Tobacco Leaves

Interpretation by John W. Fisher. Photo © 2010 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

A tightly rolled, twisted bundle of tobacco leaves (Nicotiana tabacum), called a carrot, was convenient for chewers. A bite was called a “plug.”

It is a remarkable fact that Meriwether Lewis‘s planning for the expedition resulted in a surplus of four essential commodities: lead for bullets and powder to fire them, ink to write with and paper to write on. It was equally significant, as far as most of the men were concerned, that they ran short of tobacco and whiskey.

In spite of the captains’ judicious rationing, the men drank the last of their supply of whiskey on 4 July 1805, and some of them–almost certainly including Meriwether Lewis–must have rued that day, not knowing how long it would be before they could down another snort, and perhaps fearful of the effects the deprivation would produce in their minds and bodies. Private Collins brewed a little beer from fermented camas bread–”which,” Clark explained, “by being frequently wet molded & Sowered &c.”—on their way down the Columbia (21 October 1805), and Clark pronounced it excellent, but evidently it wasn’t tried again, probably for lack of time.

Short Rations

From the Yellowstone River in late July 1806, William Clark ordered Sergeant Pryor and two privates to go on ahead to the Knife River Villages with the company’s horses, and then to proceed to a trading post on the Assinniboin River in Canada. There he was, among other duties, to purchase from trader Hugh Heney “such articles as we may stand in need of.” Pryor’s shopping list included pepper, sugar, coffee or tea, handkerchiefs, a hat for Sergeant Ordway, knives, flints, whiskey, and tobacco. Regrettably, the loss of all the horses in his charge prevented the detail from succeeding.

But later, on 6 September 1806, as the reunited Corps of Discovery was speeding down the Missouri River toward St. Louis, they met an outbound party of traders whose sympathetic leader gave them a gallon of whiskey, and after 429 uncomfortable and thirsty days their dry spell was over.

Actually, the lack of liquor was a violation of military regulations. In 1802 Congress had raised the statutory ration from half a gill to a full gill of rum, brandy or whiskey per man per day.[1]A “gill” is one-fourth of a pint, or four fluid ounces. By the modern standards of the American Medical Association and the National Safety Council, four ounces of whiskey results in a … Continue reading

Worse yet, for all but seven members of the company, had been the discovery that, as many alcoholic smokers learn, nicotine proves to be a primary addiction, and the longing for it is often harder to bear than the thirst for booze. The link between the two drugs was clear to Benjamin Rush, the nation’s leading physician and unofficial surgeon general of the U.S. at the time, and Lewis’s medical mentor during preparations for the expedition. Dr. Rush held the opinion that both smoking and chewing tobacco were unhealthy because they always led to drunkenness.

Tobacco Addiction

At Fort Mandan during the winter of 1804–05, the local Indians graciously offered the Corps some of their own fragrant “tobacco,” which Frederick Pursh was soon (1813) to name Nicotiana quadrivalvis.[2]The Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras had also gotten from the southwest, perhaps through intertribal trade over some period of time, the vegetables that were staples in their diet: squashes, pumpkins, … Continue reading The Indians of the Great Plains had possibly acquired the plant from the far West long before Europeans landed on the Atlantic seaboard. But it was not nearly as potent a drug as the domestic Virginia variety, Nicotiana tabacum. Sergeant Gass was to remark in his journal that the Indian tobacco was good enough for smoking, but not much of a chew, which was the preference of most of the users in the Corps. The depth of the chewers’ torment is reflected in the journals from time to time. Nicholas Biddle, who edited the first edition of the journals, was told that at Fort Clatsop some of them chopped up smokers’ pipe stems to suck out the nicotine residue. On Christmas morning, 1805, the captains made the dreary day a little more festive by distributing a few carrots of tobacco among the users (the seven non-users received new handkerchiefs). One way of stretching it was to mix it with the leaves and bark of the bearberry plant, or the bark of the wild crabapple or red willow, but they contained no nicotine whatsoever.[3]However, besides tobacco there are other members of the Solanaceae, or potato family, that do contain nicotine. The most notable are Atropa bella-donna (bella-donna of Europe), Datura stramonium … Continue reading

Upon departure from Fort Clatsop, the need for rationing was all the more urgent inasmuch as N. tabacum was extremely valuable for trade and diplomatic negotiations with the Indians. So Lewis had to cut off the men’s rations entirely, which condemned them to “suffer much for the want of it.” When Clark and his contingent arrived back at Camp Fortunate on the Beaverhead River in July of that year, the addicts didn’t even take time to unsaddle their horses before clawing at the cache where they had stored some on the way out.

