Editor’s Note

By WikiCommons user curtisbellis. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

Above: a pirogue with painted washstrakes.

What should the red and white pirogues of the Lewis and Clark Expedition look like? We know they were larger than the many dugout canoes built along the way. They were typically rowed, not paddled or poled, and they had sails and rudders. Most historical interpretations, including those shown on this page, have them looking like large rowboats made from wood planks. Most writers before, during, and after the expedition consistently used pirogue to mean a dugout, a boat carved from a singular tree in the manner of indigenous peoples throughout North and South America. To the dugout’s hollowed-out log could be added seats, washstrakes, thole pins or iron oarlocks, a sail, and rudder. Their color could be from the source tree—white from the tulip poplar, red from the cypress—or they could have been painted. The above pirogue’s outboard motor has eliminated the need for a rudder, sail, and oars.—KKT, ed.[1]John W. Fisher, “The Pirogue,” Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly 48, no. 3 (Fall 2012): 1–13. See also Mark W. Jordan, “Watercraft of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A … Continue reading

Deep in the murky currents of nautical history lay the dim outlines of the many different types of watercraft that were afloat on North American waterways in the first two decades of the nineteenth century. For the most part, their identifiable shapes, dimensions, and uses have long since fallen away from the wood, canvas, rope, and metal fittings that once differentiated them—the flat boat, broadhorn, bateau, galley, keelboat, gundalow, canoe, barge, pettyauger, Schenectady boat, and many more.[2]The classic study of boats that were used in America between Colonial times and the end of the nineteenth century, in which more than sixty distinct types and designs are described and illustrated, … Continue reading Aside from the very detailed drawings of the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) that Clark left us, we remain in the dark as to the structural details of the other watercrafts the Corps of Discovery used–two large rowboats with sails, which they usually called pirogues;[3]In northern urban America the pronunciation is pi-rogue (with a long o in the accented second syllable, and a hard g as in go pronounced backwards). Down in Mississippi and Louisiana the 17th century … Continue reading a total of thirteen dugout canoes that they carved themselves, plus two Indian-made canoes they acquired (one they “took,” the other they bought) on the lower Columbia. The Corps also used at least three bull boats and a raft.

In addition, they carried the hardware to be assembled into Meriwether Lewis‘s hide-covered iron-framed boat. Lewis had designed it for use as the expedition’s main cargo conveyance on the upper reaches of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers; the frame would be dismantled for the expected portage between the headwaters of the two rivers, and covered again with hides on the other side. When the Great Falls of the Missouri proved to be as far as they could go with the larger of their two pirogues, the only option was to switch to Lewis’s “favorite boat.” But owing to several misjudgments on Lewis’s part, his “experiment” failed, and to take its place the men had to carve two more dugout canoes.

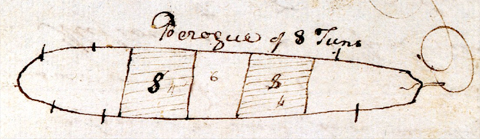

This article deals with the two pirogues that served as supplementary cargo carriers accompanying the barge from the mouth of the Missouri to the Knife River Villages, one of which became the command boat on the return trip from the Marias River to St. Louis. Clark left us only a rough sketch of one of them (Figure 3), evidently drawn in haste, possibly to illustrate some point he was trying to make with the men in command of the two pirogues about how, and how much, they were to be loaded. With this sketch, plus the crew assignments for each of the three outbound boats, some passing remarks in the journals, and consideration of what is known about the history of small crafts in America, it has been possible for nautical historians such as Richard Boss to create reasonable replicas.[4]Richard Boss, “Keelboat, Pirogue, and Canoe: Vessels Used by the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery,” Nautical Research Journal, Vol. 1, No. 27 (June 1993).

Red Pirogue

Lewis left Pittsburgh on 31 August 1803, with a crew of eleven hands, seven of whom were soldiers, plus “three young men on trial they having proposed to go with me throughout the voyage.” (Among the fourteen may have been George Shannon and John Colter.) He had hired a pilot named T. Moore, who was paid $70 to go as far as the Falls of the Ohio at Louisville.[5]Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents 1783–1854, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:125 and note. Four days out of Pittsburgh, on 4 September 1803, Lewis wrote that “the Perogue was loaded as his been my practice since I left Pittsburgh, in order as much as posseble to lighten the boat [barge].” The description of the use of his “Perogue” suggests that it was a large open boat with a capacity in excess of what might be carried in a dugout canoe. His next words confirm that assertion:

The man who conducted her called as in distress about an hour after we had got under way, we came too and waited her coming up found she had sprung a leek and had nearly filled; this accedent was truly distressing, as her load consisting of articles of hard-ware, intended as presents to the Indians got wet and I fear are much damaged.

He put up with it for another few days, and when he arrived in son of Robert Patterson, the mathematician from whom Lewis had recently received training in celestial navigation, (now West) Virginia on the eighth, he “purchased a perogue and hired a man to work her.” The next day he reported that the previous night he had “had my perogues covered with oil-cloth, but the rain came down in such torrents that I found it necessary to have them bailed out freequently in the course of the night.” It is clear that he now had two auxiliary boats, but whether they were long narrow dugouts or larger built-up boats is not clear. By “work her,” in the first instance, did he mean “paddled,” or “piloted”?[6]In a nautical context, the Oxford English Dictionary Online defines the verb work as meaning “to direct the movement of (a ship) by management of the sails and rudder,” or “to move … Continue reading Was this one a canoe or a boat made of planks? He hardly had enough men to crew the barge and two pirogues. Did he abandon the pirogue he left Pittsburgh with? Since the purpose of the extra watercraft was to lighten the barge and thereby facilitate its progress down the shallow late-summer Ohio, logic suggests that they were larger than dugout canoes, and would have required more than a one-man crew. It is possible that this is the boat which became known, after receiving a fresh coat of paint, as the red pirogue or, alternatively, the “French pirogue,” because it was manned by nine of the French Canadian engagés who were hired at St. Charles to assist the Corps as far as the Mandan villages (see The St. Charles Boatmen).

