Cruzatte’s Fiddle

Daniel Slosberg represents v in his own widely acclaimed production for schools and other venues, A Musical Journey on the Lewis & Clark Trail. For more information, visit Dan’s Web site.

Dan’s playing and singing are featured below.

The journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition contain references to some thirty occasions when the men turned to song and dance for their own recreation, or to entertain and impress the Indian people they met.

The idea of celebrating a new round of seasons in the dead of winter must have excited great wonder among the Indians in the vicinity of Fort Mandan, but some of the men of the Corps of Discovery were delighted with the opportunity to share their Southern-style New Year’s festivities. So, at about nine in the morning on 1 January 1805, fifteen of them set off for the nearby Mandan village. They took with them, reported Sergeant John Ordway, “a fiddle & a Tambereen [tambourine] & a Sounden horn [sounding horn].”

The company’s baggage contained a supply of jews harps, ostensibly as gifts to young Indian men. These, along with the numerous percussion instruments that might have been improvised from the company’s kit of blacksmith tools, combined to make a spirited accompaniment to the men’s singing and dancing.

Cruzatte’s Fiddlin’

The principal catalyst for their musical diversions was undoubtedly Private Pierre Cruzatte, whose official duty was as a boatman, but who also played the fiddle. George Gibson, who specialized as a hunter and sign-language interpreter, played the fiddle too, on at least one occasion—at the party and dance the Wallulas held for the Corps on 19 October 1805.

Fiddlers like Pierre Cruzatte played popular dance tunes—most of them of unknown origin—by ear, and probably had comparatively limited repertoires. Violinists like Thomas Jefferson played, by note, the latest published works by famous composers, as well as those of the old masters. To call a violinist a fiddler was considered uncomplimentary, although some “gentlemen amateurs,” such as Jefferson, were at least somewhat acquainted with the popular idioms.

Very little is known of Pierre Cruzatte, who enlisted at St. Charles, Missouri, on 16 May 1804 as a boatman, or pilot. The son of a French father and an Omaha Indian mother, he had worked on the Lower Missouri River as a trader for the house of Chouteau in St. Louis, and was also fluent in sign-language, the lingua franca of the Western frontier.

“This Crusat is near Sighted and has the use of but one eye,” Clark explained on 12 August 1806—a few days after the unfortunate Creole had accidentally shot Captain Lewis in the buttocks. “He is an attentive industerous man,” Clark continued, “and one whome we both have placed the greatest Confidence in dureing the whole rout.”