Although no one in those days admitted as much, and historians still tend overlook the fact, N. tabacum was far more addictive than alcohol, and was more insidious because it didn’t obviously affect its users’ social behavior.[4]“It is worthy of remark,” Lewis noted at Fort Mandan, “that the recares [Arikaras] never use sperituous liquors. Mr. Tibeau [Pierre-Antoine Tabeau] informed me that on a certain … Continue reading Before the end of the nineteenth century most Plains Indians, except for a few senior traditionalists, had forgotten about their fragrant but comparatively mild tobacco. In fact, although Jefferson grew some N. quadrivalvis from seeds Lewis sent him, it is the only plant Lewis collected that is no longer found in its previous habitat.

Dogwood Bark Substitute

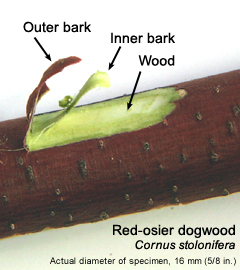

Cornus is a Latin name for dogwood; sericea refers to silky referring to the pubescence of the leaves. The species is found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, but our plant was long known as Cornus stolonifera whose name means having stolons, or shoots that grow along the ground. Osier is a French word meaning “willow bed.” An alternate denomination is Cornus sericea, the latter meaning “silky.” Red osier dogwood has been called kinnikinnick, too, owing to the use of its inner bark in smoking mixtures. All parts of the red osier dogwood can be toxic to humans.

Indeed, gathering and processing enough of the inner bark of the dogwood, chokecherry, or alder would be a tedious job, and it may have been that tedium, as much as the result, which made the smoking mixture personally and spiritually potent. Ponder the proto-scientific experiments that resulted in the discovery of which part of which plants, out of thousands upon thousands of different species, would help to improve the taste of the smoke of the leaf of the bearberry.

On 26 March 1806, three days after leaving Fort Clatsop, with their other trade goods reduced to a mere handful, Lewis remarked that their supply of tobacco was down to three carrots, or twists, and so he had cut off the mens’ rations. The chewers were obliged to substitute the Oregon crabapple (Malus fusca), while the smokers made do with the inner bark of the red-osier dogwood (see sidebar) or else straight sacacommis. None of these contained any nicotine, but the first was sufficiently unpleasant to the taste—”it is very bitter and they assure me they find it a good Substitute for tobacco,”—and the other two were sufficiently aromatic, to suitably serve as placebos.

Bearberry Substitute

Bearberry

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi

© 2007 by Walter Siegmund. Permission granted via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Hanging from a rafter in the captains’ quarters of the reconstructed Fort Clatsop is a bunch of dried branches of a widespread, durable, useful, and attractive member of the heath family of plants.[5]he heath family is known by students of botany as the Ericaceae (eri-CAY-see-ay, meaning “evergreen shrubs”). Consisting of about 4,000 species, Ericaceae comprise the largest family of … Continue reading

Dried Bearberry Leaves

© 2014 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Ever since their arrival at the mouth of the Columbia River, almost daily rains had drenched the men, soaked their baggage, and spoiled their fresh meat. The urgency of erecting a common shelter overrode nearly every other need except, for all but seven of the men, some means of stretching their dwindling supply of Turkish tobacco. On the morning of 2 December 1805, deeming it advisable to spare some hands from the construction project, Clark “dispatched two men to the open lands near the Ocian for Sackacome, which we make use of to mix with our tobacco to Smoke, which has an agreeable flavour.”

The captains had been introduced to the plant at Fort Mandan on 28 February 1805 by two men bearing letters and gifts from Hugh Heney (or Hené), a trader with the North West Company at Fort Assiniboin, 150 miles to the north. Recalling that gift on 25 January 1806, Lewis identified the local west coast variety as “the plant called by the Canadin Engages [Canadian engagés, or hired hands] of the N. W. sac a commis.”

Lewis’s Bearberry Specimen

Lewis sent a specimen back to President Jefferson on the barge that spring, perhaps the very one Heney had sent him. It is item No. 33 in the list prepared by John Vaughan of the American Philosophical Society, where Jefferson sent Lewis’s specimens. In Lewis’s words, it was “an evergreen plant which grows usually in the open plains, the natives smoke its leaves mixed with Tobacco; called by the French engages Sacacommé. Obtained at Fort Mandan.”[6]Moulton, 3:464. This information probably was taken from Lewis’ seemingly incomplete written report about his collections. During the winter of 1804-1805 Lewis drafted “A List of … Continue reading

It cannot be said that Lewis discovered sacacommis, for the Connecticut Yankee Jonathan Carver (1710–1780), who explored the upper Mississippi Valley in the late 1760s, reported that “a weed that grows near the great lakes, in rocky places, they use in the summer season. It is called by the Indians Segockiniac, and creeps like a vine on the ground, sometimes extending to eight or ten feet. . . . These leaves, dried and powdered, they likewise mix with their tobacco.”[7]Jonathan Carver, Travels Through the Interior Parts of North-American, in the years 1766, 1767, and 1768 (London: 1778), p. 31. Carver was a Connecticut gentleman, shoemaker, soldier, self-taught … Continue reading Carver did not bring back any specimens.