When the expedition reached the mouth of the Marias River on 10 June 1805, the captains chose to leave the red pirogue there and proceed with the smaller white one. While seven of the men dug a cache, and a few others set up a rope walk to make a new tow-rope for the white pirogue, the rest of the party was busy beaching and hiding the other boat. As Lewis explained it, “we drew up the red perogue into the middle of a small Island at the entrance of Maria’s river, and . . . made her fast to the trees to prevent the high floods from carrying her off put my brand (see Lewis’s Branding Iron) on several trees standing near her”–to keep Indians from disturbing her, according to Sergeant Ordway–”and covered her with brush to shelter her from the effects of the sun.” However, en route home on 28 July 1806, Lewis and his detachment, paddling the canoes and rowing the white pirogue down the Missouri from the Falls, stopped at the mouth of the Marias to retrieve the property they had cached there, and re-launch the red pirogue. Unfortunately, they found the boat “so much decayed that it was impossible with the means we had to repare her,” so they hastily salvaged all the nails “and other ironwork’s” they could, and headed downriver. Was she really suffering from rot? Or had the spring flood, and the debris it carried, stove in her hull?

On the basis of selected 18th-century documentation, Richard Boss concluded that the red pirogue may have had a length of 41 feet 7 inches, a beam of 9 feet 4 inches, and a capacity of 9 tons. Boss speculated that both pirogues were flat-bottomed, with sharp-angled chines.[7]Chines are the lines where the sides and bottom of a craft meet. The chines may be sharp, or more or less rounded. That would made them akin to the common bateau, or the famed Schenectady boat that was frequently used for freighting on New England rivers between 1790 and 1825–although neither captain used that name in reference to their own pirogues. Clark, in his journal entry for 20 September 1806, related that at least two of five traders’ boats they saw that day were from Canada. He noted that they were “in the batteaux form, . . .

their length about 30 feet and the width 8 feet & pointed bow & Stern, flat bottom and rowing Six ores only the Skeneckeity form. those Bottoms are prepared for the navigation of this river, I beleive them to be the best Calculated for the navigation of this river of any which I have Seen. . . . they are wide and flat not Subject to the dangers of the roleing Sands, which larger boats are on this river.

None of the journalists mentioned any specific differences between the Canadian traders’ boats and the expedition’s pirogues.[8]“The Schenectady Boat” (New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, NYS Division of Military and Naval Affairs. http://www.historicstockade.com/historycenter/hc_boat.htm … Continue reading

Figure 3

Clark’s Sketch of the White Pirogue

To see labels, point to the image.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

This drawing[9]From document 10 in Clark’s Field Notes; Moulton, ed., Journals, 2:196. Image, courtesy of the Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; Bibliographic … Continue reading provides the only visual clue left us as to any aspect of either one of the pirogues. The arrangement of six rowlocks tells us that it depicts the white, or “Soldiers” pirogue as Clark described it on 13 May 1804. The figures 4 and 6 presumably indicate the number of “tuns” of cargo that could be carried in each compartment; the other two symbols are of uncertain meaning. If “tuns” is a Clark-ism for tons, then eight tons, or 16,000 pounds, would be its carrying capacity—the burden, or burthen as it was commonly spelled—with a potential maximum load of 14 tons, or 28,000 pounds. Coincidentally, Clark’s “misspelling” was also a valid seaman’s term denoting a flexible unit of volume equal either to the space occupied by a cask or barrel with a capacity of about 250 gallons—perhaps 40 cubic feet–or else the volume of 2000 lbs. of water—about 32 cubic feet.[10]Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “tun.” William Henry Smyth and Edward Belcher, The Sailor’s Word-Book: An Alphabetical Digest of Nautical Terms (London: Blackie and Son, … Continue reading On one occasion Lewis implied the solution to this little conundrum when he estimated that the upper Osage River would be navigable by “perogues of eight or ten tons burthen,” implying that that was the standard size. From that we can infer that Clark had in mind tons rather than tuns.[11]In his description of the Osage River, Lewis relates that it is “navigable 120 leagues for boats and perogues of eight or ten tons burthen, during the fall and spring seasons.” Moulton, … Continue reading

The end at right is the stern, with the rudder outside of it and the tiller inside. The line looping upward from it might represent a rope that would have been used when cordelling (towing) to control the distance of the stern from the riverbank. Another rope, not shown, would have been attached on the bow (left) at or below the waterline, to cordell the pirogue upstream and around snags or other obstacles in the shallows.