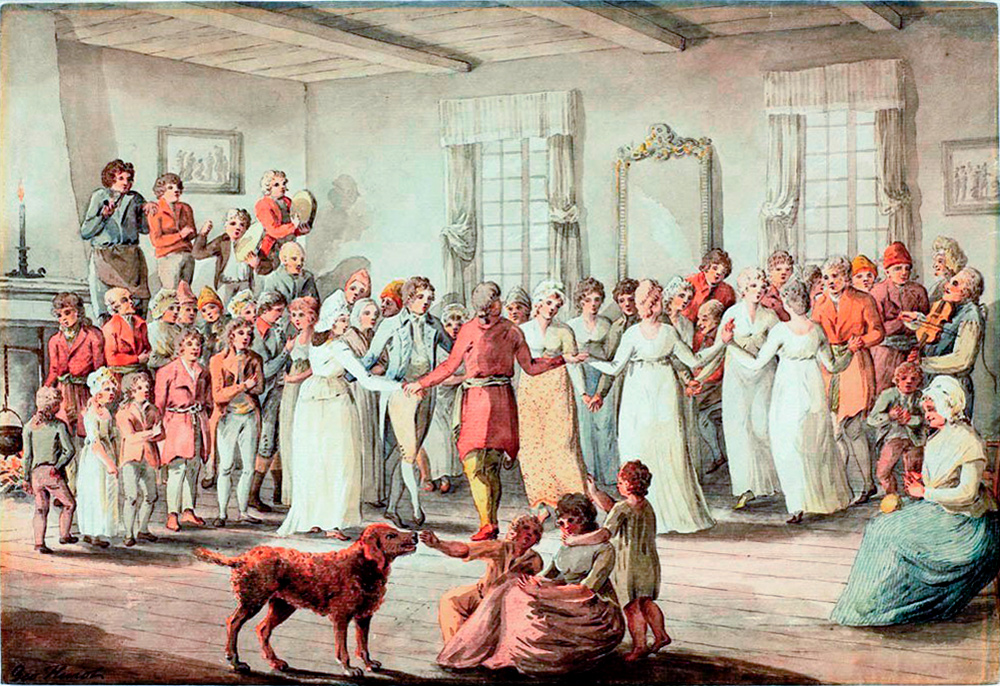

All of the Corps were duly appreciative of Cruzatte’s talent as a fiddle player, with which he embellished their rare hours of leisure as well as their diplomatic relations with many Indian tribes—until very late in the trip (see The Last Dance.). Back in June 1805 Clark had remarked that Cruzatte played the instrument “extreemly well.” Unfortunately, nothing else the captain could have said would tell us as much about the sound of his playing as the picture above. We don’t know whether the artist, George Heriot, knew anything about music or musical instruments, nor how accurately he recorded visual details, but his depiction of these two violinists corresponds with ample written evidence about performances of dance music around the turn of the nineteenth century.

Look closely at the fiddler in the detail on the left from Heriot’s Dance in the Chateau St. Louis. Notice that he holds his instrument almost vertically, bracing it against his collarbone. He holds it under his chin—against his collarbone— but not with his chin as does the violinist pictured at right. His left arm is close to his side, and he twists that hand around rather awkwardly to grasp the neck of the instrument and finger the strings. This means he cannot shift hand positions up and down the fingerboard without risk of dropping his instrument, but he can easily play tunes with narrow ranges that revolve closely around a tonal center, like “Yankee Doodle.” The most challenging pieces in Thomas Jefferson’s music library required shifting through as many as five positions. But then, the elder Jefferson claimed he had practiced no less than three hours every day for twelve years.

The chin rest, which prevents the player’s chin from dampening the resonance of the violin’s body, was invented in the 1820s. The neck of the fiddler’s instrument appears to be shorter than that of a modern violin, but since he doesn’t have to play extremely high notes, he has no need of longer strings.

During the early 19th century the violin gained a louder and more brilliant tone in response to the demands of larger concert halls and the rise of violin virtuosos such as Lewis and Clark’s younger contemporary, Nicolo Paganini (1782-1840). The bridge grew higher, the fingerboard tilted away from the body, and strings began to be made of new materials. Aside from the rare and expensive Amatis, Stradivaris, and Guarnieris of the 17th century, an “old” violin today has a history of only about a hundred years. Violins that have never been “improved” are scarce, and are of dubious value as true examples of older practices and tastes.[1]Toward the end of the twentieth century the electric violin emerged in the vernacular tradition. With the sound digitally synthesized, and modifiable to a player’s taste, the resonant hollow … Continue reading Even the highly prized instruments made by Amati, Stradivari, and Guarnieri back in the 17th century have been modernized—the bridge made higher, the fingerboard made longer and tilted upward, and a chin rest added.

Four Tunes

Fisher’s Hornpipe

Daniel Slosberg as Pierre Cruzatte plays one of the most popular tunes in the Lewis and Clark period

V’la l’bon vent

Daniel Slosberg as Pierre Cruzatte sings a French voyageur’s song.

Rose Tree

Gibson, a young Kentuckian, might have known “The Rose Tree,” which was among the standard popular tunes of the day. The song had apparently earned its place on the “charts” of popular music when it was heard in a little comic opera entitled The Poor Soldier, presented in Philadelphia in 1783, and known to have been a favorite of George Washington’s. To this day, the tune is fairly well known among “Old-Time” fiddlers in several slightly different versions.

Old French Hornpipe

Cruzatte, who was half French and half Omaha Indian, might have been better acquainted with traditional French tunes such as “Old French Hornpipe.”

Instruments They Didn’t Bring

There are several portable acoustic musical instruments that many people associate with the sound of old-time music, and that they suppose should be included in an instrumental ensemble that purports to evoke the sound of the music the men of the Corps of Discovery enjoyed on the trail. In the interest of factual relevance, while knowing we can never perfectly recapture either the sound or the spirit of their music-making, here are some answers to some obvious questions.

. . . a banjo?

Because the banjo did not belong to American popular culture during the era of Lewis and Clark. Writing of slave culture in his book, Notes on Virginia, Thomas Jefferson stated, “The instrument proper to them is the Banjar, which they brought hither from Africa.”[2]Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, ed. William Peden (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1954), 288n. Jefferson also averred that the banjar was the antecedent of the … Continue reading

The banjo evolved out of a West African long-necked string instrument, its body made of half a hollow gourd covered with animal hide. The banjo as we know it today became part of American popular culture about 1830, with the emergence of the minstrel show, a popular entertainment form consisting of parodies of Black culture, manners and music.

There is no evidence in the journals or elsewhere that York, Captain Clark’s personal slave, could play the “banjar.”