A typical formula for a smoking mixture in the Pacific Northwest might consist of equal parts of dried bearberry leaf; the leaf of the Labrador tea (Ledum glandulosum), the inner bark of red osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), wormwood leaf (Artemisia frigida); the inner bark of the chokecherry (Prunus virginiana, var. melanocarpa), and the inner bark of any one of several species of alder (Alnus spp.).[8]Terry Willard, Edible and Medicinal Plants of the Rocky Mountains and Neighbouring Territories (Calgary, Alberta: Wild Rose College of Natural Healing, 1992), 164–65. In the Great Lakes region the … Continue reading

Native Practices

Nicotiana tabacum was widely and commonly used by the English and early American colonists, but farther inland, where conditions were comparatively dry, several different species were grown. Many Indian groups on the Great Plains used Nicotiana rustica, or “Aztec tobacco.” Indians on the upper Missouri grew Nicotiana quadrivalvis var.[variety] quadrivalis, while in coastal Oregon and Washington the common tobacco was Nicotiana quadrivalvis var. multivalvis. All of those varieties of Nicotiana quadrivalis have been extirpated. To the south, mainly in the Great Basin and to lesser degrees in the Southwest and California, the Indians still grow Nicotiana quadrivalis var. bigelovii.

Tobacco is still a central ingredient in Indian cultural traditions and sacred rituals, but the price of addiction to the commercial Turkish species—diabetes, emphysema, heart problems and cancers—has clearly become too high to tolerate any longer. According to statistics published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4.1 Indians out of every 100,000 in the Southwest die from lung cancer caused by smoking; the rate among Indians in Montana and Wyoming is seven times higher, at 28.5 deaths per 100,000. Tribal health-care officials throughout the country currently are participating in the Indian Health Board’s In-Care Network program called “Beyond the Pipe,” which aims toward replacing Marlboros, Winstons, and the like with some of the old ceremonial mixtures—blends of wild herbs such as bearberry, mullein, red willow bark, osha root, and yerba santa.

Meriwether Lewis wrote on 8 January 1806, about the neighbors’ fondness for smoking:

The Clatsops Chinnooks and others inhabiting the coast and country in this neighbourhood, are excessively fond of smoking tobacco. In the act of smoking they appear to swallow it as they draw it from the pipe, and for many draughts together you will not perceive the smoke which they take from the pipe. In the same manner also they inhale it in their lungs untill they become surcharged with this vapour when they puff it out to a great distance through their nostils and mouth; I have no doubt the smoke of the tobacco in this manner becomes much more intoxicating and that they do possess themselves of all it’s virtues in their fullest extent; they freequently give us sounding proofs of it’s creating a dismorallity of order in the abdomen, nor are those light matters thought indelicate in either sex, but all take the liberty of obeying the dictates of nature without reserve.

Those “sounding proofs” must have greatly amused the American visitors–almost any 12-year-old boy will happily demonstrate the consequence of swallowing lots of air. In fact, when the use of tobacco was introduced into Europe–for its “medicinal” properties, believe it or not–the verb that described its consumption was “to drink,” the present one, “to smoke” arriving late in the 17th century.

Important: The ingestion of some plants can be harmful or even fatal. Experimentation and/or self-medication with wild foods and medicines without advice from a physician or other qualified authority is not recommended.

Notes

| ↑1 | A “gill” is one-fourth of a pint, or four fluid ounces. By the modern standards of the American Medical Association and the National Safety Council, four ounces of whiskey results in a blood alcohol level of 0.10 percent, at which point the consumer is legally intoxicated, and is prohibited from operating a motor vehicle. See on this site Alcohol Rations by Robert R. Hunt. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras had also gotten from the southwest, perhaps through intertribal trade over some period of time, the vegetables that were staples in their diet: squashes, pumpkins, watermelons, and many varieties of beans and corn. See Melvin R. Gilmore, Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region (1919; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1977), p. 7. |

| ↑3 | However, besides tobacco there are other members of the Solanaceae, or potato family, that do contain nicotine. The most notable are Atropa bella-donna (bella-donna of Europe), Datura stramonium (jimsonweed, a plant of the Americas), and Solanum tuberosum (potato, a South American species). Small amounts are reported in such plants as celery, papaya, coca, English walnut and even non-flowering plants like the club-moss Lycopodium clavatum (running ground-moss) found in the eastern United States and in the Pacific Northwest. —James L. Reveal. |