White Pirogue

Early in July of 1803, a scant month before Lewis would finally leave Pittsburgh and head down the Ohio on his new barge, secretary of War Henry Dearborn issued an order to Captains Russell Bissell and Amos Stoddard at Fort Kaskaskia in the Illinois Country, southeast of St. Louis:

You will be pleased to furnish one Sergeant & Eight good Men who understanding rowing a boat to go with Capt. Lewis as far up the River as they can go & return with certainty before the Ice will obstruct the passage of the river. They should be furnished with the best boat at the Post & take in provisions for Capt. Lewis’s party & themselves. If an officer should be inclined to go with the boat, he should be prefered. It would be desirable that the party should go voluntarily, if a sufficient number of suitable men should offer.[12]Henry Dearborn to Russell Bissell and Amos Stoddard, 2 July 1803. Jackson, Letters, 1:103-04. Bissell was in charge of the fort; Captain Stoddard commanded a company of artillerists. Fort Kaskaskia … Continue reading

This was undoubtedly the boat the captains painted white so that it could easily be distinguished at a distance from the other one, which they painted red. It may have been built-up of tulip poplar planks, which was the preferred material for boat-building in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys.[13]Liriodendron tulipifera L.; so-called from the shape of its flower. Clark wrote in his “Remarks” for 23 February 1805 at Fort Mandan, that the men “got the poplar perogue out of the ice,” which may be interpreted as confirmation that the white pirogue was the one acquired at Fort Kaskaskia.

Nautical historian Richard Boss, who built the scale models of the two pirogues pictured here (Figures 2 and 3) concluded that all available evidence suggests that the expedition’s white pirogue may have been 39 feet long, with a beam of 8 feet 8 inches.[14]Boss, 80. That would mean that its optimum capacity would have been 8 tons of cargo, plus six oarsmen, a helmsman, and a bowman (the first syllable rhymes with now).

Fully loaded, the white pirogue would have drawn about 20 inches of water, leaving 19 inches of freeboard–the distance between the water and the lowest point on the gunwales (pronounced gunnels). Each of the five-foot cargo compartments could have been loaded one foot higher than the gunwales (Figure 4). On 6 May 1804, Lewis, who was still in St. Louis, wrote to Clark requesting that he send the “small perogue” down to St. Louis to have “way-strips” added atop her gunwales. Way-strips, better known as wash-strakes, helped to prevent spray from splashing into the boat. Clark received the letter on the seventh via John Colter, and immediately dispatched Sgt. Ordway to St. Louis with “a perogue,” presumably the white one. Richard Boss included wash-strakes on his model of the white pirogue, reinforced by wooden brackets (not visible) called poppets, which would support the rowlocks–the notches serving as thole-pins. Each oar is secured to the thole-pin by means of a grommet, which is a triple ring made of a single strand of rope wrapped around the loom where it rests in the oar-lock, looped with a twist over the thole-pin, then back around the loom and tied off. (See the illustration and description in The Barge.)

The white perogue served as the expedition’s flagship from Fort Mandan to the Falls of the Missouri. The naval pennant signifying the captains’ presence on board flew from a pole attached to the tip of the sprit, the single spar that gave the spritsail its name. Both the spritsail and the square mainsail were “loose-footed,” that is, without booms or spars at their bottoms. They were controlled by ropes either tied to cleats, or hand-held by a crewman who could simply let go of them if a strong wind pressed the boat too much.

The awning at the stern sheltered one or both of the captains from sun and rain and, on the day in early June of 1805 when Clark recorded that Sacagawea had fallen ill, they made room for her in its shade. “I move her to the back part of our Covered part of the Perogue which is Cool,” he wrote, “her own situation being a verry hot one in the bottom of the Perogue exposed to the Sun.” On the return journey down the Missouri in 1806, Lewis replaced the torn and useless canvas awning with stitched-together elk skins.

Four of the white pirogue’s six oars rest in their rowlocks in the cramped bow. They are single-banked, which means that one oarsman would have been seated on each thwart (bench) facing astern (with his back to the camera). The thwarts are close together, and the handles of the oars overlap one another, so the oarsmen would have to carefully coordinate their strokes. They could take simultaneous strokes, but they would have to alternate their pulling and returning motions. That is, when the blade is deep in the water, the oarsman’s hands are high in the air, and on the return stroke, when the blade is out of the water, his hands are low. So, as long as their strokes were timed so that hands were high on one side, while low on the other, the oar handles, or looms, would oppose each other in continuous circles.

Crews

In a letter to Lewis (who was in St. Louis) on 13 May 1804, Clark had written from Camp Dubois that their flotilla would depart the next day in the “Boat of 22 oars, a large Perogue of 7 oares” manned by 8 Frenchmen, and “a Second Perogue of 6 oars Complete with Sails[15]This tells us that the white pirogue had more than one sail. &c. &c.” (the so-called white pirogue) manned by soldiers. The captains revealed more details in their Detachment Orders of 26 May 1804, which suggest that one of the qualifications of the sergeants was competency in all aspects of handling boats under oar and sail. In professional terms, within the limits of river navigation, they were “able seaman,” although they were never called that. Aside from the captains, the only other men with like qualifications were Pierre Cruzatte, François Labiche, and perhaps George Drouillard.

From Camp Dubois to Fort Mandan the white pirogue was known as the “Soldiers” boat because it was under the command of Corporal Richard Warfington, and crewed by his five soldiers, Privates John Boley, John Dame, Robert Frazer, Ebenezer Tuttle, and Isaac White—plus John Robinson, perhaps—all of whom would help man the barge on its return trip to St. Louis from Fort Mandan in the spring of 1805. Boley, Dame, Tuttle and White were from Fort Kaskaskia

The captains’ original plan, first mentioned in Clark’s Field Notes on 4 July 1804, was to send the white pirogue back to St. Louis from the mouth of the Platte River with reports to be forwarded to President Jefferson. For the next few weeks they kept that in mind, and continued to prepare for it by drawing maps and writing dispatches (see journal entries for 24 July 1804 and 12 August 1804). Evidently they had postponed that plan by the time they arrived at the Platte on 21 July 1804, for they proceeded on from there without mentioning it. On 16 September 1804, however, because increasing numbers of sandbars were impeding the progress of the barge, and they were losing time. For that reason, wrote Clark, they decided to move some of the barge’s cargo to the white pirogue “& detain the Soldiers untill Spring & Send them from our winter quarters.” That was a practical expedient, for the barge could easily return to St. Louis on the spring freshet with the large quantity of mineralogical, botanical and other specimens, and “Donations” of gifts from Indians, to President Jefferson (see Jefferson’s Indian Hall) and Benjamin Smith Barton, which might not have fit into the white pirogue.