. . . a guitar?

The guitar did not hold the same position in 18th-century American popular culture as it came to occupy after 1850. One reason was that the violin ruled in both the vernacular and cultivated musical traditions, and guilds (“unions”).

The guitar originated in Spain during the early 16th century.[3]The word guitar is the Spanish cognate for the name of the ancient Greek plucked or strummed string instrument, the lyre-shaped cithara (pronounced either SITH-a-ra or KITH-a-ra). Around 1750 the five-course (five-string) form underwent a number of structural changes, including an increase to six courses. The first famous player of the new six-string guitar was the Spanish composer, Fernando Sor (1778-1839).[4]Sor, Lewis, and Clark were contemporaries, though it seems unlikely that they ever heard of one another.

In early eighteenth-century France, the guitar was mainly popular among the nobility, and is frequently seen in that context in the paintings of Antoine Watteau (1684-1721). In America, the guitar was the woman’s instrument of choice, primarily in the cultivated tradition. There were several guitars In Thomas Jefferson’s household at Monticello, belonging to his wife, daughter Polly, and granddaughters.[5]Helen Cripe, Thomas Jefferson and Music (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974), 47-48.

Eighteenth-century guitars were considerably smaller than modern guitars—sometimes but one-fourth as large—and used strings made of gut. Their sound was consequently much softer, sweeter, and less resonant than nineteenth and twentieth century instruments.

. . . a harmonica?

Because the harmonica was not invented until the mid-1820s, in Vienna, Austria. It was modeled after a Chinese wind instrument made of wood, with vibrating reeds, called a sheng, which was imported to Europe in 1777.

At first a novelty, and a children’s toy, the harmonica’s appeal spread slowly until it reached a peak of popularity in the mid-20th century, especially in blues and pop music. From the 1960s on, despite the musicians’ union’s refusal to acknowledge it as a musical instrument, it gained a permanent place in late 20th century American popular culture through the performances of Bob Dylan.

Folk and blues musicians and fans often speak of a harmonica as a “harp,” thus confusing it, in the minds of nearly everyone else, with a jews harp.

. . . a bass viol?

Although string bass instruments were less standardized then than now, and most types were smaller than today’s bass viol, any one of them still would have been too large to be conveniently carried on the expedition.

In the cultivated (“classical”) tradition during the 17th and 18th centuries, a bass instrument playing the bass notes, and a keyboard instrument to play the harmonies, were obligatory for most instrumental ensembles. The two together were called the basso continuo, or “continuous bass.” The bass instrument was normally bowed, not plucked or “slapped” as in today’s popular styles.

In the vernacular (“popular”) tradition, such as dance music, pictorial evidence suggests that the basso continuo was seldom present. In Protestant church music, however, a prominent, heavily-manned bass line was considered highly desirable. The American composer William Billings (1746-1800), whose hymns, anthems and psalms some of the men of the Corps might have known, preferred that half the singers in a choir be basses.

The bass viol, known also today as a bass fiddle, bull fiddle, string bass, double bass, or just bass,[6]Rhymes with base. The name is derived from the Italian word basso (pronounced BAH-so), meaning bottom. is nominally a member of the violin family, but in shape it retains some of the features of the pre-Renaissance viol family, such as the sloping upper body.

Recommended Reading

Robert R. Hunt, “Merry to the Fiddle: The Musical Amusement of the Lewis and Clark Party,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 14, No. 4 (November, 1988), lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol14no4.pdf#page=10.

Joseph Mussulman, “The Greatest Harmoney: ‘Meddicine Songs’ on the Lewis and Clark Trail,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 23, No. 2 (August, 1997), lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol23no4.pdf#page=2.

Notes

| ↑1 | Toward the end of the twentieth century the electric violin emerged in the vernacular tradition. With the sound digitally synthesized, and modifiable to a player’s taste, the resonant hollow body became unnecessary, and was replaced by a more durable solid body. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, ed. William Peden (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1954), 288n. Jefferson also averred that the banjar was the antecedent of the guitar, but that is false; they originated in two different, apparently isolated cultures. |

| ↑3 | The word guitar is the Spanish cognate for the name of the ancient Greek plucked or strummed string instrument, the lyre-shaped cithara (pronounced either SITH-a-ra or KITH-a-ra). |

| ↑4 | Sor, Lewis, and Clark were contemporaries, though it seems unlikely that they ever heard of one another. |

| ↑5 | Helen Cripe, Thomas Jefferson and Music (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974), 47-48. |

| ↑6 | Rhymes with base. The name is derived from the Italian word basso (pronounced BAH-so), meaning bottom. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.