back with them and on to visit President Jefferson, Ordway recorded the scene. It gives modern readers a hint of the fear engendered by such a state visit into the unknown

. . . the chief putting his arm around all the head mens necks of his nation who Set on Shore and a number crying and appeared Sorry to part with him . . . .

After seeing Sheheke and his party safely to the President’s House, Ordway would be on his way home to his own family in New Hampshire.

Principal Source

Post-expedition information is drawn from Larry E. Morris,The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 102, 104, 196.

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert Moore, Jr. and Michael Haynes, Tailor Made, Trail Worn: Army Life, Clothing, & Weapons of the Corps of Discovery (Helena: Farcountry Press, 2003), 106. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Moulton, ed.,Journals, 2:514. |

| ↑3 | http://earthquake.usgs.gov/regional/states/10_largest_us.php/ |

| ↑4 | Ordway’s 1804 journal is filled with the names of tree species seen along day after day, and he duly specified the type of culprit here. |

| ↑5 | Moulton, 9:337. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.