Poling

Setting poles are slung from the gunwales. Lewis reported that the stem of the “narrow leaf willow” (Salix longifolia) was ideally suited for this purpose. “It is seldom seen larger than a mans arm,” he wrote, “and scarcely [ever] rises higher than 25 feet. the wood is white light and tough, and is generally used by the watermen for setting poles in preference to anything else.” On one occasion, according to Sergeant Gass, they came upon “an old Indian camp, where we found some of their dog-poles, which answer for setting poles.”[16]Moulton, Journals, 2:455 (Fort Mandan Miscellany, Part 3: Botanical Collections). Gass explained further: “The reason they are called dog-poles, is because the Indians fasten their dogs to … Continue reading

By the summer of 1805, most of the iron tips of their original poles had been lost, and Lewis noticed, on 23 July 1804, that the riverbed stones were so smooth that “the points of their poles sliped in such manner that it increased the labour of navigating the canoes very considerably.” Fortunately, he had brought along a “parsel of giggs” for spearing fish or frogs, and “made the men each atatch one of these to the lower ends of their poles with strong wire, which answered the desired purpose.”

Sailing

During the nearly 600 days when the Corps of Discovery was on one river or another, they were under sail a little more than one-tenth of the time. The job of rowing, poling, cordelling, or warping a boat up a river, day after day, required some training and experience. Landlubbers had to be “quick studies.” No matter how small the crew, each member had to learn to be part of a team that was different from a squad of army riflemen. They might casually admire the scenery or the wildlife, or shake off mosquitoes and gnats, but their minds had to be focused primarily on the job. Their days would have been measured by a more or less continuous flow of commands from the bowman, who barked orders to the stroke-oar–the aftermost oarsman in the boat, from whom the others took their visual cues for pace, length and depth of stroke. The stroke-oar would have been the seventh in the red pirogue, and the aftermost starboard oar in the white pirogue.

Ascending a river, the crew’s reactions had to be swift and sure; lapses could cost precious headway in the blink of an eye. Descending a river was no less demanding. The bowman had keep his boat at least slightly ahead of the current in order to maintain control of it if a hazard is encountered. A boat drifting freely on the water is at the current’s mercy, and since flowing water is essentially chaotic, with many forces producing random flows near the surface, a boat in the river’s grasp will be forced to travel wherever the water takes it. Failure to avoid a collision with a raft of logs could result in capsizing the boat and sweeping the crew beneath the logs. Every pilot and helmsman, and every man who handled one or both of the “braces” (ropes attached to each corner of the square sail), had to pay close attention to the alignment of his boat relative to the direction and force of the wind, a responsibility that was complicated by tortuous riverine courses and sometimes “flawy” (gusty) prairie winds—not to mention the hazards of rocks, sandbars, sawyers, snags, and falling banks.

The Corps of Discovery was not unique in confronting these challenges. The Missouri and the Columbia, like the Ohio and the Mississippi, were big rivers, and every party that used those highways had to learn the same skills, or else face certain disaster.

Armaments

The posts in the bows of both pirogues would each have supported a blunderbuss, a short-range defensive weapon with a large bore and a wide mouth. Those firelocks were often used at sea for repelling boarders, and the captains were prepared to use them that way if necessary. When the Lakota Sioux abruptly turned belligerent on 24 September 1804, Lewis ordered all his men to arms and, according to Sergeant Ordway, commanded that the large swivel cannon on the barge be loaded with sixteen musket balls, and “the 2 other Swivels loaded well with Buck Shot, Each of them manned.” Fortunately, open conflict was averted, and no similar situations arose thereafter. The blunderbusses, with their characteristic smoke and noise, served well for signaling, and for celebrations such as their return to St. Charles on 21 September 1806, when they saluted the villagers at St. Charles with three rounds from the “blunderbuts.”

Accidents

The design or performance characteristics that made the white pirogue more “steady and safe” than the red one, according to the captains, are not known to us. But accidents could happen even to the best of boats. In his journal entry for 13 April 1805, one week after departing from Fort Mandan, Lewis described the rigging of the white pirogue (which Richard Boss re-created on his model, above), and explained what happened when the wind suddenly took control.

the wind was in our favour after 9 A. M. and continued favourable untill . . . 3 P. M. we therefore hoisted both the sails in the White Perogue, consisting of a small squar sail, and spritsail[17]The spritsail is a fore-and-aft sail with its forward edge attached to the mast and supported by a spar called a sprit. When the boat is steered close to the wind’s direction, the sail can lose … Continue reading, which carried her at a pretty good gate [gait, or rate], untill about 2 in the afternoon when a suddon squall of wind struck us and turned the perogue so much on the side as to allarm Sharbono who was steering at the time, in this state of alarm he threw the perogue with her side to the wind, when the spritsail gibing[18]The term jibe (rhymes with tribe) is the sudden swinging of a fore-and-aft sail from one side to the other when sailing with the wind more or less over the stern. Jibing is caused (intentionally or … Continue reading was as near overseting the perogue as it was possible . . . . the wind however abating for an instant I ordered Drewyer to the helm and the sails to be taken in, which was instant executed.