| ↑4 | “It is worthy of remark,” Lewis noted at Fort Mandan, “that the recares [Arikaras] never use sperituous liquors. Mr. Tibeau [Pierre-Antoine Tabeau] informed me that on a certain occasion he offered one of their considerate men a dram of sperits, telling him it’s virtues— The other replyed that he had been informed of it’s effects and did not like to make himself a fool unless he was paid to do so— that if Mr. T. wished to laugh at him & would give him a knife or breech-cloth or something that kind he would take a glass but not otherwise.” Lewis’s natural history notes, Codex R. Reuben Gold Thwaites, Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804–06 (7 vols. and supplement, New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1905), 6:150. “Fort Mandan Miscellany” in Moulton, Journals, 3:460–61. A biographical note on Pierre Tabeau is in Moulton, 3:155–56n. |

| ↑5 | he heath family is known by students of botany as the Ericaceae (eri-CAY-see-ay, meaning “evergreen shrubs”). Consisting of about 4,000 species, Ericaceae comprise the largest family of the order Ericales, which includes such food plants as blueberries and cranberries. |

| ↑6 | Moulton, 3:464. This information probably was taken from Lewis’ seemingly incomplete written report about his collections. During the winter of 1804-1805 Lewis drafted “A List of specimines of plants collected by me on the Mississippi and Missouri rivers” but the extant copy lists plant specimens 1 through 32 and 100 through 108. The first 32 numbered specimens gathered by Lewis are also missing. |

| ↑7 | Jonathan Carver, Travels Through the Interior Parts of North-American, in the years 1766, 1767, and 1768 (London: 1778), p. 31. Carver was a Connecticut gentleman, shoemaker, soldier, self-taught surveyor and cartographer, traveler and bigamist. He held a deep conviction, shared by few others in his day, that the Mississippi River would eventually become a North American Nile or Volga, and dreamed of exploring its upper reaches. In 1766 a similarly star-crossed visionary, Major Robert Rogers, hired him to explore a portion of the territory Great Britain had gained from its victory in the French and Indian War, namely that west of Michilimackinac, a major fur-trade post at the straits that separate Lake Huron from Lake Michigan. Carver was to record its geography, describe and count its Indians, and inventory the remains of French trading posts. Rogers also dreamed of finding the Great River of the West. Rogers, beset by political misfortunes, was unable to pay Carver, and he had to abandon his expedition. In 1769 he sailed to London, hoping through appeals to the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations to recoup his personal losses and resume his travels in North America. Failing in that, in 1778 he finally published his journal, which instantly became a bestseller, rocketing through some 32 printings in nine years. But its success was short-lived, for the author was accused of plagiarism, and of perpetrating a hoax. Penniless, Carver died of starvation in 1780. Not until the early 1900s was it discovered that, insofar as the charges were ever true, the guilt lay with Carver’s unscrupulous editor, who evidently had felt the explorer’s original journals needed a little extra color. Nevertheless, Carver’s Travels may have further stimulated Thomas Jefferson‘s long-held ambition to sponsor an expedition to the West. See http://bell.lib.umn.edu/hennepin/carver.html/ “The Adventures of Jonathan Carver,” by Ann K.D. Myers of the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota. Carver noted that the Chippewas mixed red-osier dogwood bark with their tobacco in wintertime, and harvested sumac bark for the same purpose at the end of September. He concluded: “By these three succedaneums the pipes of the Indians are well supplied through every season of the year; and as they are great smoakers, they are very careful in properly gathering and preparing them.” Ibid., p. 32. |

| ↑8 | Terry Willard, Edible and Medicinal Plants of the Rocky Mountains and Neighbouring Territories (Calgary, Alberta: Wild Rose College of Natural Healing, 1992), 164–65. In the Great Lakes region the Labrador tea is Ledum groenlandicum, from Ledum, a Greek word for “evergreen shrub,” and groenlandicum, for Greenland, which is east of Labrador across the North Atlantic. Chokecherry is Prunus virginiana, literally, “Virginia plum,” and the var. virginiana is the common form in Eastern North America whereas the var. melanocarpa (Greek, meaning “black fruit”) occurs in the American West including the Great Plain. The alder of the Great Lakes region is Alnus viridis subsp. crispa (alnus is the Latin name for alder, viridis is Latin for green, and crispa is Latin for crooked). In the Pacific Northwest, the common alders are the speckled alder (Alnus incana; from the Latin incanus for gray or hoary), white alder (Alnus rhombifolia; from the Latin rhombus for a spinning-top but botanically used to mean twisting or turning as in the wind, and folium, for leaf), and red alder (Alnus rubra; Latin for red). Any one of these species could have been used by Native Americans and travelers alike.(Indian legend relates that Coyote, the notorious trickster and fool, couldn’t hit a target with his bow-and-arrow because he made his arrows of the alder’s crooked branches.) |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.