On 21 August 1804, a little more than three months after the expedition began, Clark recorded that the company “Set out verry early . . . under a Gentle Breeze from the S. E,” but within an hour, while still passing a sandy island on their second course of the day, conditions suddenly worsened: “Wind blow’s hard.” Ordway termed it “a hard Breeze,” adding that for some distance “the wind blew so hard that we were oblidged to take a reefe[19]To reef a sail is to reduce its size as the wind increases. Smythe, The Sailor’s Word-Book, s.v. “reef.” in our Sail.” Meanwhile, “the white pearogue could hardly Sail for want of Ballass,” so they moved several kegs of pork, “&.C” from the barge to the smaller vessel. Each keg could have weighed as much as ninety pounds.[20]At Camp Dubois, Clark indicated on 16 April 1804, that a keg of pork weighed a little over seventy pounds, but his inventory dated 14 May 1804 indicates it would have been ninety pounds. Newton H. … Continue reading

The rudder irons, or pivots on which the rudder was hung, were firmly attached to the stern-post. They broke when the pirogue hit a snag on 5 May 1805, but were promptly repaired by the expedition’s blacksmith, John Shields. A naval pennant (See The Expedition’s Flags) bearing the colors of the United States flew from the highest point on the boat–on the tip of the yard of the lateen sail on the white pirogue, and atop the mainmast of the red pirogue (see below).

The white pirogue’s precious cargo included instruments, papers, medicine, and Indian presents, plus three non-swimmers—including Charbonneau—and Sacagawea with her three-month old baby boy. Altogether, the threat that all might be lost filled Lewis with dread. However, he wrote, “we fortunately escaped and pursued [proceeded] under the square sail, which shortly after the accident I directed to be again hoisted.”

Poor Charbonneau was a slow learner. A month later, on 14 May 1805, he was again at the tiller of the same craft, temporarily in place of George Drouillard, and he made the same mistake again when “a sudon squawl of wind struck her obliquely, and turned [heeled] her considerably.” The consequences of that event are detailed in Charbonneau’s Prayer.

It all turned out alright, but Fate seemed to have the white pirogue in her sights. Fifteen days later, on the night of the 28th, a large bull bison crossing the river in the middle of the night climbed over the white pirogue that was beached near camp, severely damaging York‘s rifle and one of the blunderbusses aboard. Lewis felt “well content, happey indeed,” that they had suffered no greater injury, considering that the animal had narrowly missed treading on the heads of some of the soldiers sleeping on the ground nearby. Nevertheless, he concluded, “it appears that the white perogue, which contains our most valuable stores, is attended by some evil gennii.”[21]The word genii, the plural of genius, was used in Roman mythology in the sense of a superior guardian spirit, either good or bad, of a person, place, or situation. American Heritage Dictionary of the … Continue reading

Evidence of that mounted steadily. Only two days later, when the white perogue’s crew was cordelling her with the last remaining hemp tow-rope—”the safest and most expeditious mode of traveling,” Lewis had declared—it broke. The boat swung in the current “and but slightly touched a rock, yet was very near overseting.” This time Charbonneau was not at fault, but Lewis was nonetheless perturbed over the incident: “I fear her evil gennii will play so many pranks with her,” he sighed, “that she will go to the bottomm some of those days.”

History proved his fears were unwarranted. The white pirogue survived the winter of 1805-06 hidden on shore opposite the portage camp below the Falls of the Missouri, and led the Corps’ flotilla of dugouts triumphantly back to St. Louis.

Pirogue or Canoe?

In the days of Lewis and Clark the noun pirogue, clad in many different spellings and shades of meaning, was aimlessly adrift in the sea of names. It was absent from Noah Webster’s Compendious Dictionary (published in 1806 while the expedition was still under way), being omitted, one supposes, because Webster didn’t feel it had yet earned a legitimate place in American colloquial speech. Only twenty-two years later, however, he listed it in his American Dictionary of the English Language, since by then it was, he flatly asserted, “in modern usage in America,” and could be defined simply as “a narrow ferry-boat carrying two masts and a lee board.”[22]Lee-boards are “wooden wings or strong frames of plank affixed to the sides of flat-bottomed vessels . . . traversing on a stout bolt, [which], by being let down into the water, when the vessel … Continue reading Another generation later the original meaning of pirogue was reasserted: “A canoe formed from the trunk of a large tree, generally cedar or balsa wood. It was the native vessel that the Spaniards found along the rivers of Central America, and on the west coasts of South America,” and in North America was sometimes called a dug-boat or dugout canoe.[23]Smyth and Belcher, 407, s.v. pirogue.

Meriwether Lewis used perogue in both senses–to denote either a large, open, built-up boat made from planks and frames, which was powered by oars; or a long, narrow canoe that was “dug out,” or carved, from a tree trunk, and was propelled with paddles.[24]The white pirogue’s oars may have been eighteen feet long, according to historian Richard Boss. The inboard portion of each oar, called the loom, rested on the gunwale in a rowlock, pivoting on … Continue reading Given the happy coincidence of wind direction and river azimuth, both types were sometimes powered by sails. Apparently, his choice of terms was capricious, and it began with his departure from Pittsburgh on 31 August 1803, with one “perogue” in addition to the barge. Five days later he explained the purpose of the extra boat, in the context of a misfortune:

the Perogue was loaded as his been my practice since I left Pittsburgh, in order as much as posseble to lighten the boat, the [man] who conducted her called as in distress about an hour after we had got underway, we came too and waited her coming up found she had sprung a leek and had nearly filled; this accedent was truly distressing, as her load consisting of articles of hard-ware,[25]Possibly including the two cast-iron corn mills that Jefferson had urged Lewis to take along, which would have been seriously damaged if they were allowed to rust. intended as presents to the Indians got wet and I fear are much damaged.

His description clearly suggests that the “perogue” was a rather large open boat with a considerable capacity. Then at Georgetown, Pennsylvania, on the same day, he

purchased a canoe compleat with two paddles and two poles for which I gave 11$, found that my new purchase leaked so much that she was unsafe without some repairs.

It may have been a dugout canoe carved from a cottonwood or tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) bole of unknown length, or perhaps the trunk of a chestnut or white pine tree, perhaps 15 or 20 feet long and three or four feet in diameter.[26]Chapelle, 36-37. Early that evening he set some of his hands to repairing “the canoes”–evidently referring to both the “pirogue” and the “canoe.” At Wheeling on the 8th of September he wrote to President Jefferson: “I have been compelled to purchase a perogue at this place in order to transport the baggage which was sent by land from Pittsburgh, and also to lighten the boat [i.e., the barge] as much as possible.”[27]Jackson, Letters, 1:122. He also hired a man to “work” her. Again it seems he is referring to a large open boat; he may have abandoned the first pirogue at Wheeling in favor of a new one. The confusion was compounded on 18 November 1803 when, while the rest of the crew laid by at the mouth of the Ohio Lewis “set out . . . with a canoe and eight men in company with Captain Clark” to take a short trip down the Mississippi to visit the site of “Oald Fort Jefferson.” It seems likely they really were in a pirogue, with six or seven of the eight men at the oars; that would have been the most efficient conveyance for stemming the Mississippi’s brisk current on the return trip, and nine men in a dugout canoe would have been uncomfortable to say the least.

When Lewis wasn’t keeping his journal, Clark’s use of “perogue” and occasional orthographic variations was consistent. However, at Fort Mandan in the spring of 1805, Lewis consistently referred to the boats the men were carving from cottonwood logs as “perogues”—until 7 April 1805, that is, when the Corps left the fort on the next leg of their journey, and he recorded that their vessels consisted of “six small canoes, and two large perogues,” the latter term meaning the two built-up rowboats. But after reaching the headwaters of the Missouri and making the laborious crossing of the Bitterroot Range in September 1805, they paused among the friendly Nez Perce and began carving six dugouts to convey them and their baggage down to the sea. In a famous letter to an unknown correspondent, Lewis reverted to the old meaning of perogue, writing in his journal that the men soon got to work and carved “four large Pirogues & a small Canoe.”[28]Jackson, Letters, 1:339. By 1810, a copy of that long document, titled “Sketch of Captn. Lewis’s Voyage to the Pacific Ocean by the Missesourii & Columbia Rivers from the States of … Continue reading

The following spring, however, as they made their way back up the Columbia from Fort Clatsop, Lewis returned to his old habit, referring to the Indians’ boats as canoes, and to their own battered ponderosa pine dugouts as pirogues. (They had recently “taken” one small canoe from the Clatsops, and soon purchased another.) On 2 April 1806, he said that he intended to trade their old dugouts for some of the natives’ light, sleek canoes, or else purchase them outright with elk skins. On the twelfth, the raging Cascades of the Columbia snatched one of their own dugouts out of their hands and carried it swiftly downriver. The mishap worried Lewis greatly. They were desperately short of trade goods, and, he worried, “the loss of this perogue [i.e., dugout canoe] will I fear compell us to purchase one or more canoes of the indians at an extravegant price.” Another six days later the high, rough and rapid water compelled the men to unload the “perogues and canoes” and manhandle their baggage over a short portage of seventy paces, then wrestle their “five small canoes” up the rapids using cords and setting poles. The two “perogues”—the ponderosa pine dugouts they had hurriedly made the previous fall on the Clearwater River—they “could take no further and therefore cut them up for fuel.”

Sergeant Ordway used pirogue in a similarly ambiguous way. In early November 1804, he stated: “Several more of our french hands is discharged and one makeing a pearogue in order to descend the Missourie.” Undoubtedly he meant a cottonwood dugout canoe. One day in February, 1805, at Fort Mandan Ordway used “perogue” both ways in the same journal entry: They moved “the 2 perogues along the N. Side of the line of huts”—where they would be sheltered from direct sunlight—so as to keep the sun from drying them too quickly and thereby cracking them. Those would have been the boats they referred to otherwise as the red and white pirogues. The next sentence, however, clearly refers to dugout canoes: “16 men Got their tools in order to make 4 perogues 4 men destined [assigned] to make each perogue.”

Complicating the confusion, the anonymous scribe who later paraphrased Private Whitehouse’s journal changed his author’s preferred “canoe” to pettyauger, one of numerous variants of the Spanish piragua through perriago and perryauger, all denoting either a single canoe hollowed from a tree trunk, or two such canoes fastened together side-by-side.[29]Oxford English Dictionary Online, retrieved 17 August 2008. Pettyauger was common on the southern U.S. Atlantic Coast and around the mouth of the Mississippi. Dictionary of American Regional English, … Continue reading In the eighteenth century, the name “periagua” was often applied to a large dugout canoe fitted with a sail.[30]Chapelle, 18. At his Yellowstone River canoe camp on 20-24 July 1806, Clark devised something close to one of the latter by tying his two new, narrow 28-foot dugouts together for stability.[31]Each was “about 16 or 18 inches deep and from 16 to 24 inches wide.” Moulton, Journals, 8:209. After they shipped water while passing through a riffle, he had buffalo skin tacked over the adjacent gunwales to keep water from “flacking in.”

Naming people, places and things is a human impulse. The Enlightenment institutionalized that impulse, and made it the ultimate purpose of an explorer’s job–to observe (“discover”), describe, and name. That’s basically what the expedition’s journals contain–observations, descriptions, and names. But some names refuse to stand still for the lexicographer. Take pirogue, for instance. The Fourth Edition (2000) of the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language omits it, but lists its Spanish-Caribbean antecedent, piragua, with two definitions: First, “A canoe made by hollowing out a tree trunk; a dugout.” and second, “A flat bottom sailing boat with two masts.” By the spring of 2009, however, the most recent descendant of Webster’s 1806 Compendious Dictionary had reverted to the definition of pirogue that coincided with Lewis’s: “a boat made by hollowing out a large log.”[32]Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/pirogue (retrieved 29 July 2009).

Notes

| ↑1 | John W. Fisher, “The Pirogue,” Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly 48, no. 3 (Fall 2012): 1–13. See also Mark W. Jordan, “Watercraft of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Comprehensive Inventory,” We Proceeded On 28, no. 2 (May 2022), p. 25–27. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The classic study of boats that were used in America between Colonial times and the end of the nineteenth century, in which more than sixty distinct types and designs are described and illustrated, is Howard I. Chapelle’s American Small Sailing Craft: Their Design, Development, and Construction (New York: Norton, 1951), esp. pp. 17-19. Chapelle did not specifically mention the pirogue as Clark used the term, but in his discussion of “The Periagua,” which he defines as a large dugout canoe fitted to sail, he acknowledges that during the last decade of the eighteenth century the Spanish term had begun to be applied to larger, more built-up boats with masts and sails. Constantine Rafinesque, whom we have met several times elsewhere in Discovering Lewis & Clark, wrote in an article about the Ohio River that besides steamboats (which in 1820 had recently begun to ply the major rivers), the Ohio was navigated by “Barges, Keel boats, Schooner barges, Rowing boats, Flat boats or Arks, Skiffs, Pirogues, Rafts, &c. of which many thousand annually descend the stream. Those which ascend it again amount annually to many hundred.” “Description of the River Ohio,” The Western Review and Miscellaneous Magazine,” Vol. 1 No. 6 (January 1820), 362. Six years later the Reverend Timothy Flint described the bewildering variety of watercraft on American rivers, including a description of the pirogue: “There are what the people call ‘covered sleds,’ or ferry-flats, and Allegany-skiffs, carrying from eight to twelve tons. In another place are pirogues of from two to four tons burthen, hollowed sometimes from one prodigious tree, or from the trunks of two trees united, and a plank rim fitted to the upper part. There are common skiffs, and other small craft, named, from the manner of making them, ‘dug-outs,’ and canoes hollowed from smaller trees. These boats are in great numbers, and these names are specific, and clearly define the boats to which they belong. But besides these, in this land of freedom and invention, with a little aid perhaps, from the influence of the moon, there are monstrous anomalies, reducible to no specific class of boats, and only illustrating the whimsical archetypes of things that have previously existed in the brain of inventive men, who reject the slavery of being obliged to build in any received form. You can scarcely imagine an abstract form in which a boat can be built, that in some part of the Ohio or Mississippi you will not see, actually in motion.” Timothy Flint, Recollections of the Last Ten Years, passed in occasional residences and journeyings in the Valley of the Mississippi,from Pittsburg and the Missouri to the Gulf of Mexico (Boston: Cummings, Hilliard, and Company, 1826), 14. |

| ↑3 | In northern urban America the pronunciation is pi-rogue (with a long o in the accented second syllable, and a hard g as in go pronounced backwards). Down in Mississippi and Louisiana the 17th century French word (derived in the preceding century from the Spanish piragua) is pronounced as in French, pee-row–the way Charley Pride sang it in his 1970 recording of “Pirogue Joe.” |

| ↑4 | Richard Boss, “Keelboat, Pirogue, and Canoe: Vessels Used by the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery,” Nautical Research Journal, Vol. 1, No. 27 (June 1993). |

| ↑5 | Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents 1783–1854, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:125 and note. |

| ↑6 | In a nautical context, the Oxford English Dictionary Online defines the verb work as meaning “to direct the movement of (a ship) by management of the sails and rudder,” or “to move and direct (a boat), as with oars,” and cites Sergeant Gass, writing on 30 March 1806, of the Indians on Sauvie Island: “The natives of this country ought to have the credit of making the finest canoes, perhaps in the world, both as to service and beauty; and are no less expert in working them when made.” |

| ↑7 | Chines are the lines where the sides and bottom of a craft meet. The chines may be sharp, or more or less rounded. |

| ↑8 | “The Schenectady Boat” (New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, NYS Division of Military and Naval Affairs. http://www.historicstockade.com/historycenter/hc_boat.htm (retrieved 7 July 2009). The denotation of the term bateau (and other spellings of the French word for boat), is similarly ambiguous. Here, Clark implies that it resembled the Schenectady boat, but that is not quite correct. Ordway, in his very first journal entry (14 May 1804), went so far as to refer to the barge as “the Batteaux.” See Joseph F. Meany, Jr., “Bateaux and ‘Battoe Men’: An American Colonial Response to the Problem of Logistics in Mountain Warfare,” ibid., http://www.dmna.state.ny.us/historic/articles/bateau.htm (retrieved 7 July 2009). |

| ↑9 | From document 10 in Clark’s Field Notes; Moulton, ed., Journals, 2:196. Image, courtesy of the Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; Bibliographic Record Numbers 2003022, 1013092. |

| ↑10 | Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “tun.” William Henry Smyth and Edward Belcher, The Sailor’s Word-Book: An Alphabetical Digest of Nautical Terms (London: Blackie and Son, 1867), 686. |

| ↑11 | In his description of the Osage River, Lewis relates that it is “navigable 120 leagues for boats and perogues of eight or ten tons burthen, during the fall and spring seasons.” Moulton, Journals, 3:340. League was an unofficial but common unit of measurement at that time. On land, a league was approximately three miles, or the distance an average person could walk in one hour. A nautical league was equal to 3041 fathoms, or 18,246 feet—a little over 3.45 land miles. It doesn’t really matter which unit Lewis had in mind, since it was merely an estimate based on hearsay. He didn’t explore the Osage to its source. Coincidentally, its official length today is said to be 360 miles, or exactly 120 land-leagues. |

| ↑12 | Henry Dearborn to Russell Bissell and Amos Stoddard, 2 July 1803. Jackson, Letters, 1:103-04. Bissell was in charge of the fort; Captain Stoddard commanded a company of artillerists. Fort Kaskaskia was located on the east bank of the Mississippi in the Illinois Country, about fifty river-miles southeast of St. Louis. After the Territory was officially turned over to the U.S., Stoddard was named temporary commandant of U.S. forces in Upper Louisiana. Jackson, Letters, 1:180. |

| ↑13 | Liriodendron tulipifera L.; so-called from the shape of its flower. |

| ↑14 | Boss, 80. |

| ↑15 | This tells us that the white pirogue had more than one sail. |

| ↑16 | Moulton, Journals, 2:455 (Fort Mandan Miscellany, Part 3: Botanical Collections). Gass explained further: “The reason they are called dog-poles, is because the Indians fasten their dogs to them, and make them draw them from one camp to another loaded with skins and other articles.” The dog travois was the customary freight carrier for many Indian tribes before the introduction of the horse. Ibid., 10:42 and note 5. |

| ↑17 | The spritsail is a fore-and-aft sail with its forward edge attached to the mast and supported by a spar called a sprit. When the boat is steered close to the wind’s direction, the sail can lose its aerodynamic tension, and flutter, or luff, leaving the boat out of control. |

| ↑18 | The term jibe (rhymes with tribe) is the sudden swinging of a fore-and-aft sail from one side to the other when sailing with the wind more or less over the stern. Jibing is caused (intentionally or accidentally) by the steersman, or by a shift in the wind direction or, as in this instance, both. It may result not only in loss of control of the vessel but also damage to spars and rigging. |

| ↑19 | To reef a sail is to reduce its size as the wind increases. Smythe, The Sailor’s Word-Book, s.v. “reef.” |

| ↑20 | At Camp Dubois, Clark indicated on 16 April 1804, that a keg of pork weighed a little over seventy pounds, but his inventory dated 14 May 1804 indicates it would have been ninety pounds. Newton H. Winchell and others, The History of the Upper Mississippi Valley (Minneapolis: Minnesota Historical Co., 1881), 185, says a keg of pork normally weighed about eighty pounds. |

| ↑21 | The word genii, the plural of genius, was used in Roman mythology in the sense of a superior guardian spirit, either good or bad, of a person, place, or situation. American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Third Edition. |

| ↑22 | Lee-boards are “wooden wings or strong frames of plank affixed to the sides of flat-bottomed vessels . . . traversing on a stout bolt, [which], by being let down into the water, when the vessel is close-hauled [heading nearly straight into the wind], decrease her drifting to leeward.” The lee side of a vessel is the side opposite to that from which the wind is blowing, called the weather side. Smyth and Belcher, s.v. lee-boards. |

| ↑23 | Smyth and Belcher, 407, s.v. pirogue. |

| ↑24 | The white pirogue’s oars may have been eighteen feet long, according to historian Richard Boss. The inboard portion of each oar, called the loom, rested on the gunwale in a rowlock, pivoting on a thole-pin to which it was attached with a rope grommet. The oarsmen were seated on benches called thwarts, which also served to stabilize the lateral frame of the craft. Whereas the barge, with its 8’4″ beam, could accommodate double-banked oars, meaning two oarsmen were seated on each thwart, the narrower pirogues were single-banked, with each oarsmen seated on a separate thwart. Paddles are shorter than oars, usually a little less than the canoeist’s height; the Corps’ canoeists probably kneeled in the dugouts in order to keep their craft’s center of gravity low. Their strokes would have been deeper than those of the pirogues’ rowers. When circumstances required, the paddlers could stand and propel the canoe with iron-tipped poles that would have been at least ten feet or as much as 18 feet long. |

| ↑25 | Possibly including the two cast-iron corn mills that Jefferson had urged Lewis to take along, which would have been seriously damaged if they were allowed to rust. |

| ↑26 | Chapelle, 36-37. |

| ↑27 | Jackson, Letters, 1:122. |

| ↑28 | Jackson, Letters, 1:339. By 1810, a copy of that long document, titled “Sketch of Captn. Lewis’s Voyage to the Pacific Ocean by the Missesourii & Columbia Rivers from the States of America,” was received by the Canadian trader and explorer David Thompson. |

| ↑29 | Oxford English Dictionary Online, retrieved 17 August 2008. Pettyauger was common on the southern U.S. Atlantic Coast and around the mouth of the Mississippi. Dictionary of American Regional English, s.v. “pettyauger.” |

| ↑30 | Chapelle, 18. |

| ↑31 | Each was “about 16 or 18 inches deep and from 16 to 24 inches wide.” Moulton, Journals, 8:209. |

| ↑32 | Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/pirogue (retrieved 29 July 2009). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.